By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

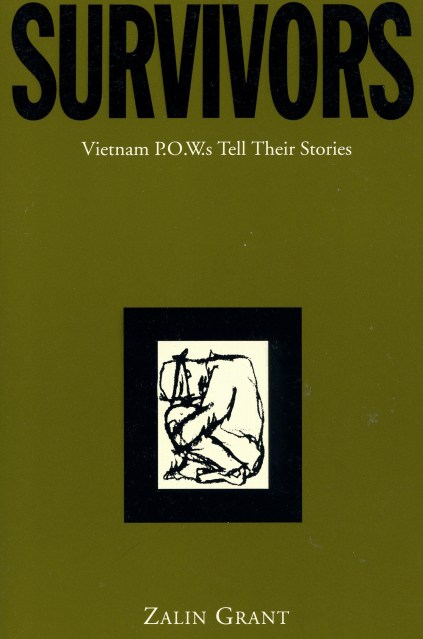

Survivors

Vietnam P.o.w.s Tell Their Stories

Contributors

By Zalin Grant

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 22, 1994

- Page Count

- 360 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306805615

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 22, 1994. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Nine Americans who fought in Vietnam, were taken prisoner, and somehow survived five agonizing years of captivity tell us exactly what they did, saw, and suffered. Here is the uncensored reality of the war.”–Gilbert A. Harrison, former editor-in-chief, New Republic

This book is the moving story of nine American soldiers and pilots who were captured and held prisoner for five years. It could only be told in their own words; so author Zalin Grant interviewed each of the men and wove their accounts together to form a single, compelling narrative of war and survival. They describe the details of their daily existence in a Vietcong jungle prison as the war ebbed and flowed around them: the rats, the terror of American bombing raids, the sickness, starvation, and torture. Through the juxtaposition of their individual stories we see the subtle, destructive tensions that operate on a group of men in such desperate circumstances.

Marched up the Ho Chi Minh trail to Hanoi, the prisoners’ physical ordeal gave way to an agonizing moral dilemma. Should they join the “Peace Committee,” a group of POWs protesting the war? Or should they resist their captors by all possible means as ordered by the secret American commander of the Hanoi prison? After years in the jungle on the edge of survival, each man had to answer the questions: Who am I? What do I believe? These men form a cross section of the army we sent to Vietnam. Their words illuminate not only their individual background and experience, but also the meaning of this war for all of us.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use