By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

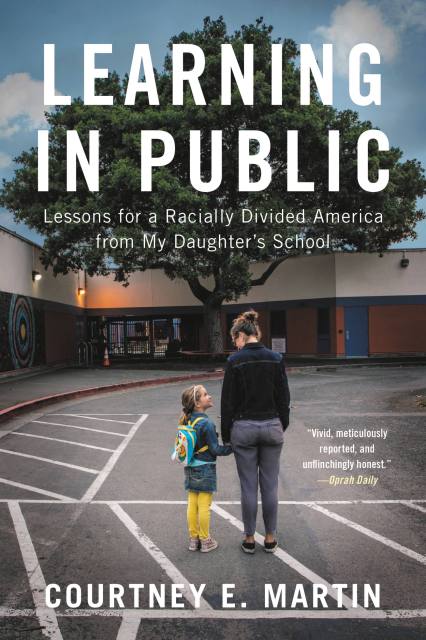

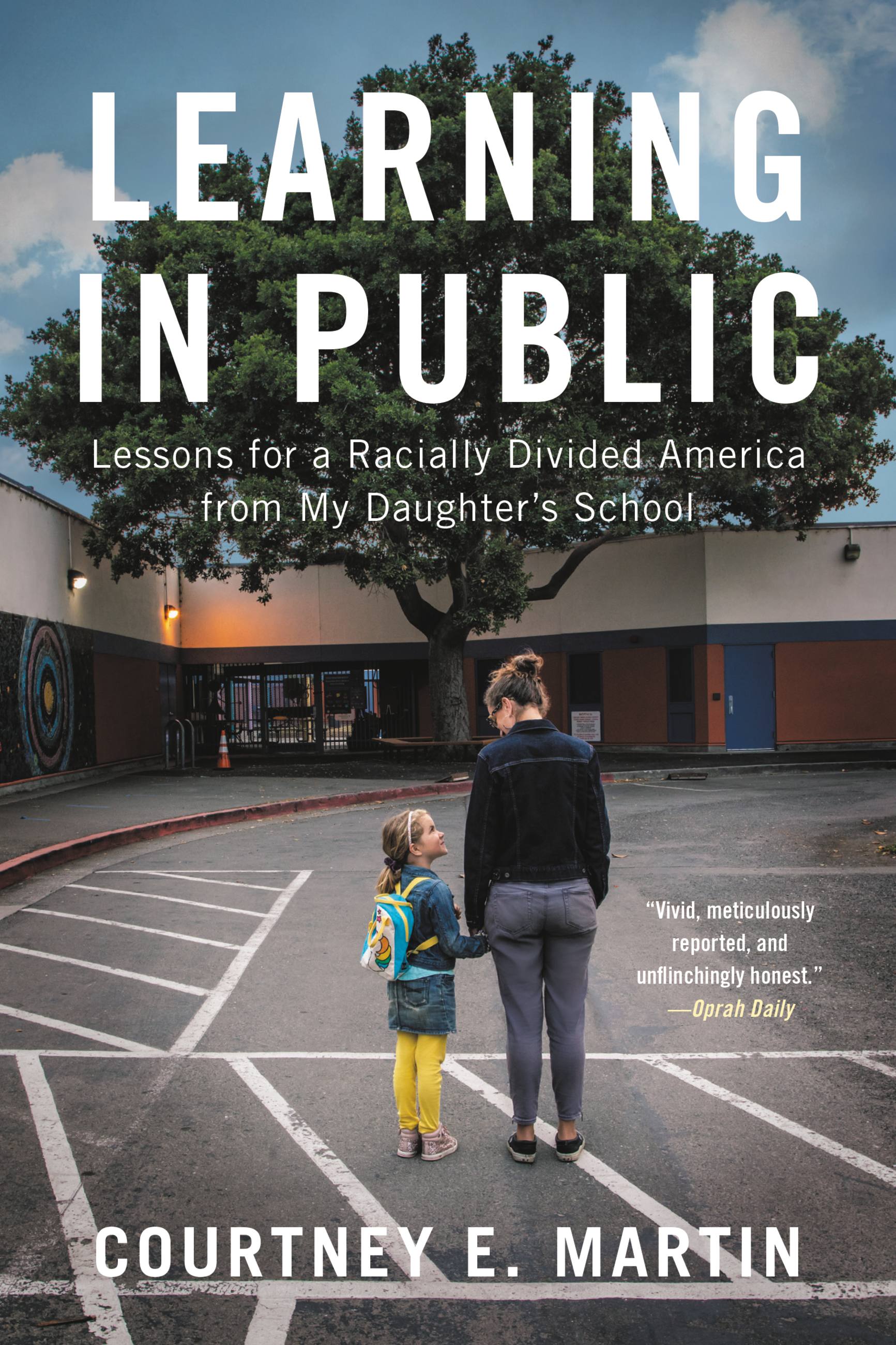

Learning in Public

Lessons for a Racially Divided America from My Daughter's School

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 3, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This "provocative and personally searching"memoir follows one mother's story of enrolling her daughter in a local public school (San Francisco Chronicle), and the surprising, necessary lessons she learned with her neighbors.

