Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

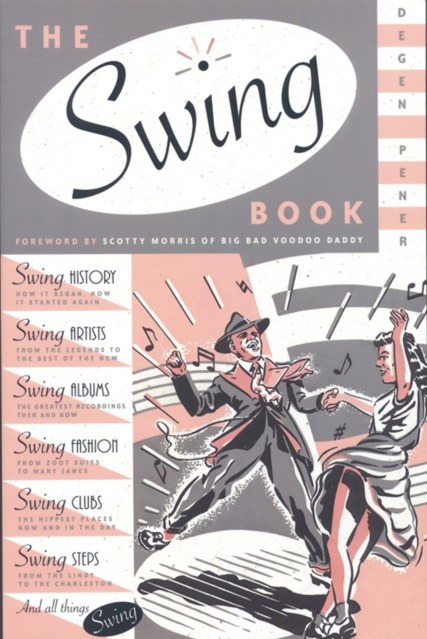

The Swing Book

Contributors

By Degen Pener

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $7.99 $9.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 27, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Ten years ago a revival of swing took place, originating in San Francisco, snowballing into today’s international resurgence. This book presents the complete history of swing music and dancing, then and now.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 27, 2009

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316076678

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use