Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

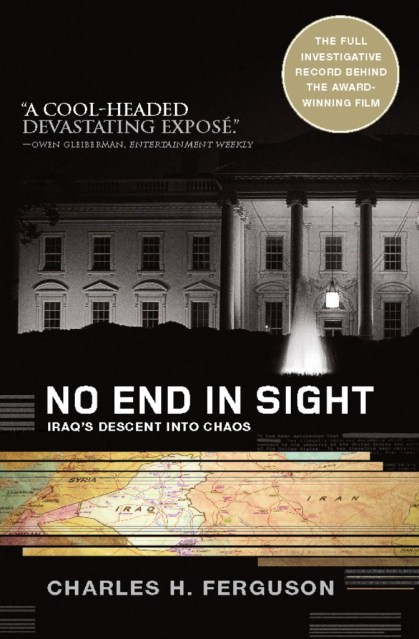

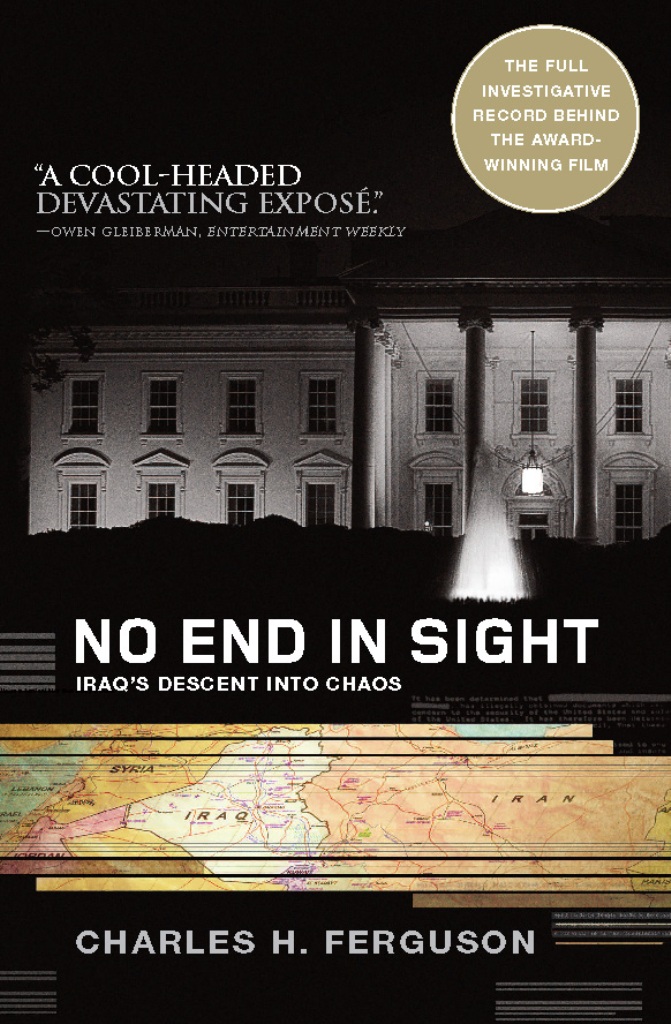

No End in Sight

Iraq's Descent into Chaos

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 23, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Culled from over 200 hours of footage collected for the film, the book provides a candid and alarming retelling of the events following the fall of Baghdad in 2003 by high ranking officials, Iraqi civilians, American soldiers, and prominent analysts. Together, these voices reveal the principal errors of U.S. policy that largely created the insurgency and chaos that engulf Iraq today — and what we could and should do about them now.

No End In Sight marks the first time Americans will be allowed inside the White House, Pentagon, and Baghdad’s Green Zone to understand for themselves the disintegration of Iraq — and how arrogance and ignorance turned a military victory into a seemingly endless and deepening nightmare of a war.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 23, 2009

- Page Count

- 672 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786732340

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use