Promotion

Use code BESTBOOKS24 for 25% off sitewide + free shipping over $35

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

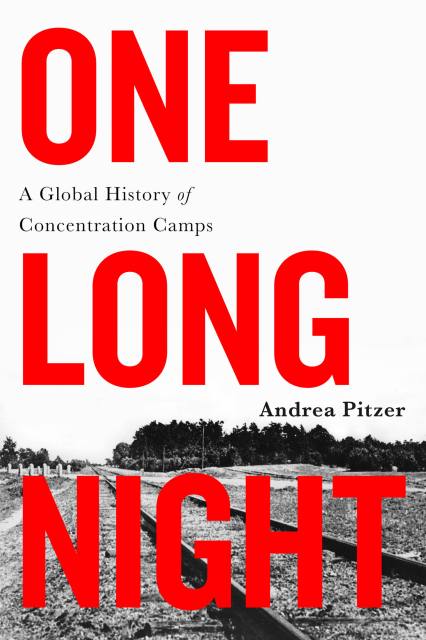

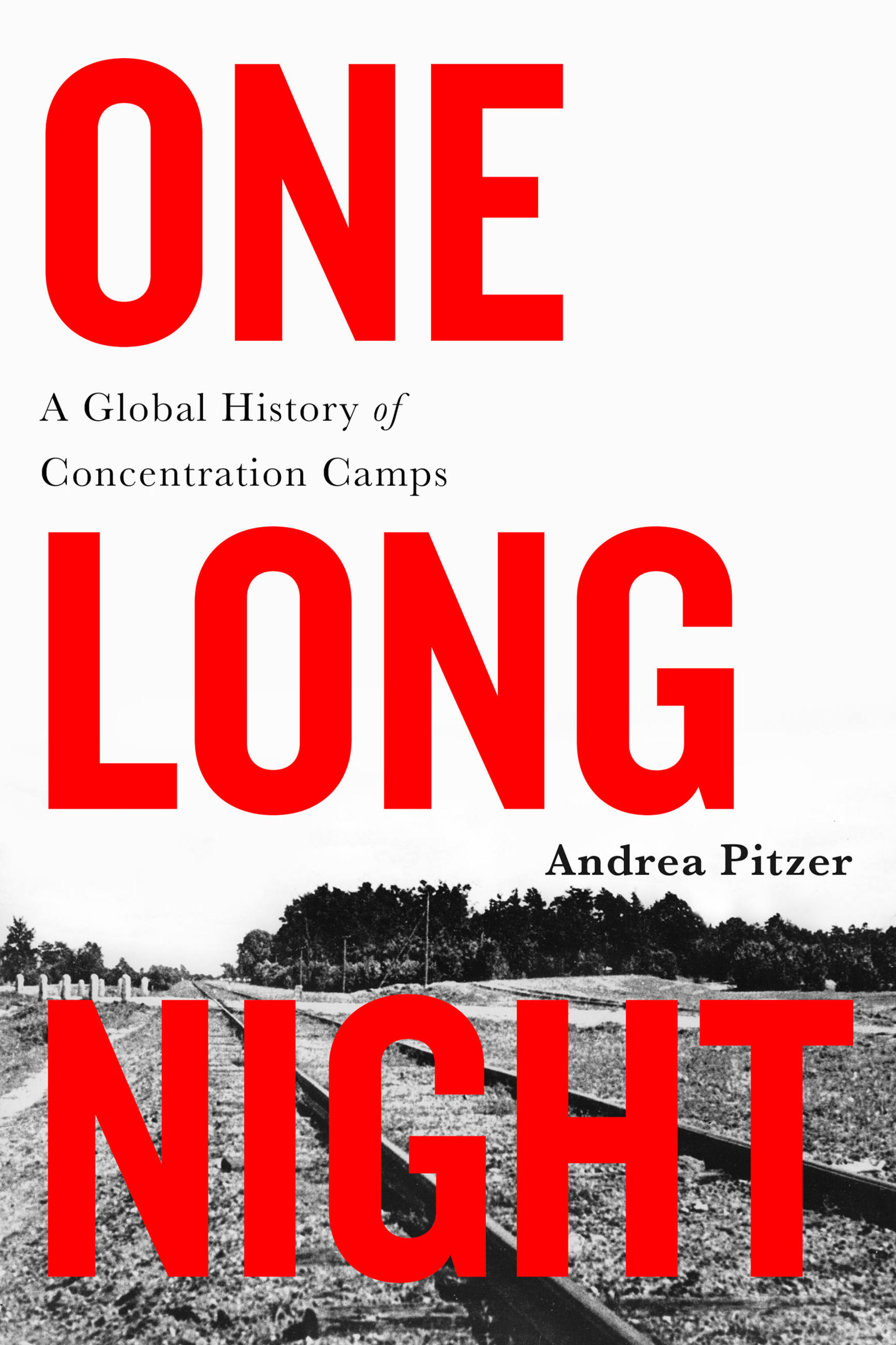

One Long Night

A Global History of Concentration Camps

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 19, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

