Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

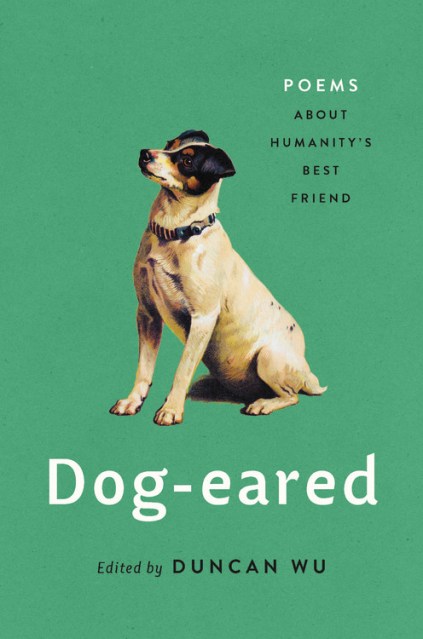

Dog-eared

Poems About Humanity's Best Friend

Contributors

Edited by Duncan Wu

Formats and Prices

Price

$25.00Price

$31.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $25.00 $31.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From Homer to Wordsworth to Gwendolyn Brooks, learn about history’s greatest writers and the furry best friends that inspired them.

Dogs are at once among the most ordinary of animals and the most beloved by mankind. But what we may not realize is that for as long as we have loved dogs, our poets have been seriously engaged with them as well.

In this collection, English professor Duncan Wu digs into the wealth of poetry about our furry friends to show how varied and intimate our relationships with them have been over the centuries. Homer recounts how Odysseus’s loyal dog recognizes his master even after his long absence. Thomas Hardy wrote poems from a pooch’s perspective, conveying a powerful sense of dogs’ innocent and trusting nature. And a multitude of writers, from Lord Byron to Emily Dickinson, have turned to poetry to mourn the loss of beloved dogs. Rich and inviting, Dog-eared is a spellbinding collection of poetic musings about humans and dogs and what they mean to each other.

Genre:

-

"Cats get all the credit for being mysterious, but dogs are deep. Duncan Wu, a fierce dog-lover himself, knows this truth. The dog poems he's assembled here -- so many of them little-known, so many of them revelations-testify to the fact that humans, from Homer to Dorothy Parker to Michael Ondaatje, have been trying to capture the essential nature of their canine companions for centuries, while dogs had us humans figured out long ago."Maureen Corrigan, book critic, NPR's Fresh Air

-

"Duncan Wu has curated a collection of poems that conjure both the pleasures of great poetry and the delights that dogs bring -- or sometimes don't! This is the least sentimental of books, as Wu -- whose thoughtful stewardship guides us into many of the poems -- indicates in his introduction. Each poem invites us to consider the relationship between humans and animals and what it tells us about ourselves."Aminatta Forna, author of Happiness

-

"Dogs have held a special place in the hearts of men and women for as long humans have been humans. Duncan Wu has collected the best of these sentiments across history into a remarkable collection, proving that dogs are, and always have been, our best friends."Gregory Berns, author of What It's Like to Be a Dog

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541672932

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use