Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

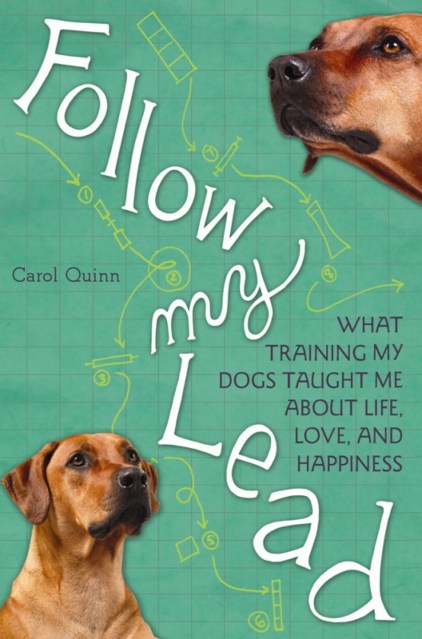

Follow My Lead

What Training My Dogs Taught Me about Life, Love, and Happiness

Contributors

By Carol Quinn

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 26, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Follow My Lead is the story of how two rambunctious dogs and a tough Eastern European dog trainer named Irina taught Carol Quinn everything she needed to know about life, love, and happiness.

It all begins when the author—unhappy with her failing love affair, her career, and even herself—decides to enroll her two Rhodesian ridgebacks into dog agility training. She's hoping to both find a hobby and straighten out her unruly pets, but she soon discovers that dog agility demands more from her than she ever expected. What follows is a life-changing experience: one that teaches her not only about her dogs but also about herself.

With Irina’s guidance and wisdom, Quinn and her dogs develop a deep bond of trust as they learn to navigate the course obstacles, and Quinn begins to accept her own flaws, allowing her to find the inner strength to become the "alpha dog” of her own life.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 26, 2011

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580054249

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use