By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

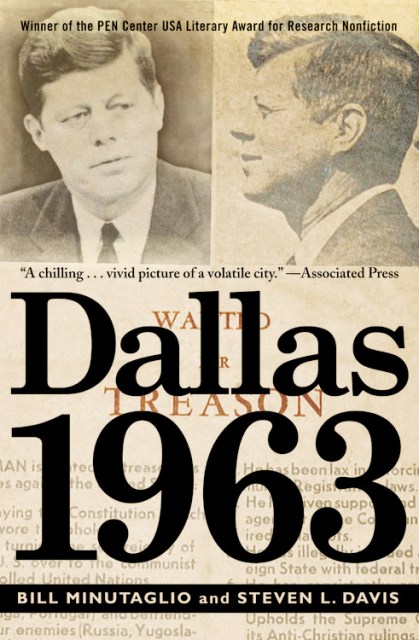

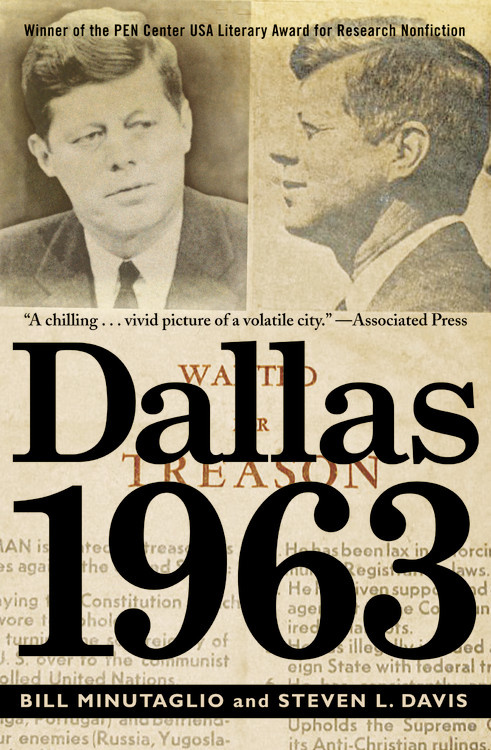

Dallas 1963

Contributors

By Steven L. Davis

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 21, 2014

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455522101

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 21, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis ingeniously explore the swirling forces that led many people to warn President Kennedy to avoid Dallas on his fateful trip to Texas. Breathtakingly paced, Dallas 1963 presents a clear, cinematic, and revelatory look at the shocking tragedy that transformed America. Countless authors have attempted to explain the assassination, but no one has ever bothered to explain Dallas-until now.

With spellbinding storytelling, Minutaglio and Davis lead us through intimate glimpses of the Kennedy family and the machinations of the Kennedy White House, to the obsessed men in Dallas who concocted the climate of hatred that led many to blame the city for the president’s death. Here at long last is an accurate understanding of what happened in the weeks and months leading to John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Dallas 1963 is not only a fresh look at a momentous national tragedy but a sobering reminder of how radical, polarizing ideologies can poison a city-and a nation.

Winner of the PEN Center USA Literary Award for Research Nonfiction

Named one of the Top 3 JFK Books by Parade Magazine.

Named 1 of The 5 Essential Kennedy assassination books ever written by The Daily Beast.

Named one of the Top Nonfiction Books of 2013 by Kirkus Reviews.

-

"Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis's DALLAS 1963 is a brilliantly written, haunting eulogy to John F. Kennedy. By exposing the hatred aimed at our 35th president, the authors demonstrates that America--not just Lee Harvey Oswald--was ultimately responsible for his death. Every page is an eye opener. Highly recommended!"Douglas Brinkley, professor of history at Rice University and author of Cronkite

-

"All the great personalities of Dallas during the assassination come alive in this superb rendering of a city on a roller coaster into disaster. History has been waiting fifty years for this book."Lawrence Wright, author of The Looming Tower and Going Clear

-

"Minutaglio and Davis capture in fascinating detail the creepiness that shamed Dallas in 1963."Gary Cartwright, author and contributing editor at Texas Monthly

-

"In this harrowing, masterfully-paced depiction of a disaster waiting to happen, Minutaglio and Davis examine a prominent American city in its now-infamous moment of temporary insanity. Because those days of partisan derangement look all too familiar today, DALLAS 1963 isn't just a gripping narrative-it's also a somber cautionary tale."Robert Draper, contributor, New York Times Magazine and author of Do Not Ask What Good We Do: Inside the U.S. House of Representatives

-

"The authors skillfully marry a narrative of the lead-up to the fateful day with portrayals of the Dixiecrats, homophobes, John Birchers, hate-radio spielers, and the 'superpatriots' who were symptomatic of the paranoid tendency in American politics."Harold Evans, author of The American Century

-

"After fifty years, it's a challenge to fashion a new lens with which to view the tragic events of November 22, 1963--yet Texans [Minutaglio and Davis] pull it off brilliantly."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Chilling... The authors make a compelling, tacit parallel to today's running threats by extremist groups."Kirkus

-

"A thoughtful look at the political and social environment that existed in Dallas at the time of the president's election... a climate, the authors persuasively argue, of unprecedented turmoil and hatred."Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use