Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

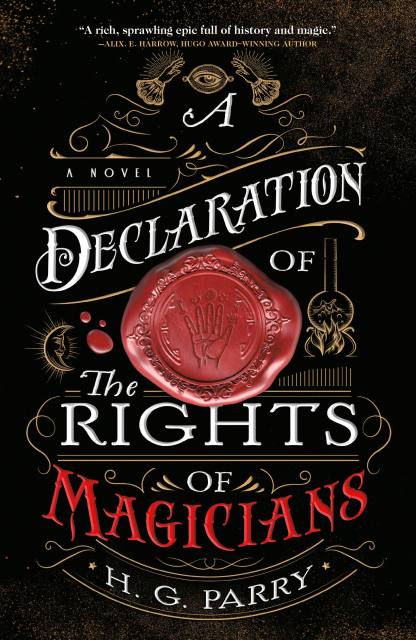

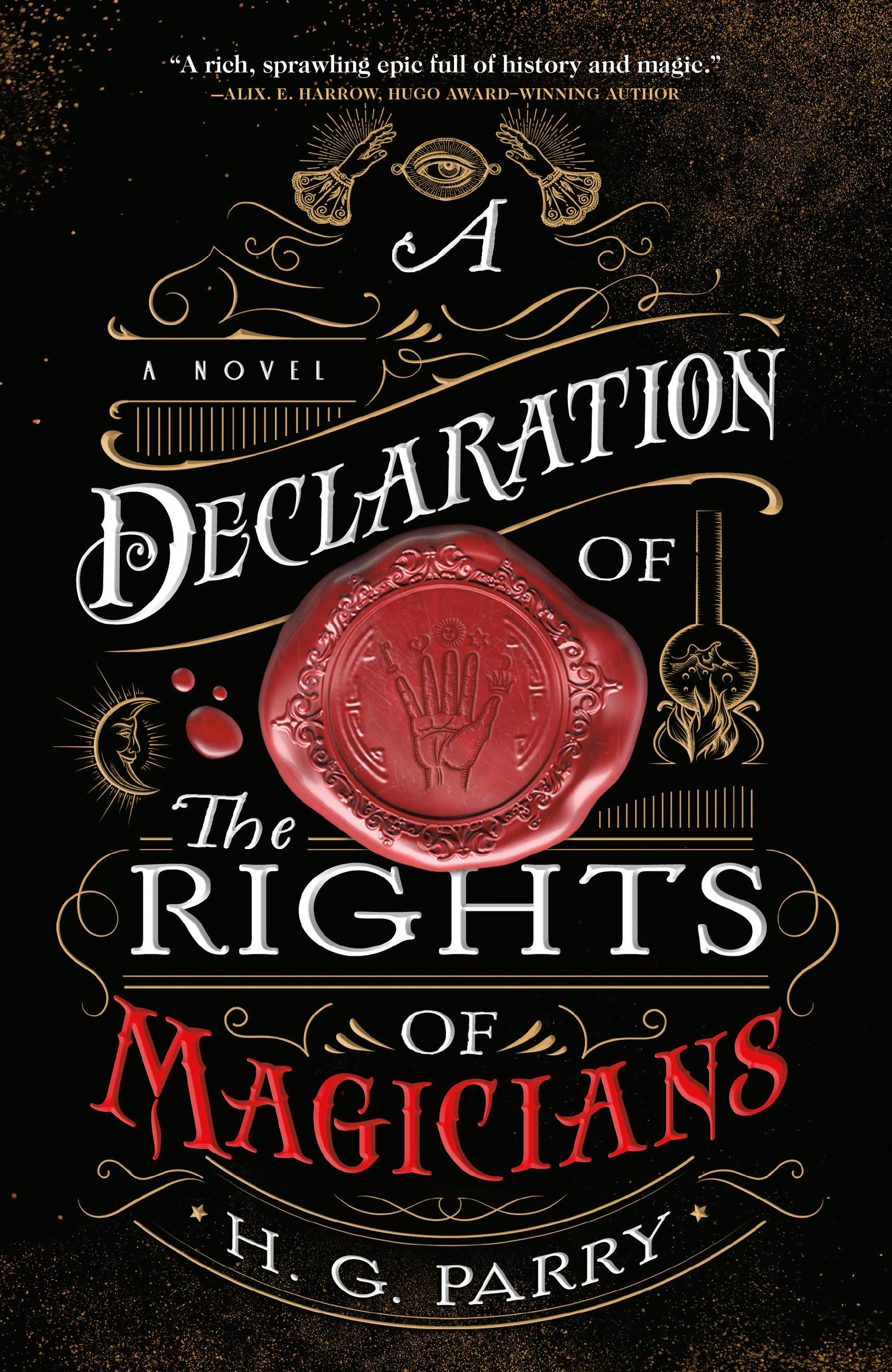

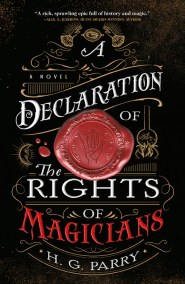

A Declaration of the Rights of Magicians

A Novel

Contributors

By H. G. Parry

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 23, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A sweeping tale of revolution and wonder in a world not quite like our own, A Declaration of the Rights of Magicians is a genre-defying story of magic, war, and the struggle for freedom in the early modern world.

