Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

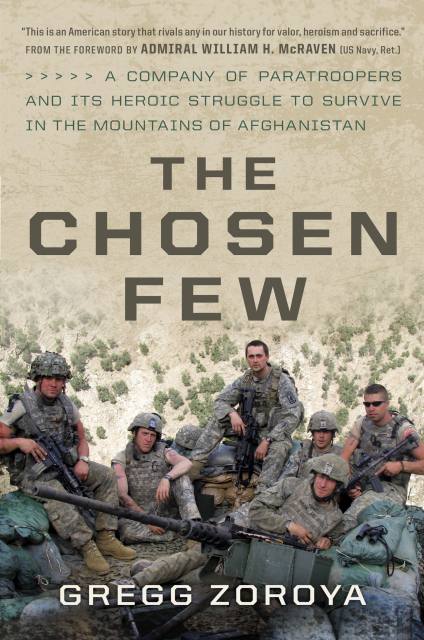

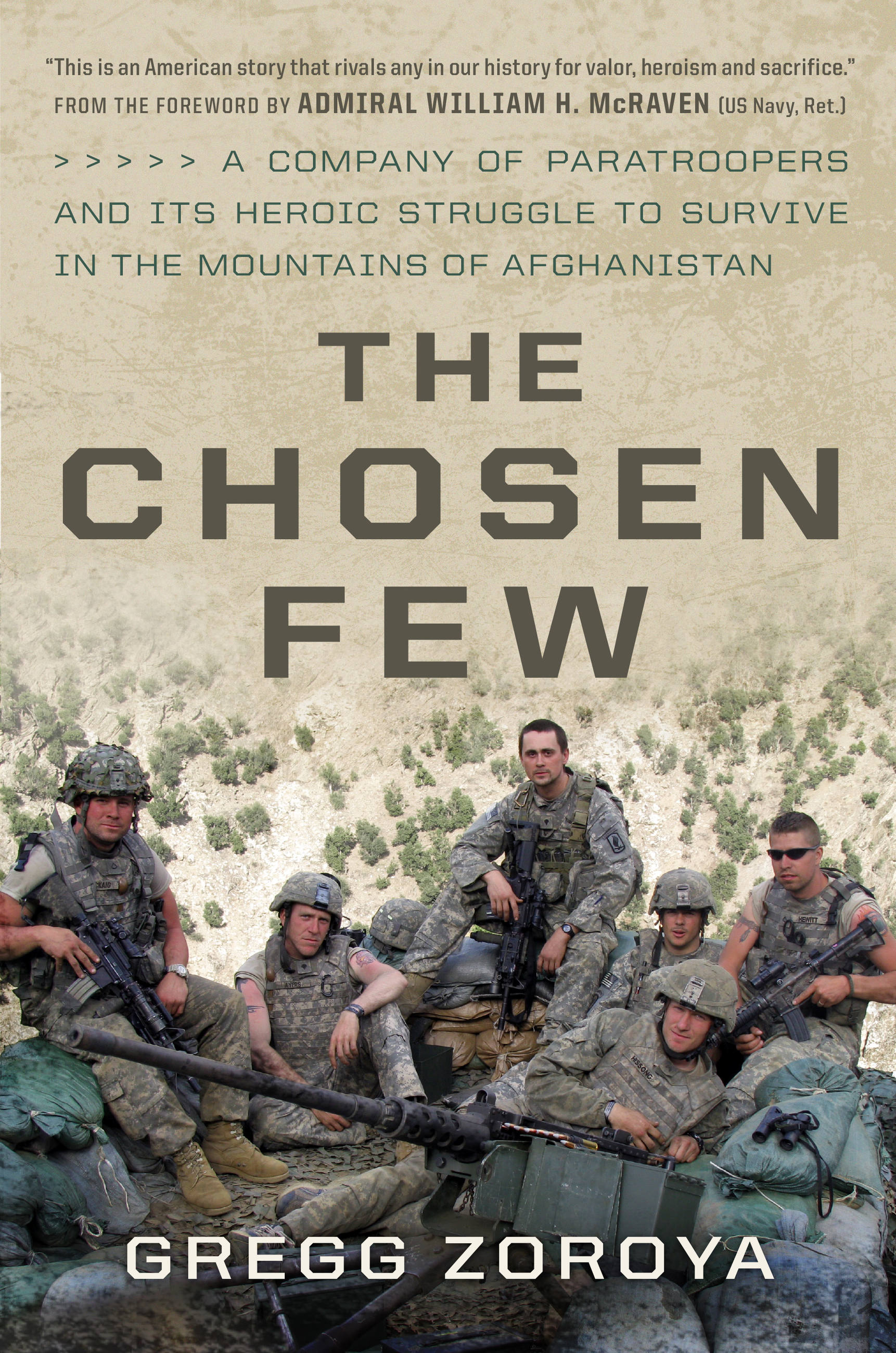

The Chosen Few

A Company of Paratroopers and Its Heroic Struggle to Survive in the Mountains of Afghanistan