From the time Courtney E. Martin strapped her daughter, Maya, to her chest for long walks, she was curious about Emerson Elementary, a public school down the street from her Oakland home. She learned that White families in their gentrifying neighborhood largely avoided the majority-Black, poorly-rated school. As she began asking why, a journey of a thousand moral miles began.Learning in Public is the story, not just Courtney’s journey, but a whole country’s. Many of us are newly awakened to the continuing racial injustice all around us, but unsure of how to go beyond hashtags and yard signs to be a part of transforming the country. Courtney discovers that her public school, the foundation of our fragile democracy, is a powerful place to dig deeper.

Courtney E. Martin examines her own fears, assumptions, and conversations with other moms and dads as they navigate school choice. A vivid portrait of integration’s virtues and complexities, and yes, the palpable joy of trying to live differently in a country re-making itself. Learning in Public might also set your family’s life on a different course forever.

-

A Lit Hub Nonfiction Books You Should Read this Summer

-

One of the Top Five Books I Want to Read This Year for CEO of TEDWomen Pat Mitchell

-

"An honest, searching, and progressive book that will spark debate."Kirkus

-

“Martin chronicles her efforts to narrow the space between her progressive principles and her behavior…a compelling account of the benefits of diverse, integrated schools.”Conor P. Williams, Washington Post

-

"In a vivid, meticulously-reported and unflinchingly honest way, Martin describes choosing a school for her eldest daughter in progressive Oakland and navigating both unconscious and explicit biases that force her to confront her privileges and fight against them. In the end, she concludes that the main barriers to true integration in public schools are well-meaning white mothers—without finger-pointing or absolving herself as a white savior."Oprah Daily

-

“Martin brings to her perspective on her daughter's education a self-reflection that goes well beyond her one daughter and their one family, or even their one school, placing instead the story of her white family in the racial history of the U.S. and the gross disparities seen in the American public education system. This reflection...is what allows Learning in Public to live up to its title."Shelf Awareness

-

“This is the story of what school segregation, a nationally important issue, looks like through the lens of one family’s experience.”Lit Hub

-

“Correcting the harmful legacies of racism in America is generational work. Learning in Public invites us to walk the long road of this process in beloved community. Courtney refuses to settle for the comfort and false certainty of simple answers and static moralizing. Instead, she insists on the painful discomfort and joyful awakening of transformation that’s possible when we live into the biggest questions we have through the most personal choices we make.”Mia Birdsong, author of How We Show Up

-

“Writing with equal passion as a journalist and a mother, Courtney Martin interrogates the history and the moral contradictions of “elite parenting,” gentrification, and school choice. She lives the question of how to chart a new way forward with her daughter in their neighborhood. This is a kind of modeling our society needs – as openly messy as the work of remaking our world.”Krista Tippett, host of On Being and author of Becoming Wise

-

"Learning In Public by Courtney Martin rules and I hope you read it."Garrett Bucks, The White Pages

-

“Courtney Martin reveals the tensions that progressive parents grapple with when choosing schools for their children in a limited market for “good” schools. She inspires us to ask necessary questions about race, class, and education in a country that has not yet achieved justice for all.”Dr. Dena Simmons, Founder of LiberatED and author White Rules for Black People

-

“White parents want to be instruments of change, yet don’t want our own children to 'suffer.' We want to raise anti-racists, yet segregate our kids in 'good' schools dominated by families that look like us. Courtney Martin wrestles with all of these hopes and conundrums in ways that are personal, heartfelt and, especially now, profoundly necessary.”Peggy Orenstein, author of Girls & Sex and Boys & Sex

-

“If you have ever wondered what school choice means for white families who profess racial justice and understand that, in the United States, with whom we learn is as important as what we learn, then this is a book for you. Courtney Martin understands that the choices white families make about how and with whom their children live and learn is a way to share in the doing of justice across racial divides. Honest, human, real and necessary, Learning in Public is a triumph.”Noliwe Rooks, author of Cutting School: The Segrenomics of American Education

-

“There is so much love in these pages. Courtney’s capacity to empathize with and challenge White parents’ notions of what is best for our children and our communities is what makes this book so compelling and necessary right now. She’s a master at calling out our bullshit while still calling us together.”Whitney Kimball Coe, Vice President at Center for Rural Strategies

-

“Is it possible to integrate with integrity? To advance justice one school choice at a time? Courtney Martin the writer asks such questions. Courtney Martin the mother, neighbor, and citizen lives them. Learning in Public is a powerful, unflinching chronicle of responsibility-taking: what it feels like, what it costs, what it makes possible.”Eric Liu, CEO of Citizen University and author, Become America

-

“I'm so grateful to Courtney Martin for writing Learning In Public, for so many reasons. For one, I now have the book to hand to my White parent friends when they start talking about what school they're going to choose for their kids. Two, Courtney shows White people in particular how to walk the walk and talk the talk—and how neither process is easy, orderly, or what we expect—and hope—it will be. Three, she reminds us that being a "good parent" and a "good citizen" isn't about knowing all the answers, or being the smartest one in the room. It's about being willing to not know. To be curious, to listen, to try, to fail, and to accept that morality is messy. With Learning in Public, Courtney offers the kind of radically vulnerable intelligence that we can all use much more of.”Kate Schatz, New York Times bestselling author of Rad American Women A-Z and Rad Women Worldwide

- On Sale

- Aug 3, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316428255

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use