Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

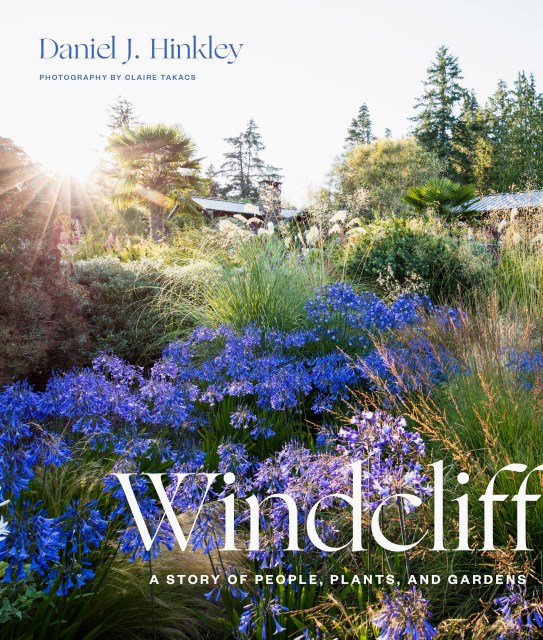

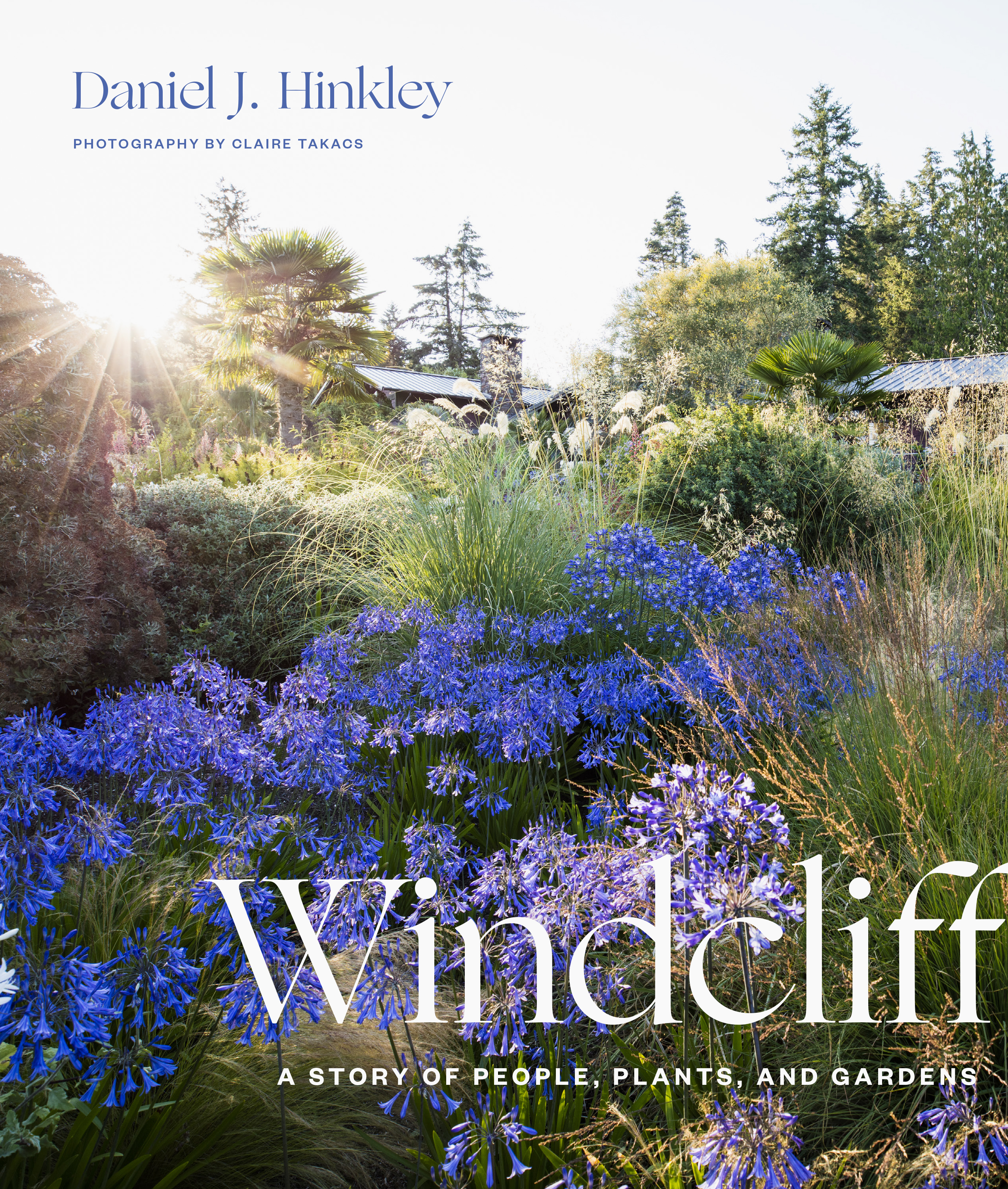

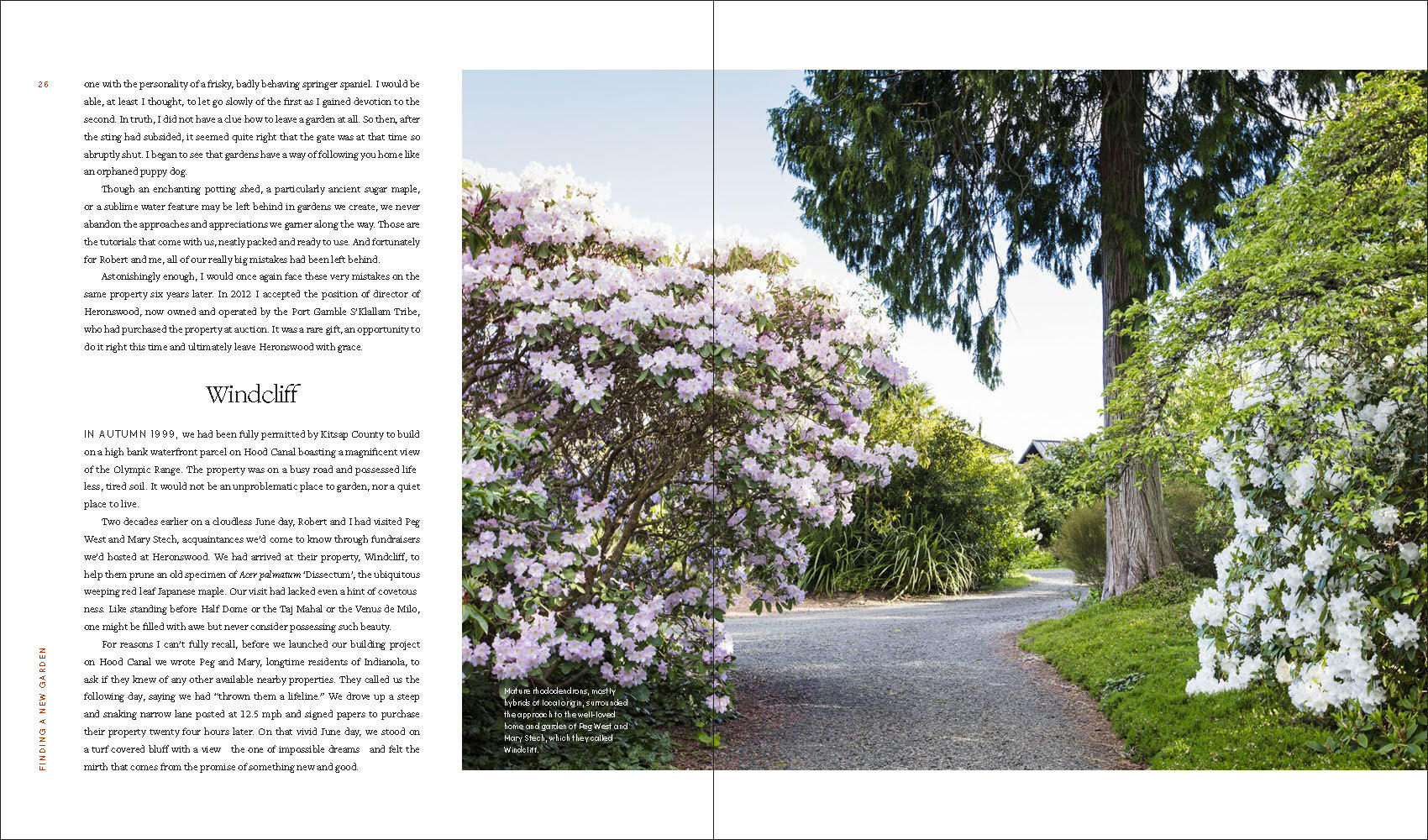

Windcliff

A Story of People, Plants, and Gardens

Contributors

Photographs by Claire Takacs

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.00Price

$45.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 22, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Dan Hinkley is a rare man, generous, inspired, and gifted with an eye for beauty that is given to few people. How I long to wander again in the galloping beauty of his garden at Windcliff. Here it is, in all its inspiring wonder.” —Anna Pavord, author of Landskipping and The Curious Gardener

