Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

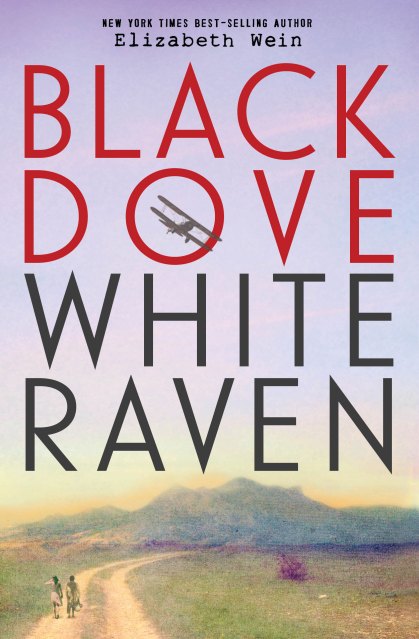

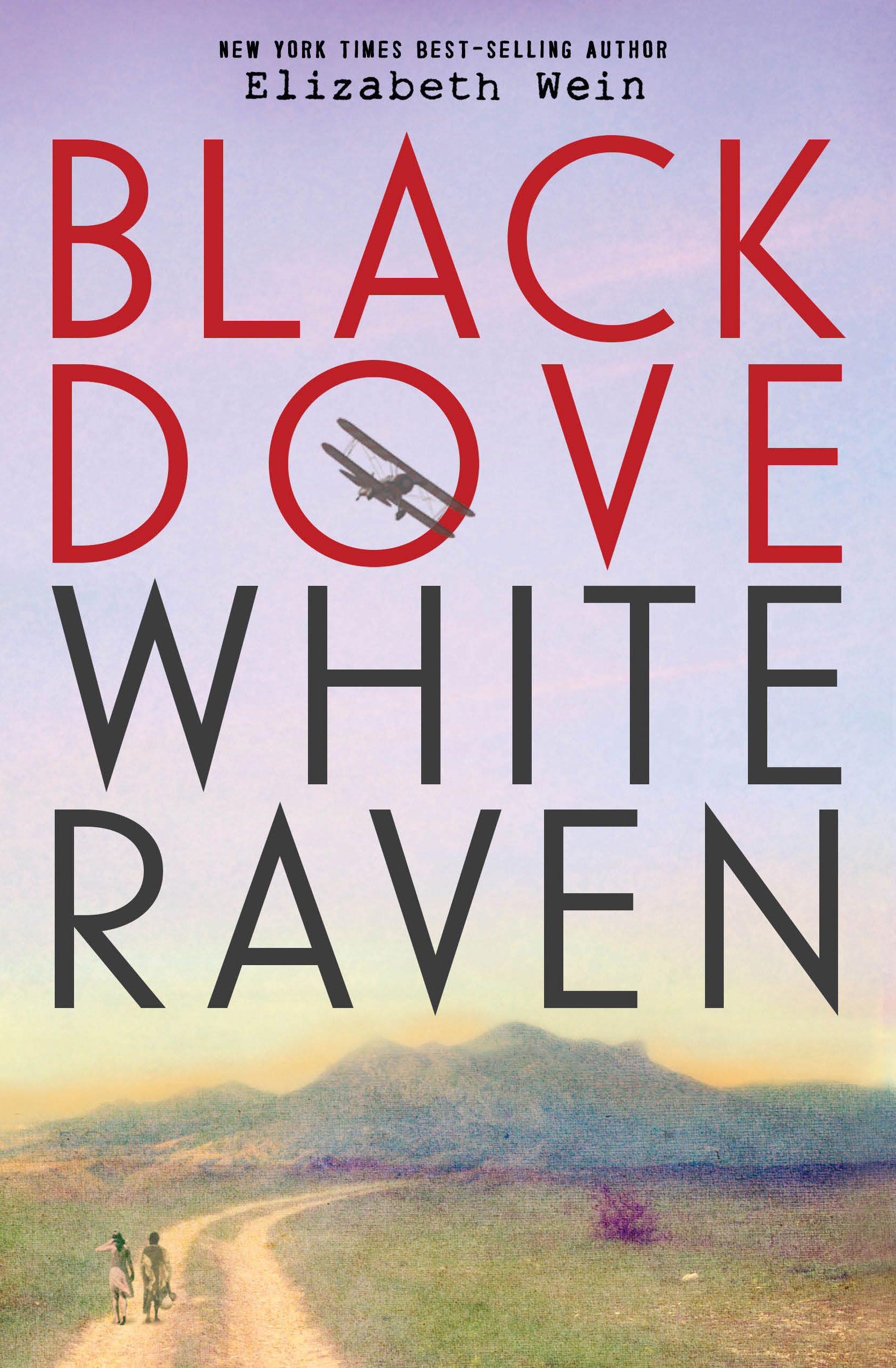

Black Dove White Raven

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Format

Format:

- ebook $7.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 31, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Emilia and Teo's lives changed in a fiery, terrifying instant when a bird strike brought down the plane their stunt pilot mothers were flying. Teo's mother died immediately, but Em's survived, determined to raise Teo according to his late mother's wishes-in a place where he won't be discriminated against because of the color of his skin. But in 1930s America, a white woman raising a black adoptive son alongside a white daughter is too often seen as a threat.

