By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

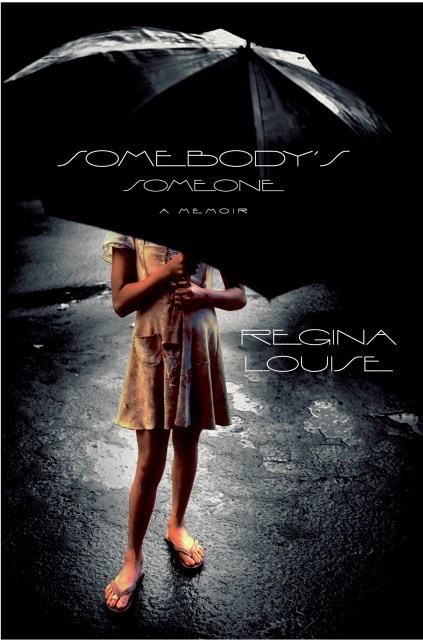

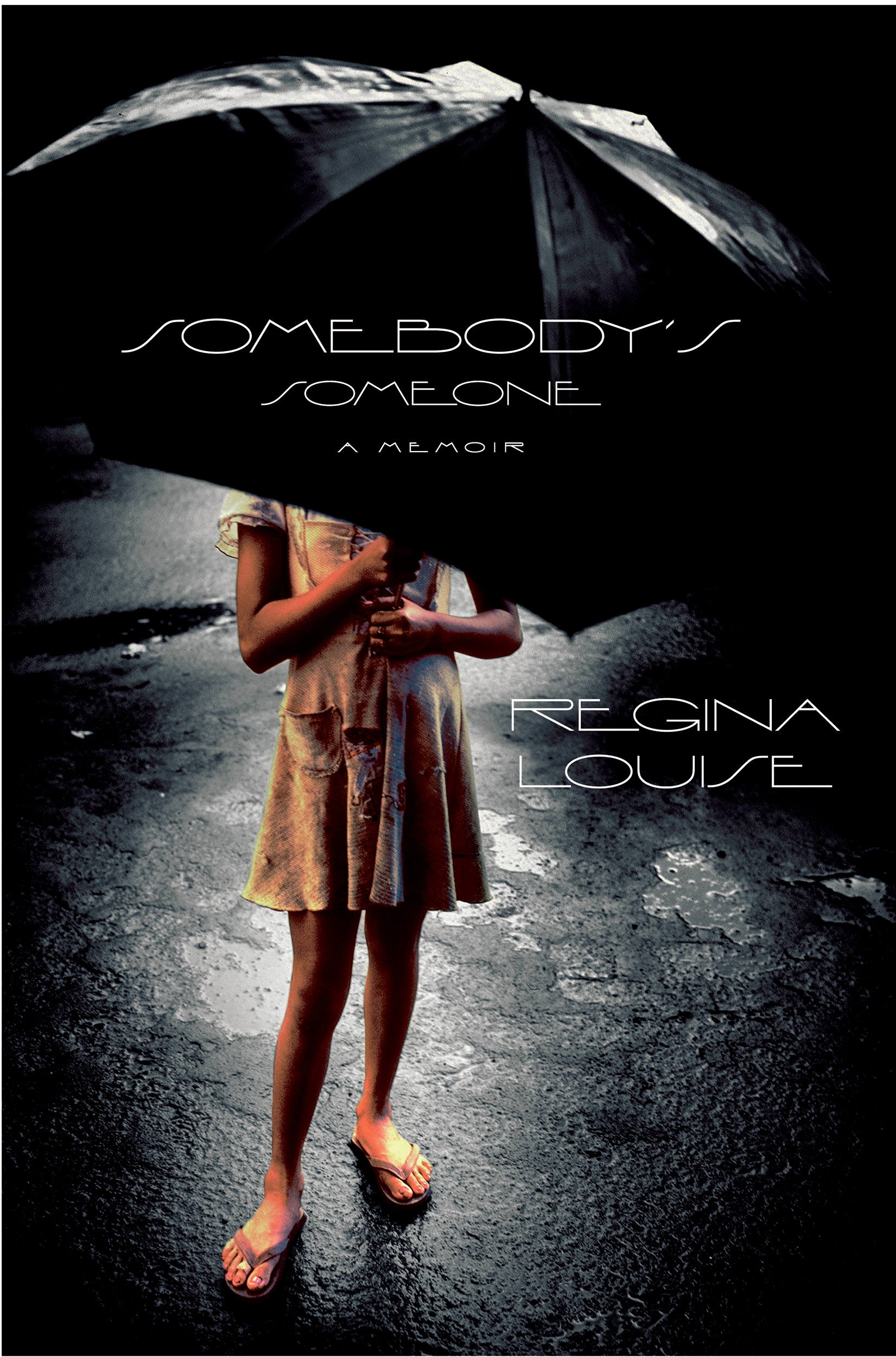

Somebody’s Someone

A Memoir

Contributors

By Regina Louise

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 28, 2009

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446556330

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $10.99 $13.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 28, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

What happens to a child when her own parents reject her and sit idly by as others abuse her? In this poignant, heart wrenching debut work, Regina Louise recounts her childhood search for someone to feel connected to. A mother she has never known–but long fantasized about– deposited her and her half sister at the same group home that she herself fled years before. When another resident beats Regina so badly that she can barely move, she knows that she must leave this terrible place-the only home she knows.

Thus begins Regina’s fight to survive, utterly alone at the age of 10. A stint living with her mother and her abusive boyfriend is followed by a stay with her father’s lily white wife and daughters, who ignore her before turning to abuse and ultimately kicking her out of the house. Regina then tries everything in her search for someone to care for her and to care about, from taking herself to jail to escaping countless foster homes to be near her beloved counselor. Written in her distinctive and unique voice, Regina’s story offers an in-depth look at the life of a child who no one wanted. From her initial flight to her eventual discovery of love, your heart will go out to Regina’s younger self, and you’ll cheer her on as she struggles to be Somebody’s Someone.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use