By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

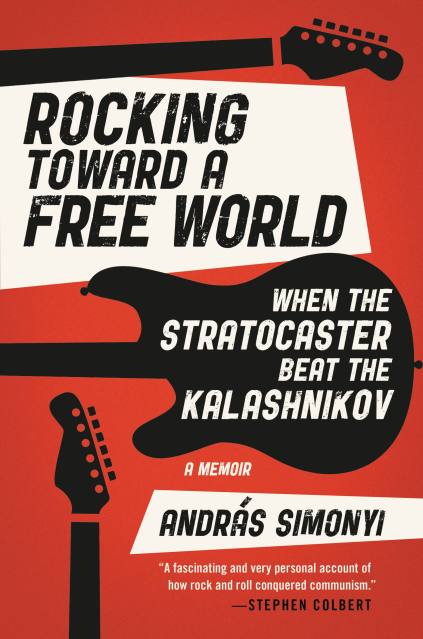

Rocking Toward a Free World

When the Stratocaster Beat the Kalashnikov

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 4, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538762233

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 4, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From renowned diplomat and musician András Simonyi — whom Stephen Colbert calls “the only ambassador I know who can shred a mean guitar!” — comes a timely and revealing memoir about growing up behind the Iron Curtain and longing for freedom while chasing the great power of rock and roll.

In ROCKING TOWARD A FREE WORLD, Simonyi charts the struggle of growing up in 1960s Hungary, a world in which listening to his favorite music was a powerful but furtive endeavor: records were black-market bootlegs; concerts were held under strict control, even banned; protests were folded into song lyrics. Get caught listening to Western radio could mean punishment, maybe prison. That didn’t matter to Simonyi, who from an early age felt the tremendous pull of rock and roll, the lure of American popular culture, and a burning desire to buck the system. Inspired by the protest music coming out of the West, he formed a band and became part of Hungary’s burgeoning rock scene. Then came the setbacks: tightening of control by the state, the seemingly inescapable weight of an authoritarian system, and the collapse of Simonyi’s own dreams of stardom.

A story of youth, rebellion, and hope, ROCKING TOWARD A FREE WORLD sheds new light on two of the most powerful forces of the modern age: global democracy and rock and roll. Deeply vital and compelling, Simonyi’s memoir chronicles how one man’s tremendous connection to American and British popular music inspired him to make a difference in his country and, eventually, the world. It tells the story of a generation, as played out in song lyrics and guitar riffs.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use