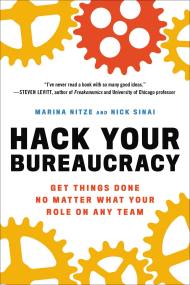

Credible

The Power of Expert Leaders

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 11, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Amanda Goodall has spent a decade researching what makes organizations tick, everywhere from the business world to hospitals and healthcare systems, football and basketball teams, and Formula 1 organizations. By debunking the cult of managerialism (the notion that smart people can run anything and the emphasis on leadership personality), Goodall reshapes our understanding of bosses and the traits necessary for organizational success. She identifies the key characteristics of expert leaders and provides a real and grossly underappreciated model for career success: "go deep into a business, work hard, pay attention, and know your stuff." Those who run hospitals and healthcare systems, for example, should be physicians with deep clinical expertise, not financiers or people parachuted in from other industries. Those who run school systems and universities need to understand from experience the stress of balancing teaching, research, and student welfare

Credible demonstrates categorically that expertise matters more than ever and that we need our leaders to be experts with a deep, understanding of their organizations from many years spent learning the business and working their way up the ladder. The people who work for them are happier because they feel better understood and the organizations they lead are more successful.

-

“[A] cogent treatise…The stories of corporate and political folly enrage, and the case for how organizations can promote and reward expertise by fostering ‘informed dissent’ and granting line managers ‘freedom and responsibility’ is well made. This spirited defense of specialists convinces.”Publishers Weekly

-

“A persuasive argument about the need for expertise in leaders… Citing many examples in areas such as health care, manufacturing, sports, and technology, Goodall has found that expert leadership leads to success … Well-grounded arguments for effective leadership.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“This book presents many enlightening instances of the successes of companies with expert leaders and the failures of companies with generalist managers who had little or no knowledge of, nor experience with, their company's core business. A convincing argument that a company's success requires leaders to have specific industry expertise.”Library Journal

-

“Engaging and powerful. Groups must have leaders, and these leaders must have deep knowledge about the group’s core mission. With many vivid examples from a range of industries and settings, Amanda Goodall shows how leadership and expertise must be reflected within both for-profit and not-for-profit firms.”Nicholas Christakis, Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science, Yale University

-

“An extremely convincing analysis of the crucial importance of expert leaders, supported by many fascinating on-the-ground stories. Goodall’s work will be the go-to landmark guide for the best leaders not just in my own field of health care but for every organization, from banks to basketball teams.”Major-General Marc Bilodeau, surgeon general, Canadian Armed Forces

-

“In her clear and invigorating book, Goodall lays out an essential message for our times: the very best leaders are those who are experts in what they are leading. If you’ve had nagging suspicions about the idea of generalist, all-purpose leaders, this well-researched book will validate your concerns. If you’re currently a leader, aspire to be a leader, or are responsible for selecting and assessing leaders, Credible is a must-read.”Donald C. Hambrick, Evan Pugh University Professor, Penn State University

-

“Based on years of renowned research, Credible convincingly demonstrates the superiority of organizations led by experts. A must-read for everyone interested in improving leadership in any type of commercial or public organization.”Marcel Levi, former chairman and chief executive, University College London Hospitals

-

“Credible provides fascinating insight into the amount and kind of expertise required by leaders. Anyone in a senior leadership position should read this book and consider the implications for their own performance.”Lord Gus O’Donnell, former head of the UK Civil Service and Permanent Secretary of the UK Treasury

-

“Credible offers conclusive proof that leaders with expert knowledge of their company’s product and methods make more informed and better decisions.”Keith Griffiths, chairman and global principal designer, Aedas

- On Sale

- Jul 11, 2023

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541702509

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use