It is the Age of Enlightenment — of new and magical political movements, from the necromancer Robespierre calling for a revolution in France, to the weather mage Toussaint L'Ouverture leading the slaves of Haiti in their fight for freedom, to the bold new Prime Minister William Pitt weighing the legalization of magic amongst commoners in Britain and abolition throughout its colonies overseas.

But amidst all of the upheaval of the early modern world, there is an unknown force inciting all of human civilization into violent conflict. And it will require the combined efforts of revolutionaries, magicians, and abolitionists to unmask this hidden enemy before the whole world falls to darkness and chaos.

Praise for A Declaration of the Rights of Magicians:

"A rich, sprawling epic full of history and magic, Declaration is Jonathan Strange with international politics and vampires. I loved it."―Alix E. Harrow, Hugo Award-winning author

"A witty, riveting historical fantasy…Parry has a historian's eye for period detail and weaves real figures from history-including Robespierre and Toussaint L'Ouverture-throughout her poetic tale of justice, liberation, and dark magic. This is a knockout."―Publishers Weekly (starred review)

The Shadow Histories

A Declaration of the Rights of Magicians

A Radical Act of Free Magic

For more from H. G. Parry, check out The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep.

It is the Age of Enlightenment — of new and magical political movements, from the necromancer Robespierre calling for a revolution in France, to the weather mage Toussaint L'Ouverture leading the slaves of Haiti in their fight for freedom, to the bold new Prime Minister William Pitt weighing the legalization of magic amongst commoners in Britain and abolition throughout its colonies overseas.

But amidst all of the upheaval of the early modern world, there is an unknown force inciting all of human civilization into violent conflict. And it will require the combined efforts of revolutionaries, magicians, and abolitionists to unmask this hidden enemy before the whole world falls to darkness and chaos.

Praise for A Declaration of the Rights of Magicians:

"A rich, sprawling epic full of history and magic, Declaration is Jonathan Strange with international politics and vampires. I loved it."―Alix E. Harrow, Hugo Award-winning author

"A witty, riveting historical fantasy…Parry has a historian's eye for period detail and weaves real figures from history-including Robespierre and Toussaint L'Ouverture-throughout her poetic tale of justice, liberation, and dark magic. This is a knockout."―Publishers Weekly (starred review)

The Shadow Histories

A Declaration of the Rights of Magicians

A Radical Act of Free Magic

For more from H. G. Parry, check out The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep.

Genre:

-

"A rich, sprawling epic full of history and magic, Declaration is Jonathan Strange with international politics and vampires. I loved it."Alix E. Harrow, author of The Ten Thousand Doors of January

-

"A witty, riveting historical fantasy....Parry has a historian's eye for period detail and weaves real figures from history-including Robespierre and Toussaint L'Ouverture-throughout her poetic tale of justice, liberation, and dark magic. This is a knockout."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Impeccably researched and epically written, this novel is a stellar start to what promises to be a grand new fantasy series."Booklist (starred review)

-

""I absolutely loved it. It held my attention from the beginning and throughout. It's a beautiful tapestry of words, a combination of carefully observed and researched history and a well-thought-out and fascinating system of magic. An absolute delight to read; splendid and fluid, with beautiful and complex use of language."Genevieve Cogman, author of The Invisible Library

-

"Fans of Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell will be enchanted by this sprawling epic of revolution and dark magic."Locus

-

"It's no simple task to wrangle fifteen years of tumult in a few hundred pages, but Parry manages it with a deft hand. Her alternate history puts a human face on the titans of the past, while weaving in supernatural elements that add a whole new dimension. I stayed up well past my bedtime to find out what happens next."Marie Brennan, author of the Memoirs of Lady Trent series

-

"Impressively intricate; fans of the magic-and-history of Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell will be delighted."Alexandra Rowland, author of A Conspiracy of Truths

-

Praise for H. G. Parry:

"A star-studded literary tour and a tangled mystery and a reflection on reading itself; it's a pure delight." --Alix E. Harrow, bestselling author of The Ten Thousand Doors of January on The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

"Many have tried and some have succeeded in writing mashups with famed literary characters, but Parry knocks it out of the park... Just plain wonderful." --Kirkus (starred review) on The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

"Fun, witty, and full of insights about the powerful effect of stories on our lives, this book is highly recommended." --Booklist (starred review) on The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

"H.G. Parry's ambitious debut novel is a delight of magic and literature, love and adventure. With vibrant characters and a passion for story that shines through every word, this engaging read establishes Parry as a writer to watch." --Kat Howard, author of The Unkindness of Ghosts on The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

"A delightful blend of adventure and mystery and marvel, a story in which the fantastical becomes real. This beautifully-written novel is an exploration of the power fiction wields -- the power to inform and to change, even to endanger, our everyday world." -- Louisa Morgan, author of A Secret History of Witches on The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

"A rollicking adventure that thrills like Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere mashed up with Penny Dreadful in the best post-modern way. Equal parts sibling rivalry, crackling mystery, and Dickensian battle royale, it'll be one of your most fun reads this year." --Mike Chen, author of Here and Now and Then

"A joyous adventure through all the tales you've ever loved. Funny, charming, clever and heartfelt, you're absolutely going to adore The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep." --Tasha Suri, author of Empire of Sand

- On Sale

- Jun 23, 2020

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- Redhook

- ISBN-13

- 9780316459099

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use