Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

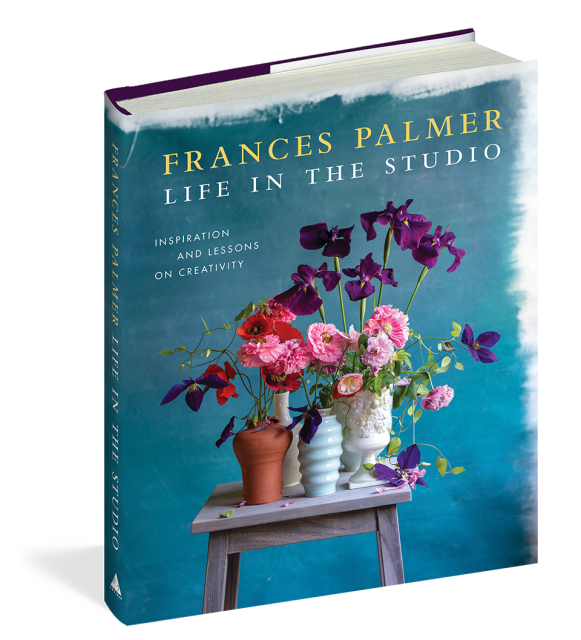

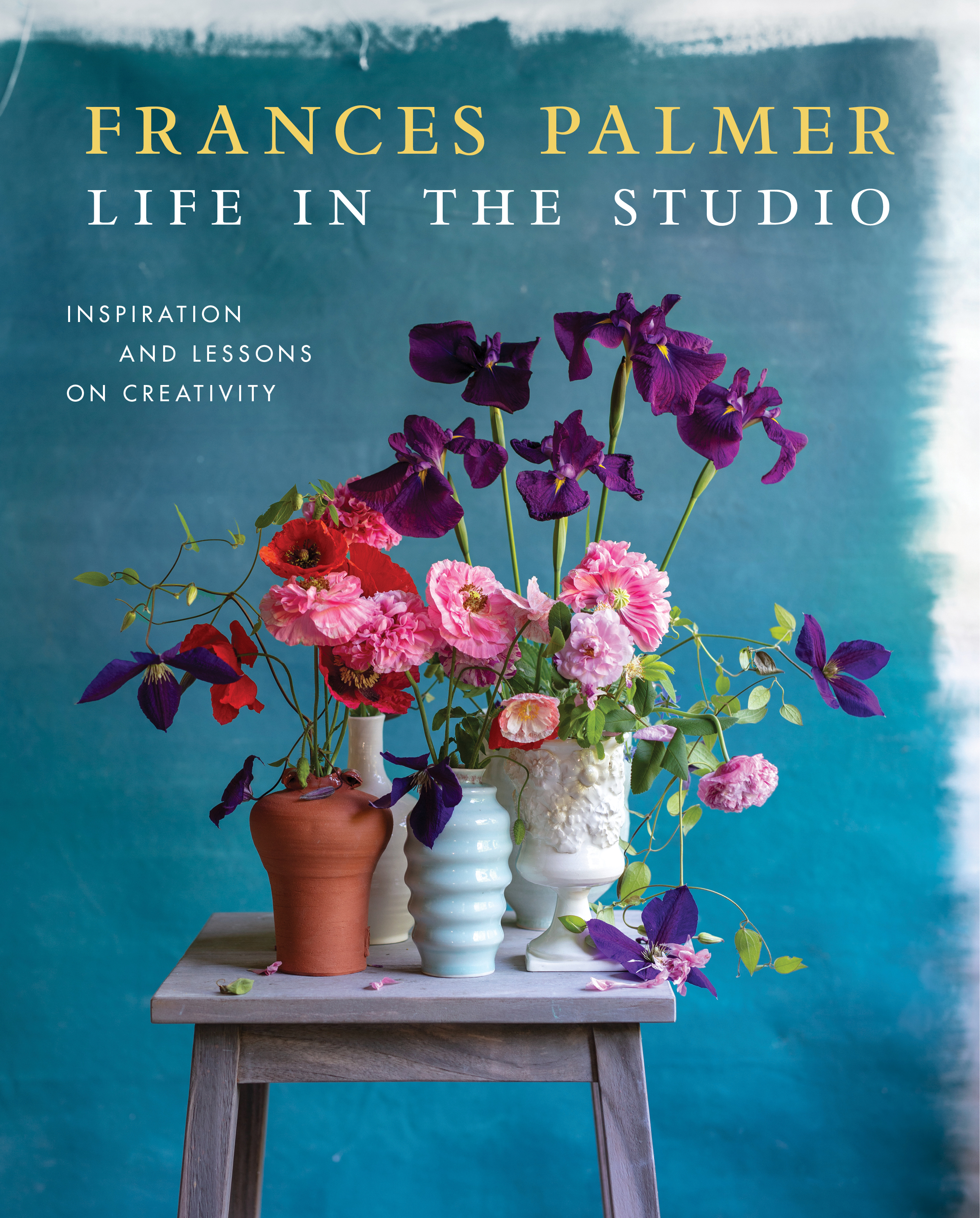

Life in the Studio

Inspiration and Lessons on Creativity

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 6, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Roll-up-your-sleeves advice on throwing pottery, growing dahlias, cooking her tried-and-true recipes, and everything in between.”

