Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

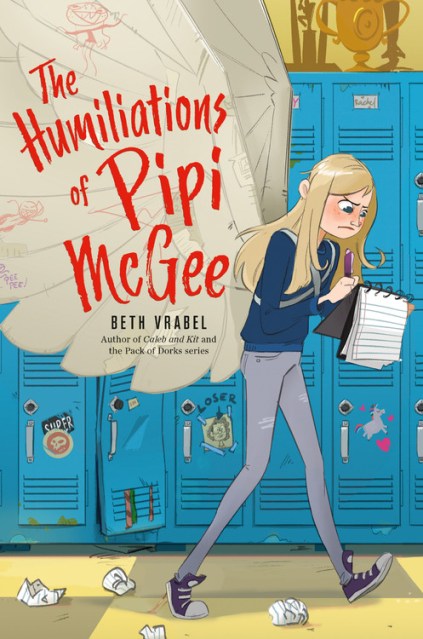

The Humiliations of Pipi McGee

Contributors

By Beth Vrabel

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 17, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Award-winning author Beth Vrabel writes with humor and empathy about a girl who wants to shed her embarrassing moments before she leaves middle school behind her. The first eight years of Penelope McGee’s education have been a curriculum in humiliation. Now she is on a quest for redemption, and a little bit of revenge.

From her kindergarten self-portrait as a bacon with boobs, to fourth grade when she peed her pants in the library thanks to a stuck zipper to seventh grade where…well, she doesn’t talk about seventh grade. Ever.

After hearing the guidance counselor lecturing them on how high school will be a clean slate for everyone, Pipi–fearing that her eight humiliations will follow her into the halls of Northbrook High School–decides to use her last year in middle school to right the wrongs of her early education and save other innocents from the same picked-on, laughed-at fate. Pipi McGee is seeking redemption, but she’ll take revenge, too.

From her kindergarten self-portrait as a bacon with boobs, to fourth grade when she peed her pants in the library thanks to a stuck zipper to seventh grade where…well, she doesn’t talk about seventh grade. Ever.

After hearing the guidance counselor lecturing them on how high school will be a clean slate for everyone, Pipi–fearing that her eight humiliations will follow her into the halls of Northbrook High School–decides to use her last year in middle school to right the wrongs of her early education and save other innocents from the same picked-on, laughed-at fate. Pipi McGee is seeking redemption, but she’ll take revenge, too.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 17, 2019

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press Kids

- ISBN-13

- 9780762493395

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use