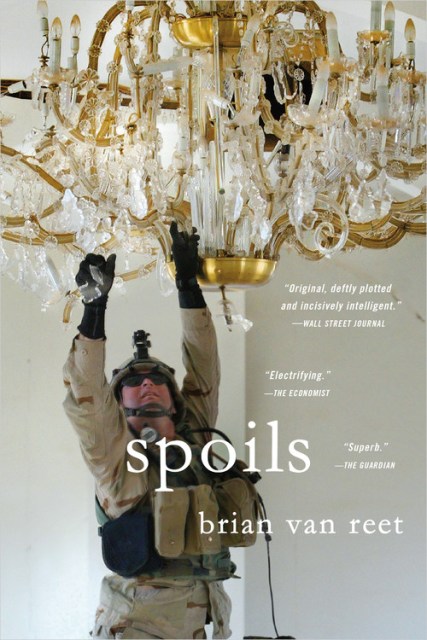

Spoils

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $8.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 24, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In dazzling and propulsive prose, Brian Van Reet explores the lives on both sides of the battle lines: Cassandra, a nineteen-year-old gunner on an American Humvee who is captured during a deadly firefight and awakens in a prison cell; Abu Al-Hool, a lifelong mujahedeen beset by a simmering crisis of conscience as he struggles against enemies from without and within, including the new wave of far more radicalized jihadists; and Specialist Sleed, a tank crewman who goes along with a “victimless” crime, the consequences of which are more awful than any he could have imagined.

Depicting a war spinning rapidly out of control, destined to become a modern classic, Spoils is an unsparing and morally complex novel that chronicles the achingly human cost of combat.

“The finest Iraq War novel yet written by an American”-Wall Street Journal, 10 Best Novels of the Year

“An electrifying debut” (The Economist) that maps the blurred lines between good and evil, soldier and civilian, victor and vanquished.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 24, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316316170

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use