Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

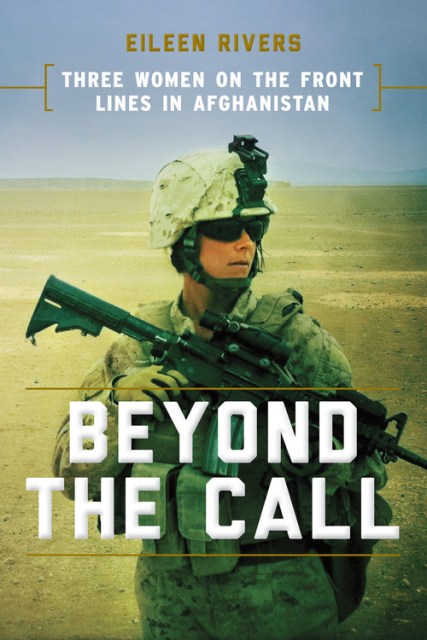

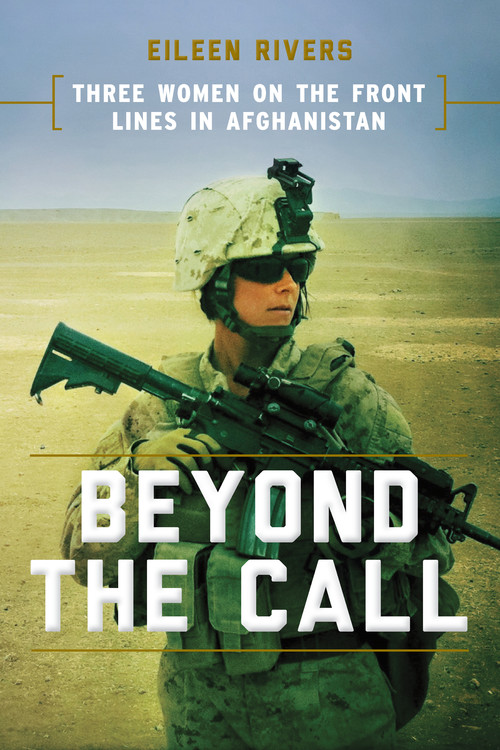

Beyond the Call

Three Women on the Front Lines in Afghanistan

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

They marched under the heat with 40-pound rucksacks on their backs. They fired weapons out of the windows of military vehicles, defending their units in deadly battles. And they did things that their male counterparts could never do–gather intelligence on the Taliban from the women of Afghanistan. As females they could circumvent Muslim traditions and cultivate relationships with Afghan women who were bound by tradition not to speak with American military men. And their work in local villages helped empower Afghan women, providing them with the education and financial tools necessary to rebuild their nation–and the courage to push back against the insurgency that wanted to destroy it. For the women warriors of the military’s Female Engagement Teams (FET) it was dangerous, courageous, and sometimes heartbreaking work.

Beyond the Call follows the groundbreaking journeys of three women as they first fight military brass and culture and then enemy fire and tradition. And like the men with whom they served, their battles were not over when they returned home.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306903076

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use