The Soil Food Web: A Gardener’s Best Friend

Step away from the rototiller! Tilling destroys the organisms that make up the soil food web and are essential to healthy, living earth.

If you’re like me, you love gardening for the beauty and food it produces and for the sheer pleasure of being outside and watching stuff happen. This is a process we can do instinctively, often with great success. But my enjoyment of gardening increased dramatically once I learned more about the science of soil — the life in my dirt and on the plants growing in it.

Scientists (and gardeners!) are only beginning to understand the world of soil biology. What we’ve learned is this: everything we’ve been doing is wrong. (It’s a lot like child rearing, that way.)

Okay, not everything. Many well-intentioned organic gardeners, though, have been rototilling once or twice a year, mistakenly believing that chopping and mixing in weeds and other organic matter will fluff, aerate, and improve the soil. Once upon a time, I, too, itched to till those nice grasses and weeds into my garden soil.

Then I went over to the “dark side” — dark as in rich, dark, carbon-filled soil.

We now know that tilling damages the soil instead of improving it, in part by breaking up soil particles and turning them into dust.

Imagine pouring water through a colander full of Cheerios; the water wets the Cheerios and drains right through. Now imagine first grinding Cheerios to the consistency of flour, putting the flour in the colander, and pouring water over it. The result is glop, right? That’s what a rototiller does to soil.

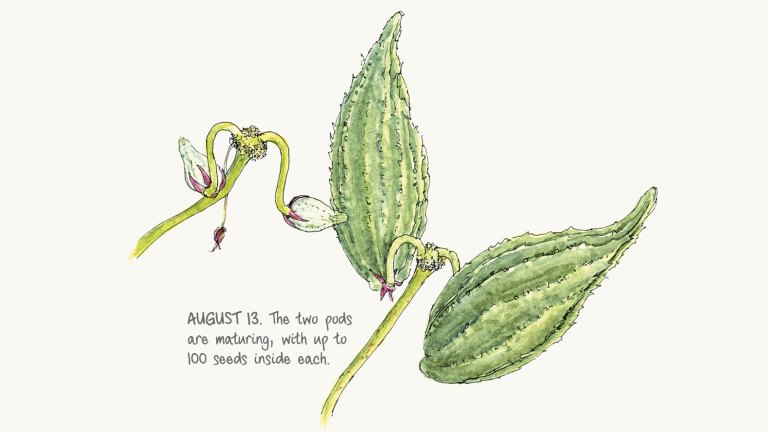

Rototilling also kills or removes lots of things that you want to live in your soil. Healthy soil needs water, organic matter, and to be pretty much left alone, so the life we want can flourish there. That life puts the “crumb” in “crumbly soil.” We want it there because it’s part of a long, long food chain — the food soil web.

