Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

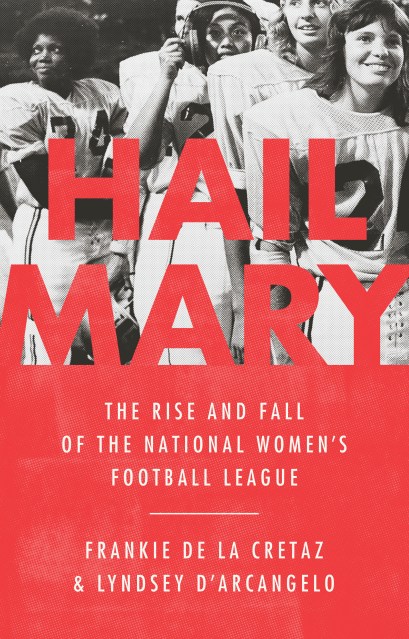

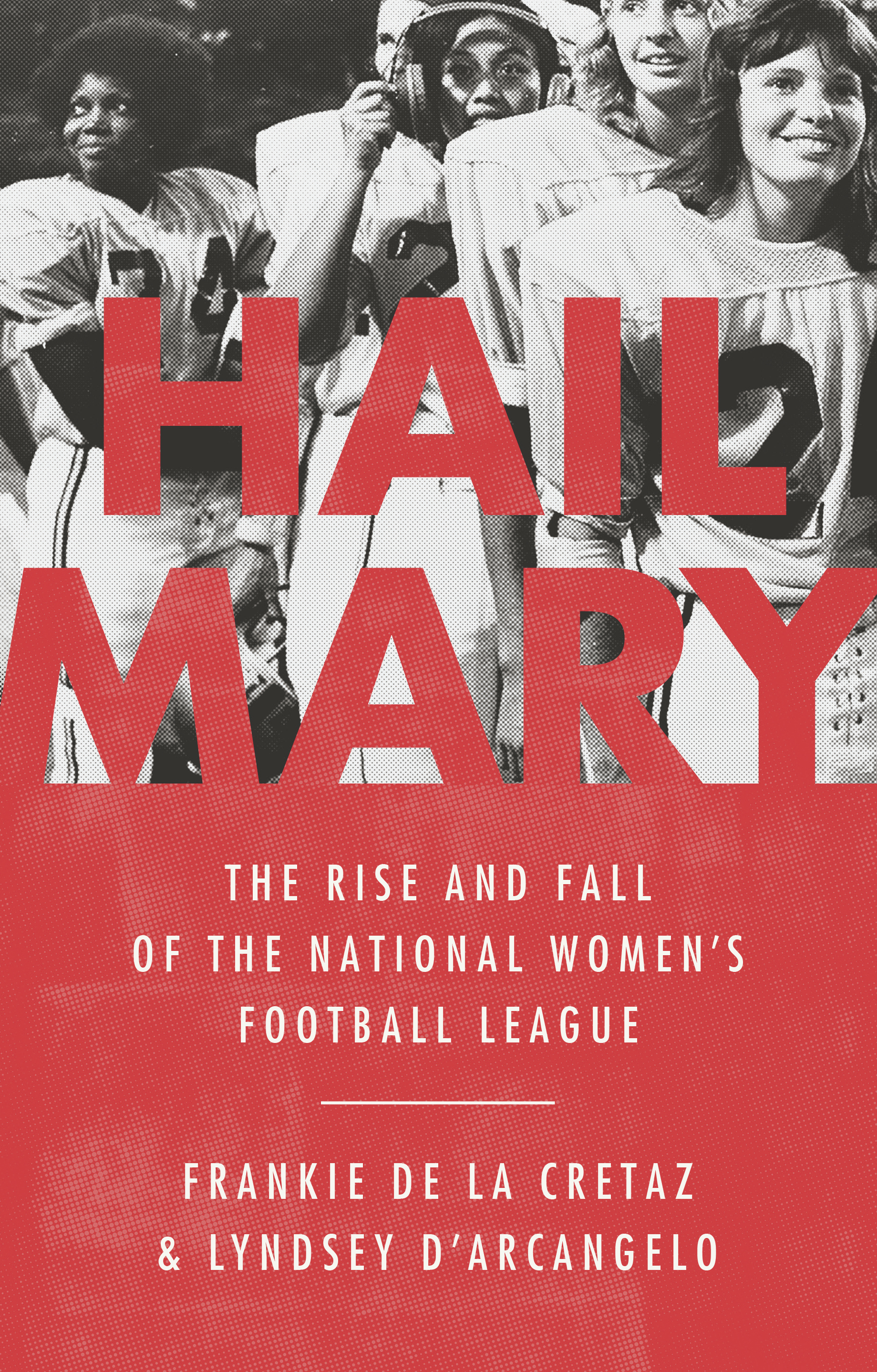

Hail Mary

The Rise and Fall of the National Women's Football League

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 2, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The groundbreaking story of the National Women’s Football League, and the players whose spirit, rivalries, and tenacity changed the legacy of women’s sports forever.

