Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

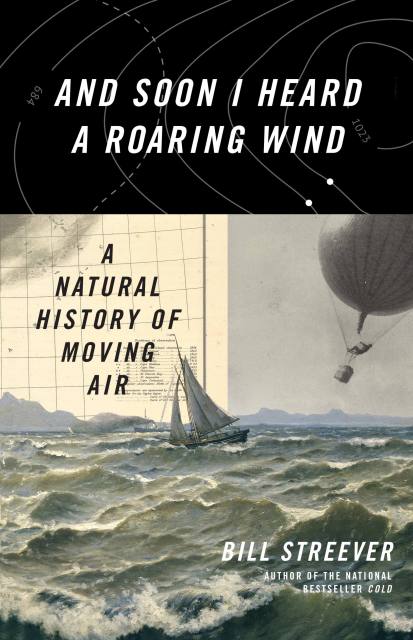

And Soon I Heard a Roaring Wind

A Natural History of Moving Air

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.00 $31.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 26, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A thrilling exploration of the science and history of wind from the bestselling author of Cold.

Scientist and bestselling nature writer Bill Streever goes to any extreme to explore wind — the winds that built empires, the storms that wreck them — by traveling right through it. Narrating from a fifty-year-old sailboat, Streever leads readers through the world’s first forecasts, Chaos Theory, and a future affected by climate change. Along the way, he shares stories of wind-riding spiders, wind-sculpted landscapes, wind-generated power, wind-tossed airplanes, and the uncomfortable interactions between wind and wars, drawing from natural science, history, business, travel, as well as from his own travels.

And Soon I Heard a Roaring Wind is an effortless personal narrative featuring the keen observations, scientific rigor, and whimsy that readers love. You’ll never see a breeze in the same light again.

Scientist and bestselling nature writer Bill Streever goes to any extreme to explore wind — the winds that built empires, the storms that wreck them — by traveling right through it. Narrating from a fifty-year-old sailboat, Streever leads readers through the world’s first forecasts, Chaos Theory, and a future affected by climate change. Along the way, he shares stories of wind-riding spiders, wind-sculpted landscapes, wind-generated power, wind-tossed airplanes, and the uncomfortable interactions between wind and wars, drawing from natural science, history, business, travel, as well as from his own travels.

And Soon I Heard a Roaring Wind is an effortless personal narrative featuring the keen observations, scientific rigor, and whimsy that readers love. You’ll never see a breeze in the same light again.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 26, 2016

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316410588

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use