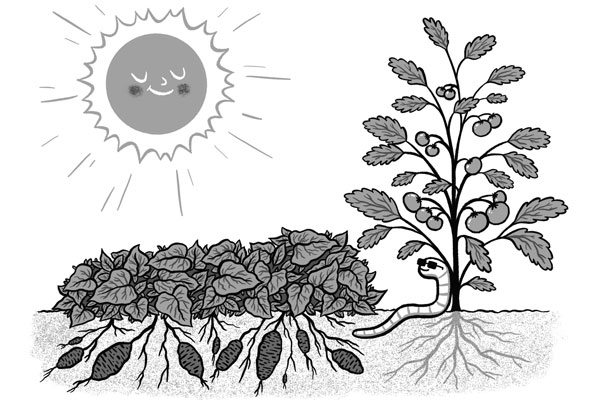

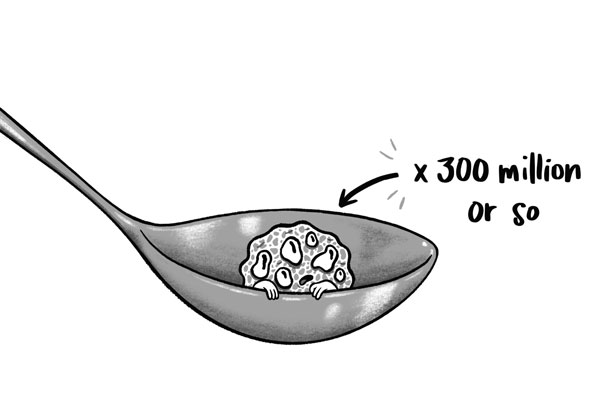

Really good soil, the stuff organic gardeners drool over, contains a lot of life. A teaspoon of good soil contains more microbes than there are people in the United States. Plus, good soil holds organic matter and arthropods, worms, and other crawly things that keep the whole wonderful mess alive, crumbly, and nourishing to plant life.

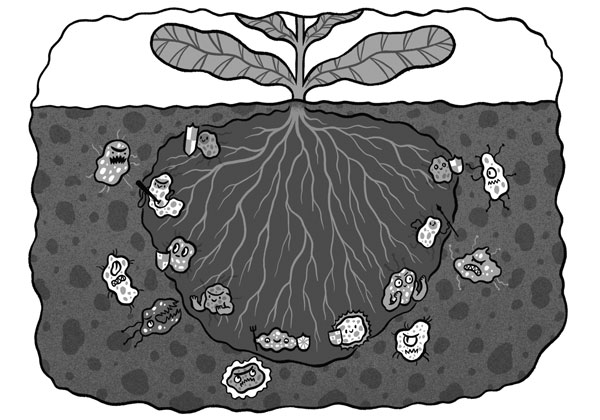

Together, the members of the soil food web keep the planet running by growing plants. Like little microscopic sponges, microbes and their soil food web friends make aggregates, or crumbs — clusters of soil particles that absorb water and create air spaces in soil. Soil aggregates, along with plant roots, hold water in the soil and also allow it to infiltrate and absorb into deeper ground, thereby preventing flooding and erosion.

The soil food web cycles nutrients, eating or decomposing other living things and turning them into fertilizer plants can absorb. And it suppresses disease; all organisms “eat or compete” — that is, eat other organisms or compete with them for the food supply. A large and varied population of soil life keeps the bad guys from taking over.

This food web also pulls carbon out of the air, keeping it in the soil in the form of humus, which is the long chain of carbon molecules that makes rich soil dark. Humus is the end product of organic matter that has been serially digested by various soil residents; it holds water and functions as a sort of carbon condo for water, air, microbes, and nutrients, which are then available to plant roots.

Tilling disrupts the soil food web by chopping up those worms and fungal strands, exposing organisms to air and heat, and letting soil carbon combine with oxygen to form carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas we’re trying to make less of so we have a habitable planet to give to our grandchildren.

The more dry, exposed, and “fluffed up” your soil is, the less hospitable it is to life — including worms, germs, and your arugula.

Tilling in organic matter is a good thing for bad soil, but think of this as a rare or one-time event. If the soil you’re starting with is compacted, graded, or generally lacking biological activity, tilling can start it on the road to health. Once soil is loosened, though, we need to foster and conserve soil life and let nature go to work.

EXCERPTED FROM GROW YOUR SOIL! © BY DIANE MIESSLER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Growing awareness of the importance of soil health means that microbes are on the minds of even the most casual gardeners. After all, anyone who has ever attempted to plant a thriving patch of flowers or vegetables knows that what you grow is only as good as the soil you grow it in. It is possible to create and maintain rich, dark, crumbly soil that’s teeming with life, using very few inputs and a no-till, no-fertilizer approach. Certified permaculture designer and lifelong gardener Diane Miessler presents the science of soil health in an engaging, entertaining voice geared for the backyard grower. She shares the techniques she has used — including cover crops, constant mulching, and a simple-but-supercharged recipe for compost tea — to transform her own landscape from a roadside dump for broken asphalt to a garden that stops traffic, starting from the ground up.