Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

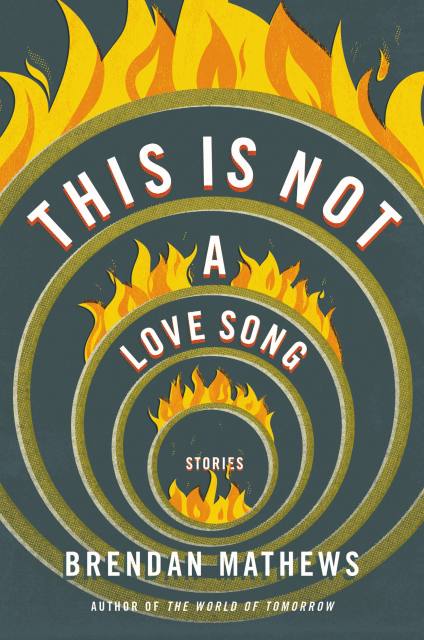

This Is Not a Love Song

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $34.00 $44.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A debut collection of moving and darkly witty stories from an “admirably fearless” (New York Times Book Review) writer whom critics have compared to Michael Chabon, E.L. Doctorow, and Dennis Lehane

A Massachusetts Book Award “Must Read” Selection

When marriages, friendships, and families come undone, to what lengths do we go to keep it all together? That question lies at the heart of Brendan Mathews’s buoyant and unforgettable debut story collection. A young mother watches as her desperate husband, convinced a hidden poison lurks inside their walls, tears their home apart. Two journalists bruised by romance and revolution, one a survivor of the Bosnian war, trade tales of lost lovers. A father and his sons haggle over the family business during a high-stakes round of golf. And a lovesick circus clown tries to explain the accidents that bound him to a trapeze artist and a witless lion tamer.

If Mathews’s novel The World of Tomorrow was an “outsized” entertainment, a “big, expressive debut” (Wall Street Journal), then This Is Not a Love Song, two stories from which have been included in The Best American Short Stories, is glorious proof that he excels equally as a miniaturist. From rock-star flameouts to church burnings to ordinary people trying not to fall out of love, these stories are packed with vivid detail, emotional precision, and deft, redemptive humor.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316382137

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use