—Martha Stewart Living

“Suited to any type of creative, offering up lessons on inspiration and creativity that are sure to bring out your inner talent.”

—House Beautiful, Best New Design Books

What makes a creative life? For an artist like Frances Palmer, it’s knitting all of one’s passions—all of one’s creativity—into the whole of life. And what an inspiration it is.

A renowned potter, an entrepreneur, a gardener, a photographer, a cook, a beekeeper, Palmer has over the course of three decades caught the attention not only of the countless people who collect and use her ceramics but also of designers and design lovers, writers, and fellow artists who marvel at her example. Now, in her first book, she finally tells her story, in her own words and images, distilling from her experiences lessons that will inspire a new generation of makers and entrepreneurs.

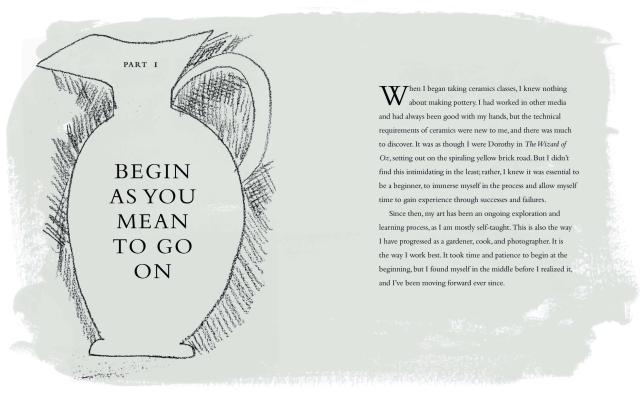

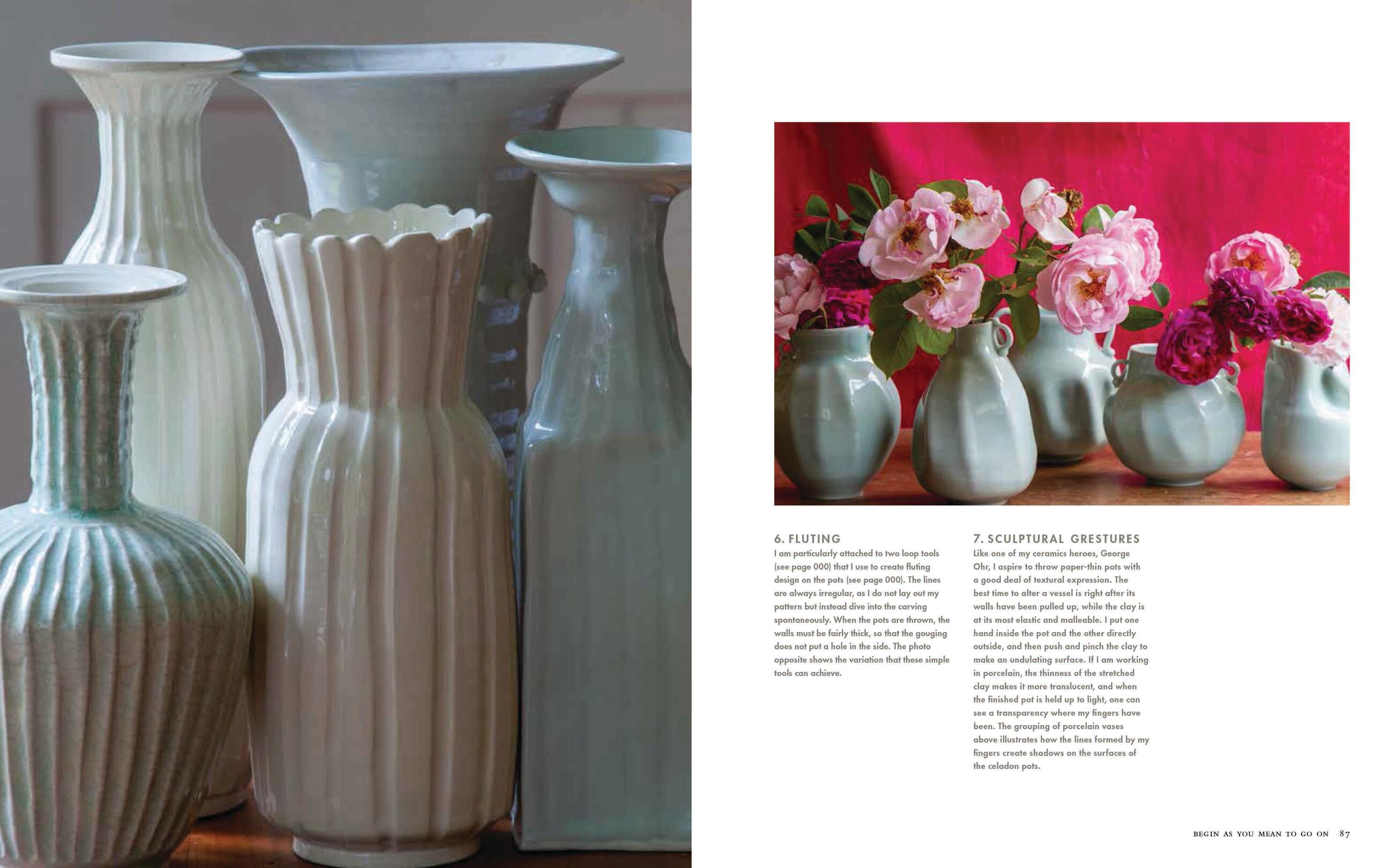

Life in the Studio is as beautiful and unexpected as Palmer’s pottery, as breathtakingly colorful as her celebrated dahlias, as intimate as the dinners she hosts in her studio for friends and family. There are insights into making pots—the importance of centering, the discovery that clay has a memory. Strategies for how to turn a passion into a business—the value to be found in collaboration, what it means to persevere, how to develop and stick to a routine that will sustain both enthusiasm and productivity. There are also step-by-step instructions (for throwing her beloved Sabine pot, growing dahlias, building an opulent flower arrangement). Even some of her most tried-and-true recipes.

The result is a portrait of a unique artist and a singularly generous manual on how to live a creative life.

-

“Roll-up-your-sleeves advice on throwing pottery, growing dahlias, cooking her tried-and-true recipes, and everything in between.”

—Martha Stewart Living

“Though Frances Palmer is best known as a ceramicist, she's a multitalented creative, whose passions include gardening, flower arranging, and entertaining. Her book is appropriately suited to any type of creative, offering up lessons on inspiration and creativity that are sure to bring out your inner talent.”

—House Beautiful, Best New Design Books