Seeking a home where her children won't be held back by ethnicity or gender, Rhoda brings Em and Teo to Ethiopia, and all three fall in love with the beautiful, peaceful country. But that peace is shattered by the threat of war with Italy, and teenage Em and Teo are drawn into the conflict. Will their devotion to their country, its culture and people, and each other be their downfall or their salvation?

In the tradition of her award-winning and bestselling Code Name Verity, Elizabeth Wein brings us another thrilling and deeply affecting novel that explores the bonds of friendship, the resilience of young pilots, and the strength of the human spirit.

Genre:

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "For me, Code Name Verity is the best of both worlds: an exciting, well-researched masterpiece of historical fiction with a contemporary sensibility....It brought me to tears to realize that I'll never be able to read it again for the first time. That is how powerful a story this is."Richie's Picks

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "It has been a while since I was so captivated by a character in YA fiction Code Name Verity is one of those rare things: an exciting-and affecting-female adventure story."The Guardian

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "Maddie and Verity's extraordinary bravery is reflected in frank narrative as they both fight against time and a horrific, powerful enemy...The themes of hope, friendship, and determination even in the most impossible situations are relevant to all readers."VOYA

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "The unforgettable Code Name Verity played with my mind, and then it ripped out my heart."Nancy Werlin, New York Times best-selling author

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "The word crossover appears many times on publisher information sheets, but this is the real deal. An incredibly assured debut novel, full of convincing detail, heart-stopping emotion and tension. I have high hopes for Code Name Verity."The Bookseller

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY * "If you pick up this book, it will be some time before you put your dog-eared, tear-stained copy back down."Booklist (starred review)

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY * "This novel positively soars."The Horn Book (starred review)

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY * "[A] taut, riveting thriller. Readers will be left gasping for the finish, desperate to know how it ends."School Library Journal (starred review)

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY * "[An] innovative spy tale built to be savored."Bulletin of the Center for Children?s Books (starred review)

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY *"A riveting and often brutal tale of WWII action and espionage with a powerful friendship at its core. [an] expertly crafted adventure."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY * "A carefully researched, precisely written tour de force; unforgettable and wrenching."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "A fiendishly plotted mind game of a novel, the kind you have to read twice."The New York Times

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "I closed this book feeling I'd met real people I'd never forget. Code Name Verity's characters don't just stick with me-they haunt me. I just can't recommend this book enough."Maggie Stiefvater, author of the New York Times best-selling Shiver trilogy, The Scorpio Races & Books of Faerie

-

PRAISE FOR CODE NAME VERITY "This astonishing tale of friendship and truth will take wing and soar into your heart."Laurie Halse Anderson, New York Times best-selling author of Speak, Fever 1793 and Wintergirls

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE " Rose Under Fire' is bound to soar into the promised land of young adult books read by actual adults-and deservedly so, because Wein's unself-consciously important story is timeless, ageless and triumphant."The Los Angeles Times

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE "Wein's second World War II adventure novel - the first, Code Name Verity,' was highly praised last year - captures poignantly the fragility of hope and the balm forgiveness offers."The New York Times

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE * "Readers will connect with Rose and be moved by her struggle to go forward, find her wings again, and fly."School Library Journal, starred review

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE * "Wein excels at weaving research seamlessly into narrative and has crafted another indelible story about friendship borne out of unimaginable adversity."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE * "[A]lthough the story's action follows [Code Name Verity]'s, it has its own, equally incandescent integrity. Rich in detail, from the small kindnesses of fellow prisoners to harrowing scenes of escape and the Nazi Doctors' Trial in Nuremburg, at the core of this novel is the resilience of human nature and the power of friendship and hope."Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE "The horror of the camp, with its medical experimentation on Polish women-called Rabbits-is ably captured. Yet, along with the misery, Wein also reveals the humanity that can surface, even in the worst of circumstances."Booklist

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE "[A]n impressive story of wartime female solidarity."The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE "[T]he author manages the neat trick of both conveying an enormous amount of historical information while also providing a nail-biting, edge-of-your-seat plot peopled with vivid, imperfect and believable characters."RT Book Reviews

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE * "At once heartbreaking and hopeful, Rose Under Fire will stay with readers long after they have finished the last page."VOYA, starred review

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE * "In plot and character this story is consistently involving, a great, page-turning read; just as impressive is how subtly Wein brings a respectful, critical intelligence to her subject."The Horn Book, starred review

-

PRAISE FOR ROSE UNDER FIRE Accolades

Schneider Family Book Award, Best Teen Book, 2014 Top Ten YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults, 2014 New York Times Notable Children's Books of 2013

KirkusReviews Best Books of 2013

School Library Journal's Best Books of 2013

Publishers Weekly Best Children's Books of 2013

The Children's Book Review Best Young Adult Novels of 2013

NPR Best Books of 2013

BookPage Best Children's Books of 2013

Goodreads Choice for Best Young Adult Book of 2013 nominee

CILIP Carnegie Medal 2014 nominee

A Junior Library Guild Selection

2014 Tayshas List Selection

[London] Times Best Books of the Year

Costa Children's Book Award finalist

- On Sale

- Mar 31, 2015

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781484707807

Educator Guide

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use