Contributors

By Gregg Zoroya

Foreword by Admiral William H. McRaven

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 14, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A single company of US paratroopers–calling themselves the “Chosen Few”–arrived in eastern Afghanistan in late 2007 hoping to win the hearts and minds of the remote mountain people and extend the Afghan government’s reach into this wilderness. Instead, they spent the next fifteen months in a desperate struggle, living under almost continuous attack, forced into a slow and grinding withdrawal, and always outnumbered by Taliban fighters descending on them from all sides.

Month after month, rocket-propelled grenades, rockets, and machine-gun fire poured down on the isolated and exposed paratroopers as America’s focus and military resources shifted to Iraq. Just weeks before the paratroopers were to go home, they faced their last–and toughest–fight. Near the village of Wanat in Nuristan province, an estimated three hundred enemy fighters surrounded about fifty of the Chosen Few and others defending a partially finished combat base. Nine died and more than two dozen were wounded that day in July 2008, making it arguably the bloodiest battle of the war in Afghanistan.

The Chosen Few would return home tempered by war. Two among them would receive the Medal of Honor. All of them would be forever changed.

-

"Historians and journalist have penned many books about what Tom Brokaw dubbed 'the greatest generation' those men who came from simple lives to the battlefields of World War II and left a sense that those kinds of men no longer walk among us. Zoroya makes the case that that assumption is entirely incorrect, that we indeed have a new generation of heroic men who fight to overcome the overwhelming odds that are thrown against them."My Big Honkin Blog

-

"A searing account of war in Afghanistan...A remarkable story, whose telling raises myriad questions without resorting to polemics. It is unlikely that those who read it will ever utter the phrase, 'Thank you for your service,' quite the same way again...A gripping, exhaustively reported account of modern warfare...[Zoroya] cuts through the fog of war...Zoroya delivers the adrenaline of combat right to the reader's easy chair. His prose is direct and clear, and never upstages the action. He also brings the warriors to life, chronicling their trials and triumphs."USA Today

-

"The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are now producing their own volumes, and this is one of the better ones...Well-researched...The book does an excellent job of telling the entire story of the action...As one of the most highly decorated units in Army history, these men, many of them from broken families and rough backgrounds, are worthy successors to Band of Brothers from previous generations of American fighting men."New York Journal of Books

-

"Riveting and heart-rending...Highly recommended for both personal and public library collections."Midwest Book Review

-

"The gripping, often heartbreaking story of Chosen Company's time in the Waygal Valley...In a style reminiscent of Stephen Ambrose's Band of Brothers, Zoroya takes readers beyond the blood and sweat of close combat and into the hearts and minds of the soldiers themselves. The result is an intensely personal and heart-wrenching tale of courage, love, and loss...a vivid portrait of America's war in Afghanistan...brutally honest in the telling, in a way that will affect readers deeply...The Chosen Few is an exceptional book...as revealing as it is enthralling. For military readers, The Chosen Few is a 'must read'; few books are as insightful, especially with respect to the character, courage, and commitment of those fighting for the future of Afghanistan. For readers with preconceived notions of what it means to engage in the 'forever war,' this book is a necessary addition to the bookshelf."Military Review

-

"A vivid military story [that] needed telling."Midwest Book Review

-

"[Zoroya] has given life to Chosen Company's story. His book...offers a personal look at what the Army soldiers endured in Afghanistan's remote Waigal Valley."West Central Tribune

-

"Reveal[s] much about the chaos of close combat and the brotherhood of men under fire."Military Officer

-

"Thoroughly researched...As the war in Afghanistan enters its 17th year, The Chosen Few is an admirable reminder of the brutality at the front."Military Periscope

-

"Zoroya, like so many great authors in the past, perfectly describes the fighting spirit of America's warriors...Zoroya pulls the reader in...The combat descriptions, as told to Zoroya by the men who experienced it, are gripping...Zoroya's writing is magnificent and powerful...A refreshing change from some of the books on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan is that Zoroya is not all rah rah U.S.A. He subtly points out the mistakes and deficiencies of American commanders...A gripping and enduring tribute to the men of the 'Chosen Few.'"Collected Miscellany

- On Sale

- Feb 14, 2017

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306824845

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use