By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

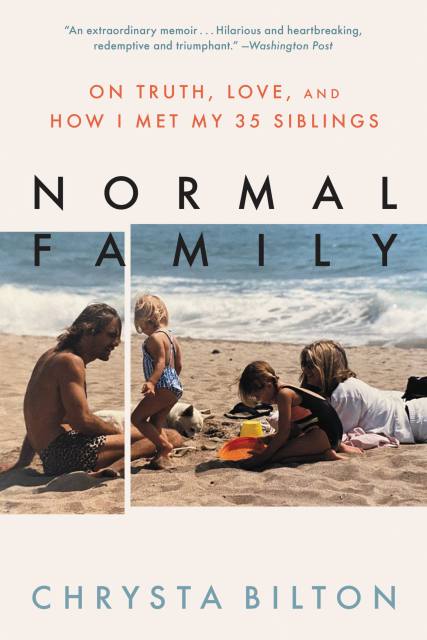

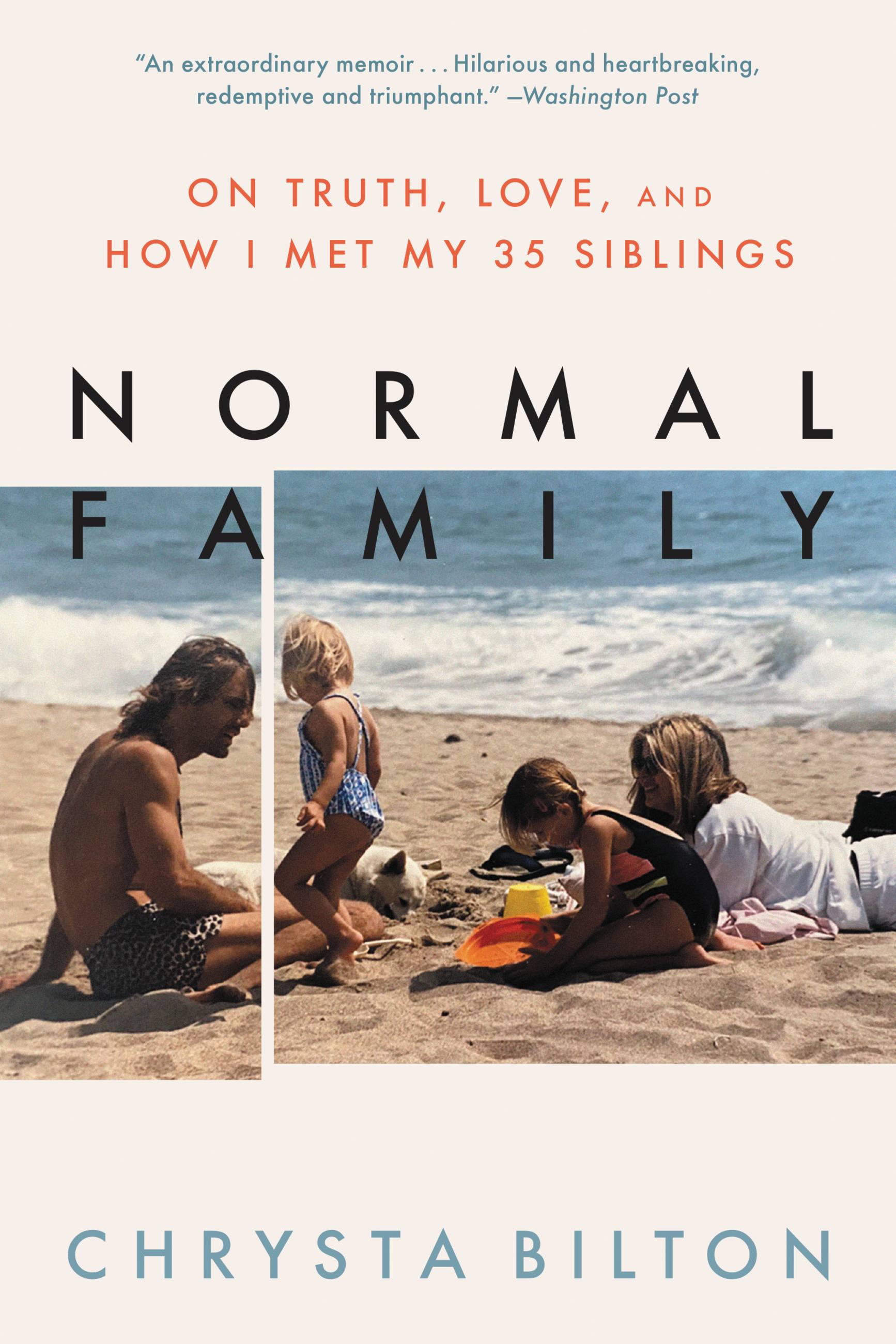

Normal Family

On Truth, Love, and How I Met My 35 Siblings

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 12, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316536523

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 12, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This riveting, nuanced memoir about unforgettable individuals thrown together by chance and DNA tells a story of nature, nurture, and coming to terms with one's true inheritance.

