Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

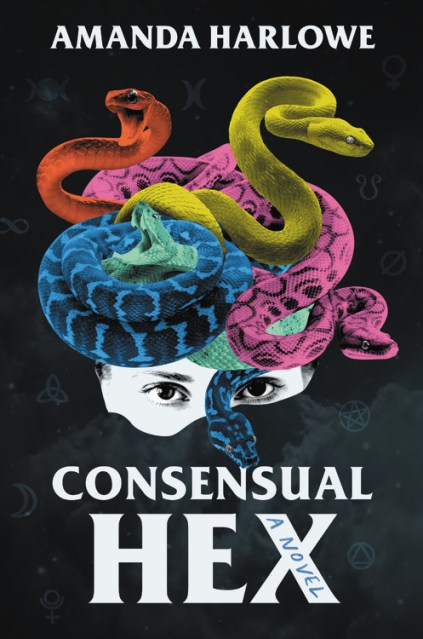

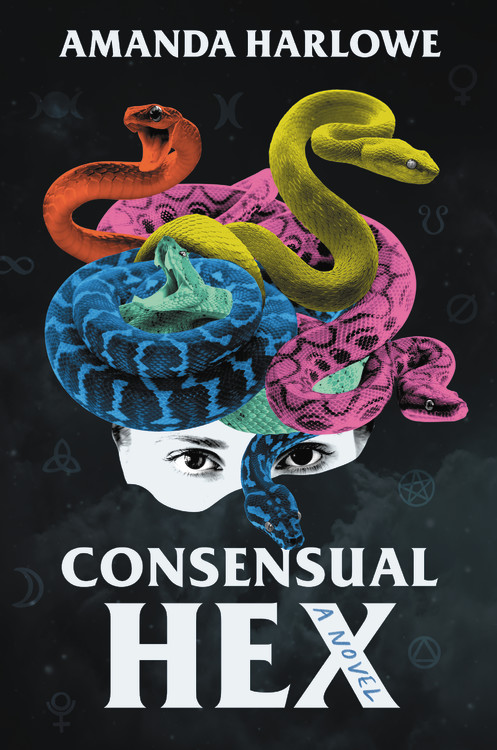

Consensual Hex

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 6, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Lee, a first year at Smith, is raped under eerie circumstances during orientation week by an Amherst frat boy, she’s quickly disillusioned by her lack of recourse. As her trauma boils within her, Lee is selected for an exclusive seminar on Gender, Power, and Witchcraft, where she meets Luna (an alluring Brooklyn hipster), Gabi (who has a laundry list of phobias), and Charlotte (a waifish, chill international student). Granted a charter for a coven and suddenly in possession of real magic, the four girls are tasked by their aloof Professor with covertly retrieving a grimoire that an Amherst fraternity has gotten their hands on. But when the witches realize the frat brothers are using magic to commit and cover up sexual assault all over Northampton, their exploits escalate into vigilante justice. As Lee’s thirst for revenge on her rapist grows, things spiral out of control, pitting witch against witch as they must wrestle with how far one is willing to go to heal.

Consensual Hex is both a gripping page-turner and a sensitive portrait of a young woman coming of age, uncovering the ways in which love and obsession and looking to fit in can go hand in hand. Lee, an outstanding, magical anti-heroine, refuses to be pigeonholed as a model victim or a horrific example. Instead, her caustic voice demands our attention, clawing out from every page, equally vicious and vulnerable as she lures us, then dares us, to transgress. Dark, biting, and archly camp, Consensual Hex announces Harlowe as a significant talent.

Consensual Hex is both a gripping page-turner and a sensitive portrait of a young woman coming of age, uncovering the ways in which love and obsession and looking to fit in can go hand in hand. Lee, an outstanding, magical anti-heroine, refuses to be pigeonholed as a model victim or a horrific example. Instead, her caustic voice demands our attention, clawing out from every page, equally vicious and vulnerable as she lures us, then dares us, to transgress. Dark, biting, and archly camp, Consensual Hex announces Harlowe as a significant talent.

Genre:

-

"An intense, unflinching, and supernatural coming-of-age tale."Kirkus

-

"A story told with great verve and panache! A gripping study of revenge, justice, and the perils of attempting to deliver either."Paula Brackston, New York Times bestselling author of The Witch's Daughter

-

"Gloriously angry and deliciously weird, Consensual Hex is oh-so satisfying - a tale of rage and revenge that's delivered with both heart and savage wit. Darker than a midnight sky on a new moon - I devoured it in a single, breathless gulp."Katie Lowe, author of The Furies

-

"A rapturous, riotous novel that I loved as much for its daring ingenuity as for its big brassy heart."Caroline Zancan, author of We Wish You Luck

-

"Smart, edgy, ghoulishly gripping, fiercely political, and radically funny, every Lit major with a candle on her altar and feminist vengeance in her heart needs to read this book."Amanda Yates Garcia, author of Initiated: Memoir of a Witch

- On Sale

- Oct 6, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538752203

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use