Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

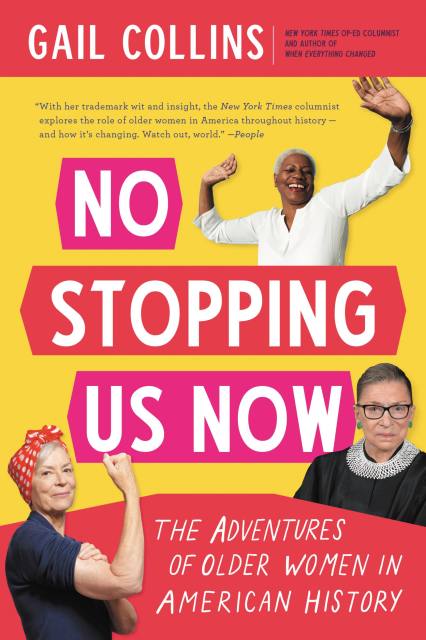

No Stopping Us Now

The Adventures of Older Women in American History

Contributors

By Gail Collins

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The beloved New York Times columnist "inspires women to embrace aging and look at it with a new sense of hope" in this lively, fascinating, eye-opening look at women and aging in America (Parade Magazine).

"You're not getting older, you're getting better," or so promised the famous 1970's ad — for women's hair dye. Americans have always had a complicated relationship with aging: embrace it, deny it, defer it — and women have been on the front lines of the battle, willingly or not.

In her lively social history of American women and aging, acclaimed New York Times columnist Gail Collins illustrates the ways in which age is an arbitrary concept that has swung back and forth over the centuries. From Plymouth Rock (when a woman was considered marriageable if "civil and under fifty years of age"), to a few generations later, when they were quietly retired to elderdom once they had passed the optimum age for reproduction, to recent decades when freedom from striving in the workplace and caretaking at home is often celebrated, to the first female nominee for president, American attitudes towards age have been a moving target. Gail Collins gives women reason to expect the best of their golden years.

"You're not getting older, you're getting better," or so promised the famous 1970's ad — for women's hair dye. Americans have always had a complicated relationship with aging: embrace it, deny it, defer it — and women have been on the front lines of the battle, willingly or not.

In her lively social history of American women and aging, acclaimed New York Times columnist Gail Collins illustrates the ways in which age is an arbitrary concept that has swung back and forth over the centuries. From Plymouth Rock (when a woman was considered marriageable if "civil and under fifty years of age"), to a few generations later, when they were quietly retired to elderdom once they had passed the optimum age for reproduction, to recent decades when freedom from striving in the workplace and caretaking at home is often celebrated, to the first female nominee for president, American attitudes towards age have been a moving target. Gail Collins gives women reason to expect the best of their golden years.

Genre:

-

"A deeply researched, entertaining book . . . [Collins] brings a reporter's eye to the facts and anecdotes, and never without humor."New York Times

-

"Collins . . . is a cheerful companion through the decades."Washington Post

-

"An eye-opening guide to our shifting attitudes about aging."New York Times

-

"Known for the punch of her columns, Collins sprinkles conversational asides throughout to keep this hike through the decades spry. . . . Former New Jersey Rep. Millicent Fenwick . . . is just one of the many fascinating, unstoppable exemplars Collins manages to squeeze into this tightly laced historical corset."Heller McAlpin, NPR

-

"A lively celebration of women's potential."Kirkus

-

"Collins continues her exploration of women's history with this breezy look at the position of older women in American society. This is a diverting and certainly interesting and valuable read."Booklist

-

"A lively and well-researched compendium. . . . This enjoyable and informative historical survey will delight Collins's fans and bring in some new ones."Publishers Weekly

-

Praise for When Everything Changed:Glenn C. Altschuler, NPR.com

"Splendid...Collins is a masterful storyteller." -

"Did feminism fail? Gail Collins's smart, thorough, often droll and extremely readable account of women's recent history in America not only answers this question brilliantly, but also poses new ones about the past and the present."Amy Bloom, The New York Times Book Review

-

"Riveting and remarkably thorough in its account of this tumultuous period."Rasha Madkour, Los Angeles Times

-

"Compulsively readable."Chris Vognar, Dallas Morning News

-

"Gail Collins has an unflaggingly intelligent conversational style that gives this book a personal and authoritative tone all at once."Cathleen Schine, The New York Review of Books

-

"Exhilarating, accessible, and inspiring."Katha Pollitt, Slate.com

-

"Gail Collins is such a delicious writer, it's easy to forget the scope of her scholarship in this remarkable look at women's progress."People

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316286497

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use