Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

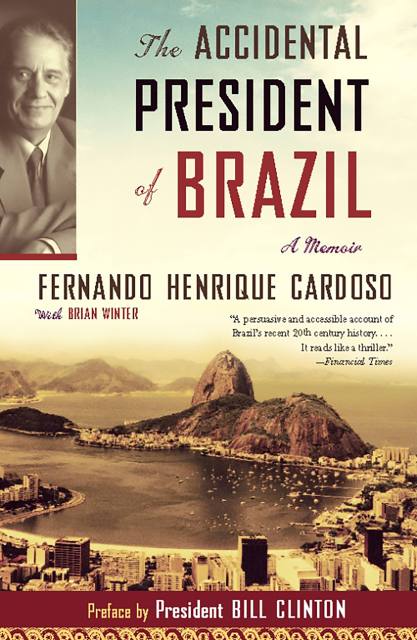

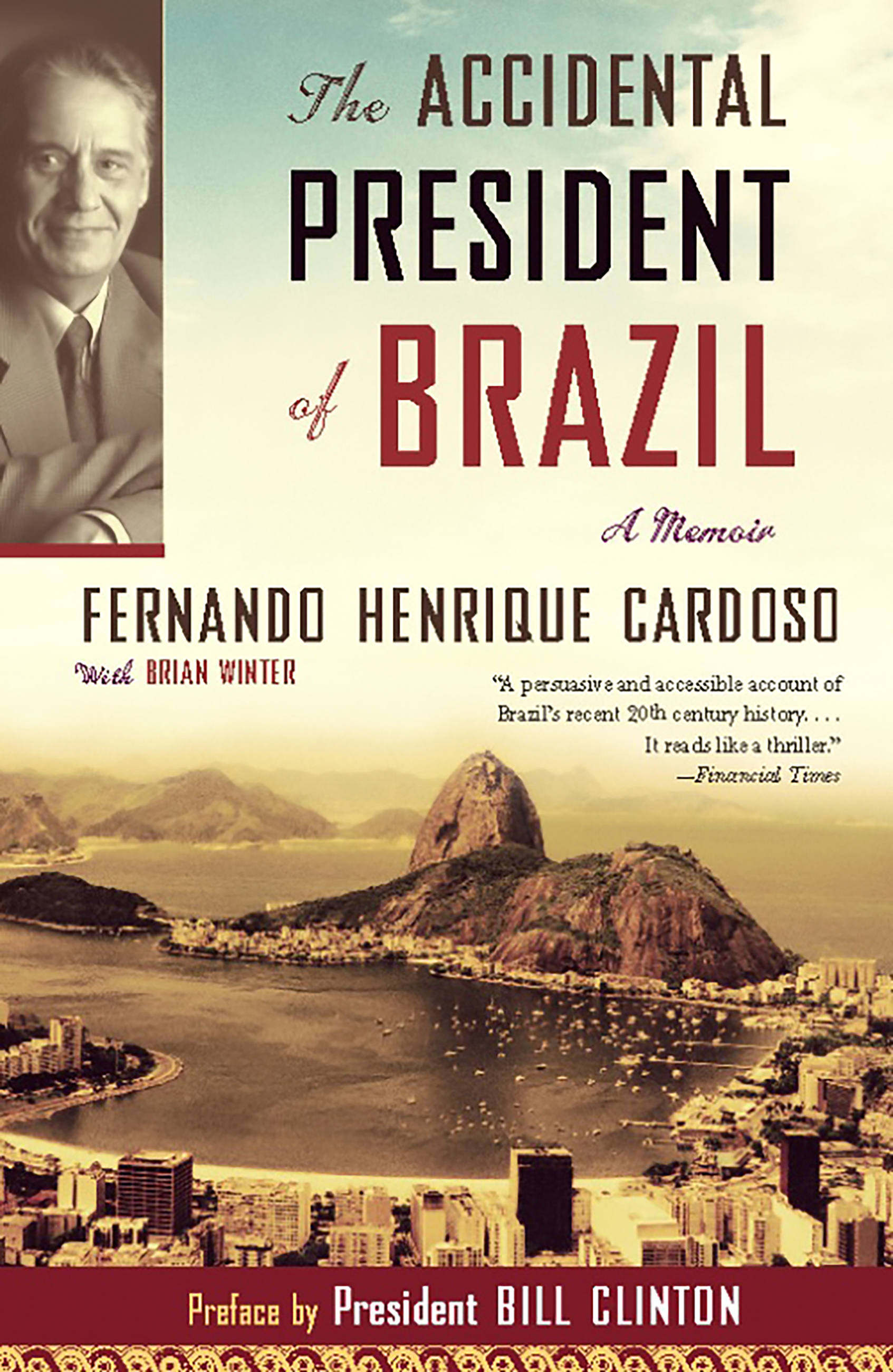

The Accidental President of Brazil

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 27, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This was just one of the turns in a largely unscripted and sometimes unwanted political career. In exile during the harshest period of the junta that ruled Brazil for twenty years, Cardoso started his political life with a tentative run for the Federal Senate in 1978. Within fifteen years, and despite himself, this former sociologist was running the country.

And what a country! Brazil, it is often said, is on the edge of modernity, striding with one foot in mid-air towards the future, the other still rooted deep in a traditional past. It is a land of sophisticated music and brutal gold-digging, of the next global superpower and the last old-time coffee plantations. It is gloriously ungovernable, irrepressibly attractive, and home to the family, friends and extraordinary life of Fernando Henrique Cardoso. This is his story and his love song to his country.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 27, 2007

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586485962

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use