What is a “normal family,” and how do you go about making one? Chrysta Bilton’s magnetic, larger-than-life mother, Debra, yearned to have a child, but as a single gay woman in 1980s California, she had few options. Until one day, while getting her hair done in a Beverly Hills salon, she met a man and instantly knew he was the one she’d been looking for. Beautiful, athletic, artistic, and from a well-to-do family, Jeffrey Harrison appeared to be Debra’s ideal sperm donor.

A verbal agreement, a couple of thousand in cash, and a few squirts of a turkey baster later, and Chrysta was conceived. Over the years, Jeffrey would make regular appearances at the family home, which grew to include Chrysta’s baby sister. But how much did Debra really know about the man she’d chosen to father her daughters? And as a single mother torn between ferocious independence and abject dependence—on other women, alcohol, drugs, and the adrenaline of get-rich-quick schemes—what secrets of her own was she keeping?

It wasn’t until Chrysta was a young adult that she discovered just how much her parents had hidden from their daughters—and each other—including a shocking revelation with far-reaching consequences not only for Debra, Chrysta, and her sister, but for dozens and possibly hundreds of unsuspecting families across the country. After a lifetime of longing for a “normal family,” can Chrysta face the reality of her own, in all its complexity? Bringing us into the fold of a deeply dysfunctional yet fiercely loving clan that is anything but “normal,” this emotional roller coaster of a memoir will make you cry, laugh, and rethink the meaning of family.

Named a 'Best Book of the Summer' by LA Times, People, USA Today, Vanity Fair, The Hollywood Reporter, Amazon, Apple, Cup of Jo, Kirkus, Parade, & Today

-

“Normal Family had me absolutely riveted from beginning to end. Chrysta Bilton has woven an impeccable narrative about the explosion of love, betrayal, and addiction—not to mention the menagerie of animals—that made up her madcap and calamitous childhood. The story is dominated by Bilton’s hedonistic, cult-inclined, womanizing, unstable and uncanny lesbian single mother, who had to make it up as she went along, and is surely one of the most mesmerizing ‘characters’ in recent memoir. Normal Family narrowly escapes being a tragedy, redeemed by Bilton’s compassionate storytelling and unwavering love for her untraditional family.”Stephanie Danler, bestselling author of Stray and Sweetbitter

-

“I thought my family was complicated until I read Chrysta Bilton’s wonderful memoir about the unique—eccentric, wild, expansive—collection of irresistible characters in her life. Bilton has a big heart, gentle wisdom, keen eye and lovely wit. She’s a gifted writer with an astonishing story to tell.”David Sheff, NYT bestselling author of Beautiful Boy

-

"Bilton's warts-and-all depiction is sometimes hilarious, sometimes horrifying, always grounded in extraordinary forgiveness and resilience...A wholly absorbing page-turner that everyone will want to read. You should probably buy two."Kirkus Reviews, STARRED REVIEW

-

“Chrysta Bilton's astonishing, wildly unpredictable memoir NORMAL FAMILY starts out as rollicking and suspenseful and only ramps up from there, becoming by turns frightening, riotously funny, and finally quite moving.”Robert Kolker, New York Times bestselling author of Hidden Valley Road

-

“It’s hard to put into words the many ways this book spoke to me. Normal Family reads like a thriller with its core mystery being the very meaning of life itself: vividly specific but also universal, with family as protagonist and antagonist, but always the hero.”Ry Russo-Young, filmmaker (Nuclear Family)

-

"Eloquently written and compulsively readable, Bilton’s jaw-dropping coming-of-age memoir--and the love and survival found within its pages--is one readers won’t soon forget."Library Journal, STARRED REVIEW

-

"Every family is uniquely dysfunctional in its own way, but Bilton’s might take the cake. In her fascinating memoir, the author writes of her unconventional upbringing and discovering her father had sired dozens of children.”USA TODAY, Best Books of Summer

-

“Bilton’s twisty life story is fascinating, and her eye for detail and ability to plumb her painful past for meaning make this a riveting debut.”People Magazine

-

“shines a much-needed light on the impact of the secretive, unregulated world of sperm donations…Bilton’s deeply human narratives so aptly convey[s]…no one should ever be in the dark about his or her own origins.”Gabrielle Glaser, New York Times Book Review

-

“This remarkable and wise book is actually two memoirs, braided together with such tendresse that readers will come to believe the ironic title in earnest. Born via turkey baster to a lesbian mother with countless connections and even more schemes, Chrysta and her younger sister didn’t learn until decades later that their family secrets included one that would change everything, including their definition of ‘family.’”Bethanne Patrick, Los Angeles Times

-

“It’s an extraordinary memoir about identity, family secrets, the nature of love and forgiveness, and resilience that’s alternatively hilarious and heartbreaking, redemptive and triumphant. I couldn’t stop turning the pages, and never stopped thinking about this story long after I finished.”Aviva Loeb, Washington Post

-

“At age 23, the author learned that, owing to her estranged father’s prolific (and unregulated) sperm donations, she has at least 150 half-siblings — and that’s not even the most fascinating element of this memoir, which chronicles her bohemian upbringing in Los Angeles, floating between a hippie counterculture, rich private school kids, and even the occasional celebrity crew.”Seija Rankin, Hollywood Reporter

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use