Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

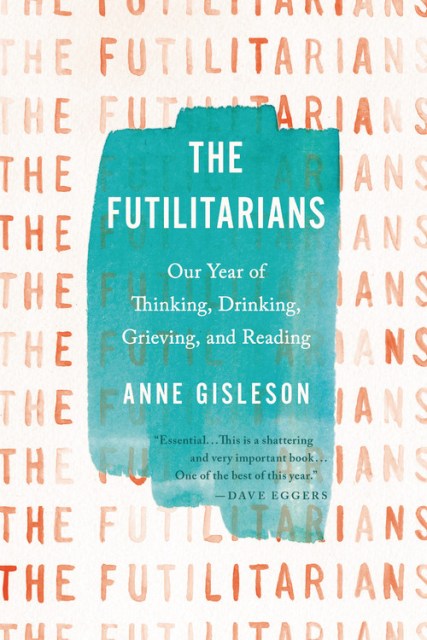

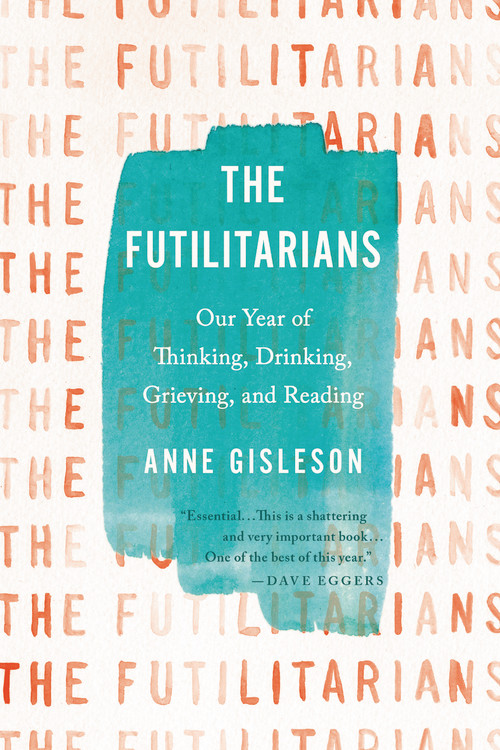

The Futilitarians

Our Year of Thinking, Drinking, Grieving, and Reading

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 31, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A memoir of friendship and literature chronicling a search for meaning and comfort in great books, and a beautiful path out of grief.

Anne Gisleson had lost her twin sisters, had been forced to flee her home during Hurricane Katrina, and had witnessed cancer take her beloved father. Before she met her husband, Brad, he had suffered his own trauma, losing his partner and the mother of his son to cancer in her young thirties. “How do we keep moving forward,” Anne asks, “amid all this loss and threat?” The answer: “We do it together.”

Anne and Brad, in the midst of forging their happiness, found that their friends had been suffering their own losses and crises as well: loved ones gone, rocky marriages, tricky child-rearing, jobs lost or gained, financial insecurities or unexpected windfalls. Together these resilient New Orleanians formed what they called the Existential Crisis Reading Group, which they jokingly dubbed “The Futilitarians.” From Epicurus to Tolstoy, from Cheever to Amis to Lispector, each month they read and talked about identity, parenting, love, mortality, and life in post-Katrina New Orleans,

In the year after her father’s death, these living-room gatherings provided a sustenance Anne craved, fortifying her and helping her blaze a trail out of her well-worn grief. More than that, this fellowship allowed her finally to commune with her sisters on the page, and to tell the story of her family that had remained long untold. Written with wisdom, soul, and a playful sense of humor, The Futilitarians is a guide to living curiously and fully, and a testament to the way that even from the toughest soil of sorrow, beauty and wonder can bloom.

Anne Gisleson had lost her twin sisters, had been forced to flee her home during Hurricane Katrina, and had witnessed cancer take her beloved father. Before she met her husband, Brad, he had suffered his own trauma, losing his partner and the mother of his son to cancer in her young thirties. “How do we keep moving forward,” Anne asks, “amid all this loss and threat?” The answer: “We do it together.”

Anne and Brad, in the midst of forging their happiness, found that their friends had been suffering their own losses and crises as well: loved ones gone, rocky marriages, tricky child-rearing, jobs lost or gained, financial insecurities or unexpected windfalls. Together these resilient New Orleanians formed what they called the Existential Crisis Reading Group, which they jokingly dubbed “The Futilitarians.” From Epicurus to Tolstoy, from Cheever to Amis to Lispector, each month they read and talked about identity, parenting, love, mortality, and life in post-Katrina New Orleans,

In the year after her father’s death, these living-room gatherings provided a sustenance Anne craved, fortifying her and helping her blaze a trail out of her well-worn grief. More than that, this fellowship allowed her finally to commune with her sisters on the page, and to tell the story of her family that had remained long untold. Written with wisdom, soul, and a playful sense of humor, The Futilitarians is a guide to living curiously and fully, and a testament to the way that even from the toughest soil of sorrow, beauty and wonder can bloom.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 31, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316393928

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use