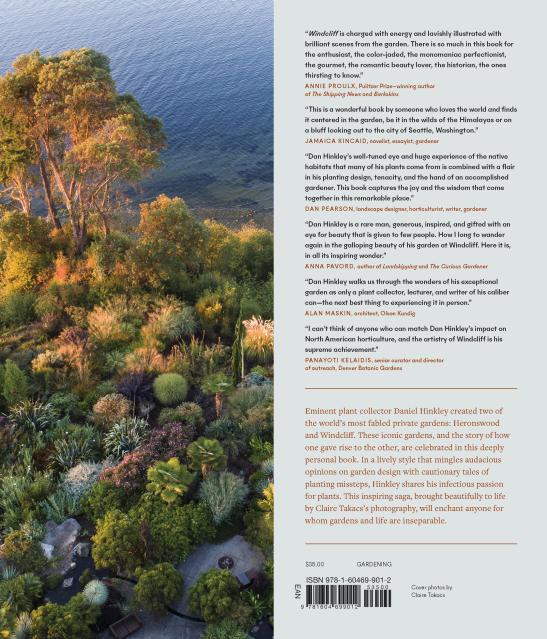

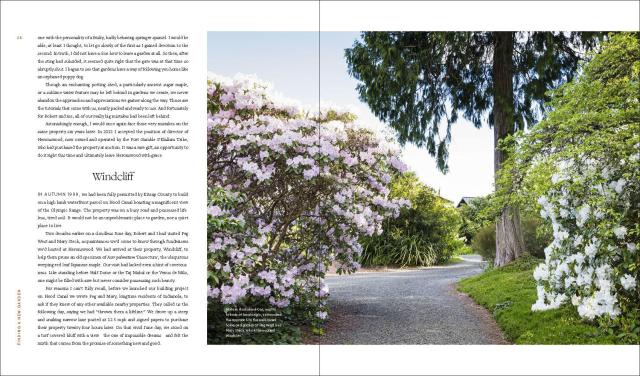

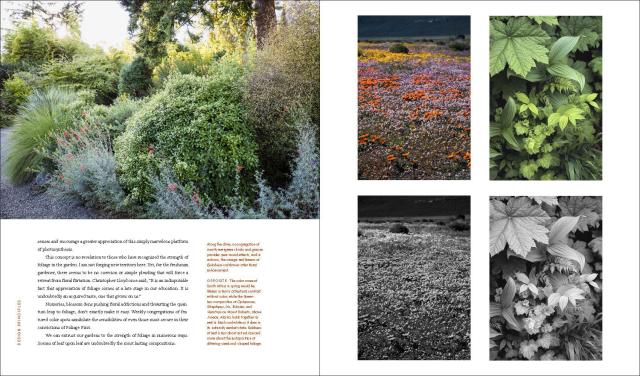

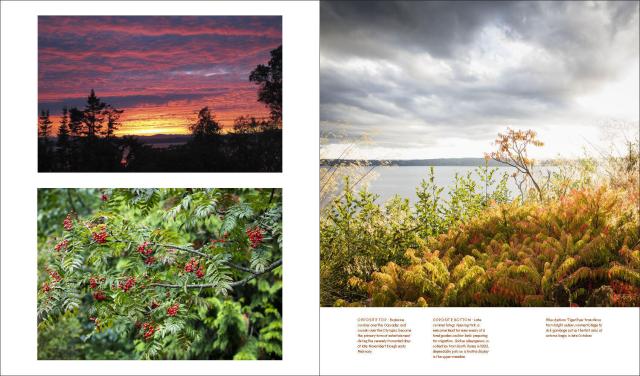

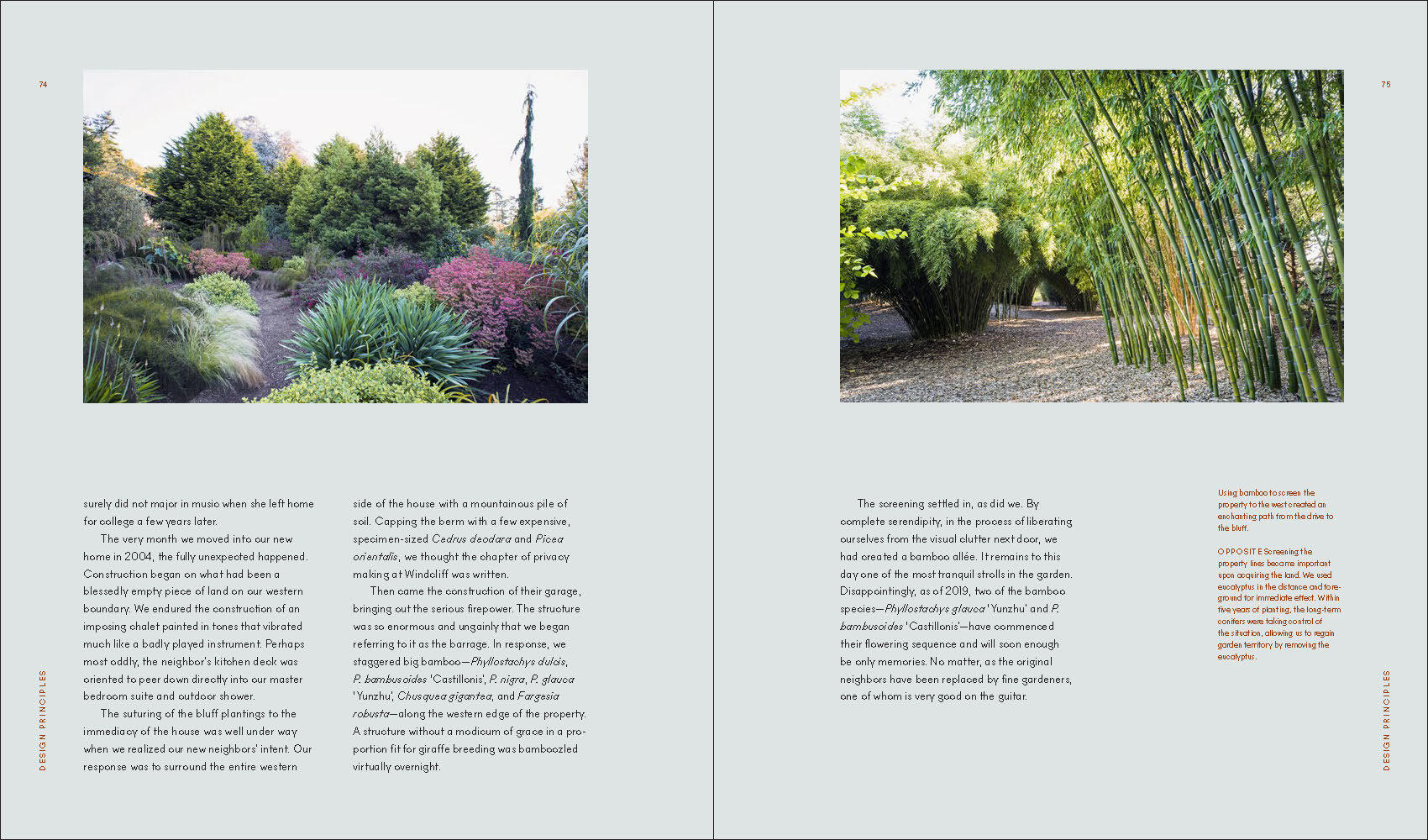

Daniel Hinkley is widely recognized as one of the foremost modern plant explorers and one of the world’s leading plant collectors. He has created two outstanding private gardens—Heronswood and Windcliff. Both gardens, and the story of how one begat the other, are beautifully celebrated in Hinkley’s new book, Windcliff.

