The Earth is Fat in Fall

In Earth Almanac, noted nature writer Ted Williams invites readers to reflect on fleeting moments of the natural world throughout the year.

He says: “Writing about experiences afield is a way of reliving them. I get to do it all twice. I have always seen the essays in Earth Almanac as a chance to take a breather, chill out, count inventory, and, especially, enjoy.” We hope you enjoy this meditation on the magic of the early fall.

The earth is fat in fall, dripping milk and honey into the mouths of wild creatures and into the souls of humans, who will soon be entering their own form of hibernation in front of flickering fires and flickering screens.

Eyes South

Throughout most of the United States, buckeye butterflies are wafting south, sometimes in concentrations that rival the famous fall migration of monarchs. Look for these midsize butterflies in clearings and along meadow edges as they fuel up on the nectar of asters and other late-blooming wildflowers. Often they’ll be perched on a protruding branch or the ground. If another insect passes close by, they’re likely to give chase, then return to their posts. The six striking, multicolored eye spots — two on each hindwing and one on each forewing — are thought to frighten insectivorous birds.

Adults live for only about ten days, but butterflies of the last brood can overwinter if they make it to southern states and countries. In spring buckeyes breed themselves back to their summer habitat, rolling north in waves of successive generations.

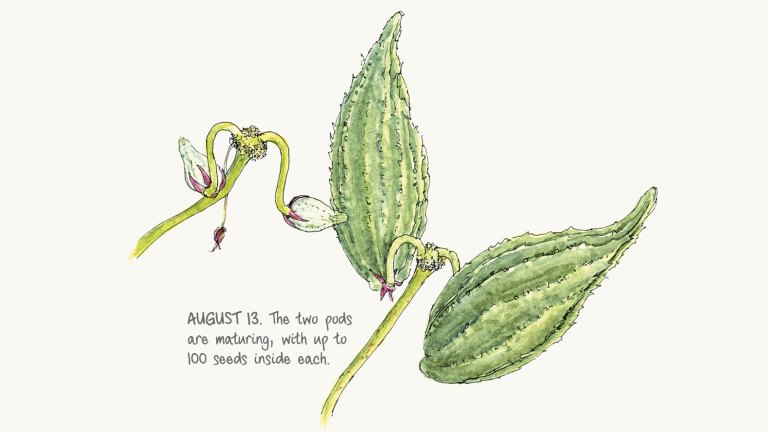

Explosive Jewels

In autumn roadsides and meadow edges from Newfoundland to Saskatchewan and Florida to Nebraska explode in color as the orange, slipper-shaped blossoms of spotted jewelweed unfurl. Soon thereafter the ripe seedpods literally explode when jostled by beast or wind, sending seeds flying

in all directions — hence the plant’s alternate name “touchmenot.” The azure seeds, which taste like butternuts, were 189 eaten by various indigenous tribes, and they’re relished by birds and small mammals. When white-footed mice hoard them they stain their bellies blue.

The name “jewelweed” derives from the water-repellent quality of the leaves that causes dew and rain to bead up and sparkle in the sun. If you’re afflicted by poison ivy, poison oak, or athlete’s foot, dramatic relief can often be had by crushing the stems and applying the sticky paste to affected areas. At times jewelweed can be invasive in gardens, but in dismissing it as a “dreadful weed nuisance” the New York Times elicited the ire of biology professor Mary Leck of Rider University in Lawrenceville, New Jersey. After citing all the above attributes of this remarkable plant, she offered this: “On reflection, perhaps jewelweed is truly a potential deterrent to the gardener — it may offer too many distractions from gardening chores.”

Enjoy season-by-season essays like these in Earth Almanac: A Year of Witnessing the Wild, from the Call of the Loon to the Journey of the Gray Whale.

Excerpted and adapted from Earth Almanac © Ted Williams.