Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

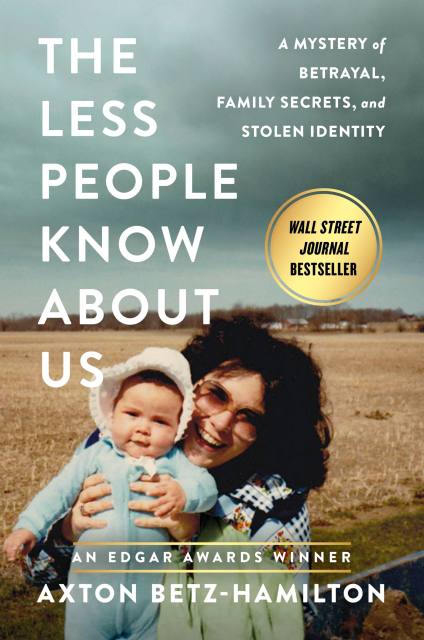

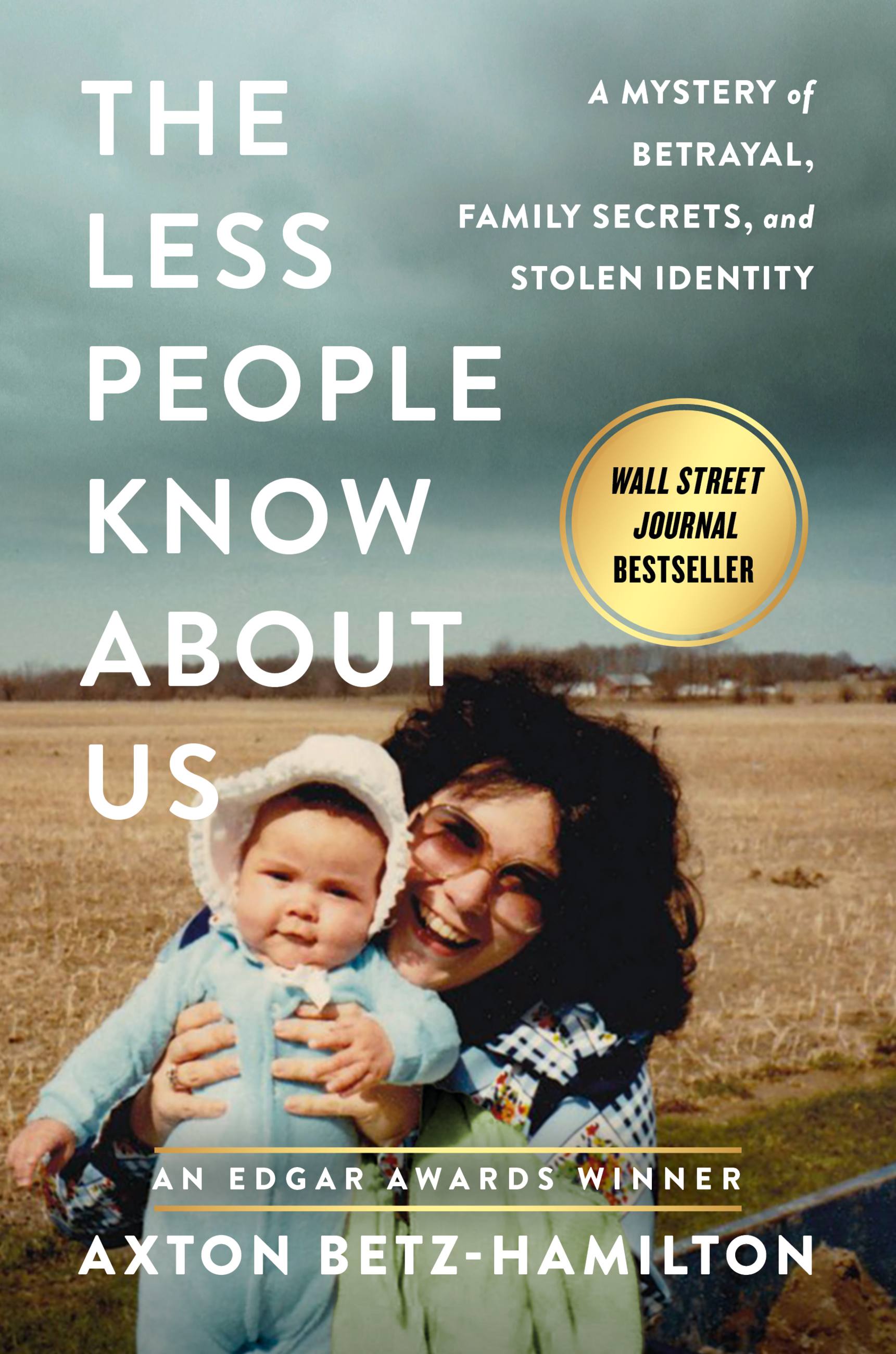

The Less People Know About Us

A Mystery of Betrayal, Family Secrets, and Stolen Identity

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$37.00Price

$47.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this powerful true crime memoir, an award-winning identity theft expert tells the shocking story of the duplicity and betrayal that inspired her career and nearly destroyed her family.

Axton Betz-Hamilton grew up in small-town Indiana in the early '90s. When she was 11 years old, her parents both had their identities stolen. Their credit ratings were ruined, and they were constantly fighting over money. This was before the age of the Internet, when identity theft became more commonplace, so authorities and banks were clueless and reluctant to help Axton's parents.

Axton's family changed all of their personal information and moved to different addresses, but the identity thief followed them wherever they went. Convinced that the thief had to be someone they knew, Axton and her parents completely cut off the outside world, isolating themselves from friends and family. Axton learned not to let anyone into the house without explicit permission, and once went as far as chasing a plumber off their property with a knife.

As a result, Axton spent her formative years crippled by anxiety, quarantined behind the closed curtains in her childhood home. She began starving herself at a young age in an effort to blend in–her appearance could be nothing short of perfect or she would be scolded by her mother, who had become paranoid and consumed by how others perceived the family.

As a result, Axton spent her formative years crippled by anxiety, quarantined behind the closed curtains in her childhood home. She began starving herself at a young age in an effort to blend in–her appearance could be nothing short of perfect or she would be scolded by her mother, who had become paranoid and consumed by how others perceived the family.

Years later, her parents' marriage still shaken from the theft, Axton discovered that she, too, had fallen prey to the identity thief, but by the time she realized, she was already thousands of dollars in debt and her credit was ruined.