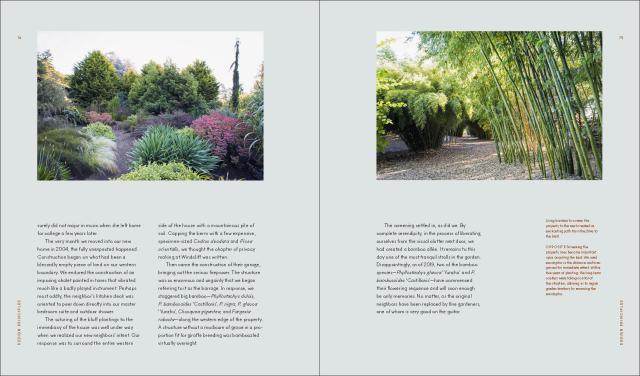

In these pages you will delight in Hinkley’s recounting of the creation of his garden, the stories of the plants that fill its space, and in his sage gardening advice. Hinkley’s spirited ruminations on the audacity and importance of garden-making—contemplations on the beauty of a sunflower turning its neck from dawn to dusk, the way a plant’s scent can spur a memory, and much more—will appeal to the hearts of every gardener.

Filled with Claire Takacs’s otherworldly photography, Windcliff is spectacular for both its physical beauty and the quality of information it contains.

Genre:

-

“This is a wonderful book by someone who loves the world and finds it centered in the garden, be it in the wilds of the Himalayas or on a bluff looking out to the city of Seattle, Washington." —Jamaica Kincaid, novelist, essayist, gardener“Dan Hinkley is a rare man, generous, inspired, and gifted with an eye for beauty that is given to few people. How I long to wander again in the galloping beauty of his garden at Windcliff. Here it is, in all its inspiring wonder.” —Anna Pavord, author of Landskipping and The Curious Gardener“Dan Hinkley walks us through the wonders of his exceptional garden as only a plant collector, lecturer, and writer of his caliber can—the next best thing to experiencing it in person.” —Alan Maskin, architect, Olson Kundig“I can’t think of anyone who can match Dan Hinkley’s impact on North American horticulture, and the artistry of Windcliff is his supreme achievement.” —Panayoti Kelaidis, senior curator and director of outreach, Denver Botanic Gardens

“Lays out the wonder of a life spent discovering, testing, and growing. My hope for this book is that it will enable a wider audience to see plants as clearly and carefully as Dan Hinkley. In doing so, may be we’ll see the world more clearly ourselves.” —The American Gardener

“A book magnificently enriched with photographs by the author and Claire Takacs.” —The Wall Street Journal

“Magical images and revelatory anecdotes and humor abound in Hinkley’s garden autobiography. Windcliff is worth reading for glimpses of the rarefied world of international plant exploration and stories about the making of an extraordinary garden.” —Digging

“This is a wonderful book for any plant person. It’s beautifully illustrated by Australian photographer Claire Takacs… It’s one of those books that is readable, and yes, it’s visually inspiring.” —Growing with Plants

“A perfect book for all those who appreciate gardening.” —Garden Design Magazine

“A beautiful hardcover…and a dirt-cheap way to travel the world as an armchair explorer and designer and is a book that will inspire experimentation and new planting ideas.” —The News Tribune

“Equal parts memoir, meditation, and blueprint for creating your own slice of heaven. An inspiration to all gardeners, no matter where they live in the West.” —Sunset

“A gem… Remarkable photographs by Claire Takacs brilliantly capture the light and movement of this kinetic and lively landscape.” —The Seattle Times

“Windcliff will inspire you, and the photography will get you through the bleak, snowy winter.” —The Spokesman Review

“The photographs are breathtaking, and the text is a masterclass in adventurous planting design as one would expect from this celebrated plantsman, nursery man and plant hunter.” —The Sunday Telegraph

“Home gardeners will be inspired by this book, especially Hinkley’s humbling but encouraging words.” —The Oregonian

“Hinkley’s writing is very visual…the garden is further brought to life with exquisite photography by Claire Takacs.” —The Orange County Register

“An inspiring read about the creation of a unique garden, and also a casual stroll through both familiar and uncommon members of the plant kingdom… Windcliff ranks very high among the best garden books of 2020.” —The Santa Cruz Sentinel

“Some very practical advice for home gardeners… Hinkley’s writing is very visual, but the garden is further brought to life with exquisite photography from Claire Takacs.” —Mercury News

“Windcliff is amusing, educational, inspirational, and refreshingly filled with moments of vulnerability and humility.” —Garden Rant

“Hinkley’s insights into the challenges of making a great garden, and his generosity in sharing what he has learned about plants and gardens over half a century of passionate involvement in growing things, makes for a very satisfying read.” —The Sydney Morning Herald

“Part inspiration, part botanical reference, Windcliff is a beautiful, literary take on gardening and all that it means.” —Chantecaill

- On Sale

- Sep 22, 2020

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604699012

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use