Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Perfect Store, The

Inside eBay

Contributors

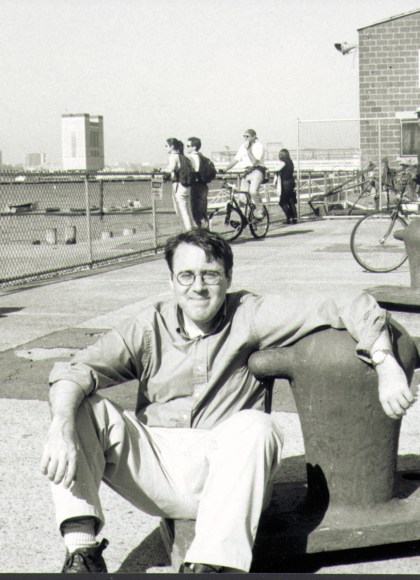

By Adam Cohen

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 14, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Pierre Omidyar launched a clunky website from a spare bedroom over Labor Day weekend of 1995, he wanted to see if he could use the Internet to create a perfect market. He never guessed his old-computer parts and Beanie Baby exchange would revolutionize the world of commerce.

Now, Adam Cohen, the only journalist ever to get full access to the company, tells the remarkable story of eBay’s rise. He describes how eBay built the most passionate community ever to form in cyberspace and forged a business that triumphed over larger, better-funded rivals. And he explores the ever-widening array of enlistees in the eBay revolution, from a stay-at-home mom who had to rent a warehouse for her thriving business selling bubble-wrap on eBay to the young MBA who started eBay Motors (which within months of its launch was on track to sell $1 billion in cars a year), to collectors nervously bidding thousands of dollars on antique clothing-irons.

Adam Cohen’s fascinating look inside eBay is essential reading for anyone trying to figure out what’s next. If you want to truly understand the Internet economy, The Perfect Store is indispensable.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 14, 2008

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316054645

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use