The Less People Know About Us is Axton's attempt to untangle an intricate web of lies, and to understand why and how a loved one could have inflicted such pain. Axton will present a candid, shocking, and redemptive story and reveal her courageous effort to grapple with someone close that broke the unwritten rules of love, protection, and family.

Genre:

-

"Reads like a grim folk tale...intimate and engrossing."The New York Times

-

"The air of menace is palpable...A deeply compelling story of a crime that hit close to home."NPR

-

"The tension of a thriller...[and] jaw dropping revelations. Astonishing and disturbing, this emotionally resonant book is perfect for true crime fans."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"This memoir has all the suspense and twists of a thriller; even as readers begin to suspect the truth, it still shocks...highly recommended."Booklist

-

"Betz-Hamilton expertly blends true crime and memoir in this tale of family, lies, and identity...a brave, candid examination of her painful past [and] a poignant and fascinating exploration of identity theft."Library Journal

-

"'Identity theft' sounds like something that happens far, far away and only to other people...certainly not within a seemingly picture-perfect family in the rural U.S. In a gut-wrenching portrayal of victimization starting at age 11, Axton Betz-Hamilton shows that's simply not true. The stunning revelations will keep you looking over your shoulder for a long time and even more troubling...at the ones you think you know the best!"Nancy Grace, legal commentator, broadcast journalist, and New York Times bestselling author of The Eleventh Victim

-

"Axton Betz-Hamilton's story is remarkable. One of the primary challenges for those of us advocating for more rights and resources for identity theft victims is their reluctance to share their experience. Betz-Hamilton writes with candor and grace about both her relationship with her mother/perpetrator, and the long term effect victimization has had on her life."EvaCasey Velasquez, president/CEO of Identity Theft Resource Center

-

"A brave, rueful memoir of fear and heartbreak in rural America. Axton Betz-Hamilton mines the most essential of life's questions: can we ever really know the people we love? The Less People Know About Us is an unflinching portrait of grit and determination in the wake of a fractured childhood and complicated grief."Carolyn Murnick, author of The Hot One

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538730287

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use