In 1967, a Cleveland promoter recruited a group of women to compete as a traveling football troupe. It was conceived as a gimmick—in the vein of the Harlem Globetrotters—but the women who signed up really wanted to play. And they were determined to win.

Hail Mary chronicles the highs and lows of the National Women’s Football League, which took root in nineteen cities across the US over the course of two decades. Drawing on new interviews with former players from the Detroit Demons, the Toledo Troopers, the LA Dandelions, and more, Hail Mary brings us into the stadiums where they broke records, the small-town lesbian bars where they were recruited, and the backrooms where the league was formed, championed, and eventually shuttered. In an era of vibrant second wave feminism and Title IX activism, the athletes of the National Women’s Football League were boisterous pioneers on and off the field: you’ll be rooting for them from start to finish.

-

“Educational, entertaining, and uplifting.”Shea Serrano, New York Times bestselling author

-

“All too often, the history of women's sports lies buried beneath the surface, never seeing the light of recognition. Britni and Lyndsey do the historic work of bringing this story to life. In this vivid account, they give us a much needed record of the women who helped pave the way so we could all exist today. I'm grateful to know these women who blazed the trail I walked upon.”Layshia Clarendon, WNBA player for the Minnesota Lynx

-

“Hail Mary tells the definitive story of the National Women’s Football League—the touchdowns, the fumbles, the passion, the power. These are stories that nearly vanished—or in some cases, were purposely erased from football’s history—but through D'Arcangelo and de la Cretaz’ deep dive, they’re brought back to life in the voices of the players. The NWFL’s imprint on the game of football is indisputable.”Tony Reali, host of ESPN’s Around the Horn

-

“De la Cretaz and D’Arcangelo graciously and painstakingly piece together the story of a rarely remembered league and the women whose love of football made the unlikely possible. The NWFL is an important part of the history of women’s sports, and in telling its story, the authors offer a throughline from the gridiron gals of yesteryear to the female footballers of today.”Sarah Spain, host of ESPN’s Spain & Company

-

“Sport demands examination of its hidden histories, especially when involving groups of marginalized people. This book will be regarded as a classic of the genre. In the hands of Britni and Lyndsey, we are introduced to a world 99% of sports fans don’t know existed, and we are richer for it.”Dave Zirin, author of A People’s History of Sports in the United States

-

“Hail Mary is a glorious and galvanizing chronicle celebrating no-longer-forgotten gridiron greats.”Oprah Daily

-

“You’ve likely heard of “A League of their Own,” a movie that captured the magic of a women’s pro baseball team that once thrived in the U.S. Britni de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo deliver equally enjoyable stories of another remarkable professional women’s league that got little attention. They showcase the scrappy women’s pro football league that operated in the United States in the 1970s.”Los Angeles Times, “10 sports books we loved in 2021”

-

“De la Cretaz and D’Arcangelo present an entertaining history of the National Women’s Football League… Without overstating the case, de la Cretaz and D’Arcangelo demonstrate how this overlooked chapter in American sports blazed a successful trail for today’s women athletes. This underdog story is a delight.”Publishers Weekly

-

“If you think male football players are tough, step aside. Because female football players have to be tougher. Look no further than Hail Mary to see why.”Yahoo Sports

-

“The authors bring these women — and their teams, and the struggles they faced, and the joys they felt — to life. The extensive research and reporting that went into the book is clear.”Alma

-

“[S]portswriters Britni de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo delve into the history of the largely forgotten women’s football league…readers come to know the players and the teams they called family. The authors strike a good balance between on-the-field and off-the-field action, making the reading as riveting as it is informative. Hail Mary is a necessary and comprehensive history of a league far ahead of its time.”Christian Science Monitor

- On Sale

- Nov 2, 2021

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645036623

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use