For over 100 years, at least one concentration camp has existed somewhere on Earth. First used as battlefield strategy, camps have evolved with each passing decade, in the scope of their effects and the savage practicality with which governments have employed them. Even in the twenty-first century, as we continue to reckon with the magnitude and horror of the Holocaust, history tells us we have broken our own solemn promise of “never again.”

In this harrowing work based on archival records and interviews during travel to four continents, Andrea Pitzer reveals for the first time the chronological and geopolitical history of concentration camps. Beginning with 1890s Cuba, she pinpoints concentration camps around the world and across decades. From the Philippines and Southern Africa in the early twentieth century to the Soviet Gulag and detention camps in China and North Korea during the Cold War, camp systems have been used as tools for civilian relocation and political repression. Often justified as a measure to protect a nation, or even the interned groups themselves, camps have instead served as brutal and dehumanizing sites that have claimed the lives of millions.

Drawing from exclusive testimony, landmark historical scholarship, and stunning research, Andrea Pitzer unearths the roots of this appalling phenomenon, exploring and exposing the staggering toll of the camps: our greatest atrocities, the extraordinary survivors, and even the intimate, quiet moments that have also been part of camp life during the past century.

“Masterly”-The New Yorker

A Smithsonian Magazine Best History Book of the Year

-

As discussed on "All In with Chris Hayes"

-

"A disturbing yet important work on a universal calamity of the modern era...consistently fascinating."Star Tribune

-

"Drawing on memoirs, histories, and archival sources, [Pitzer] offers a chilling, well-documented history of the camps' development.... A potent, powerful history of cruelty and dehumanization."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"One Long Night is a don't-look-away narrative of concentration camps, a fearless and elegant tale of human cruelty but also of human courage. And it's told with such undaunted moral clarity, that the story serves to remind all of us that it is never too late to stand up for what is right."Deborah Blum, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of The Poisoner's Handbook

-

"Andrea Pitzer has a poet's grace and a documentarian's breadth, along with the curiosity of a reporter whose shoe leather has long ago frayed. In One Long Night, she also proves her rare ability to translate a century of suffering into a groundbreaking narrative that is fluid, lucid, and throbbing with humanity's ache. It will make you see the past - and the present - anew."Beth Macy, author of Truevine and Factory Man

-

"A clear-eyed and powerful exposure of the horrors of concentration camps, not just the ones we know about but the ones we've overlooked or ignored. The lengths Andrea Pitzer went to research and report this book prove revelatory."Annie Jacobsen, author of the Pulitzer Prize finalist The Pentagon's Brain

-

"Andrea Pitzer's searing One Long Night proceeds like an epic poem charged with the horror of concentration camps on six continents. It is a tale full of sound and fury, unfortunately signifying plenty. 'Old camps reopen, new ones are born,' Pitzer tells us in her clean prose that is cogent, passionate, profound, and profoundly disturbing."Peter Davis, Academy Award winner for Hearts and Minds, and author of the novel Girl of My Dreams

-

"In this engrossing history, Pitzer traces the origins of concentration camps and follows their development over more than a century.... Pitzer excels at focusing this sprawling history on the personal level."Publishers Weekly

-

Praise for The Secret History of Vladimir NabokovBooklist (starred review)

"A penetrating analysis certain to compel a major reassessment of the Nabokov canon." -

"A brilliant examination that adds to the understanding of an inspiring & enigmatic life."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"[Pitzer] has done much exemplary primary research, and this book forces one to consider several fascinating quandaries presented by Lolita and Pale Fire."The New York Review of Books

-

"Pitzer, like Nabokov, is a beautiful writer and gimlet-eyed observer, especially about her subject."The Boston Globe

-

"An illuminating book for confusing times"Sarah Rothbard, Zocalo

- On Sale

- Sep 19, 2017

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316303583

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use