“The book is filled with Palmer’s essays detailing her inspiration, processes, and even failures, interspersed with encyclopedic passages on how to build a pot, create a floral arrangement, or cultivate bulbs (particularly her favorite, dahlias). Peppered within are homey recipes for dishes like roast chicken or almond cake, artfully photographed on some of Palmer’s handmade servingware, as well as sections on companion projects like beekeeping.”

—Galerie magazine

“Life in the Studio left us breathless with delight. It is instructional, gorgeous, and generous—Frances shares her very personal journey with us, giving a true understanding of her craft and process and happily embracing the unpredictability of her chosen pursuits. . . . A treasure.”

—Flower magazine

“This very intimate portrait of a potter, gardener, photographer, and entrepreneur is guaranteed to, as its title insists, inspire. . . . Demands to be viewed again and again and again.”

—Booklist, starred review

“This is a glorious and uplifting book. Frances has an overspilling talent for making the world a more generous place through ceramics, gardens, and food. I loved it.”

—Edmund de Waal

“I have always loved the craft of Frances Palmer. The pottery she creates is practical and useful, quirky and original, and now, in Life in the Studio, we can see the many ways her work comes full circle: The flowers she grows look amazing in her distinctive vases and pots, as does the food she makes to serve on the plates she fashions.”

—Martha Stewart

“Frances Palmer’s work represents the highest quality in American craftsmanship.”

—Aerin Lauder

“I need two copies of this beautiful book: one to sit proudly on my bookshelves, and one to follow me to my kitchen and garden, where it will soon get covered in fingerprints, dirt, and spots of water. It will be much used and loved.”

—Bunny Williams

“Frances Palmer is as generous as she is talented, an incredible role model for me and so many other creative people. I’ve been waiting for this book ever since I discovered Frances’s work, and it has exceeded all my expectations. The depth of the subject matter, the heartfelt essays, the beautiful photography, and the wisdom that Frances shares are sure to inspire and change lives.”

—Erin Benzakein, New York Times bestselling author of Floret Farm’s A Year in Flowers

- On Sale

- Oct 6, 2020

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579659059

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use