By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

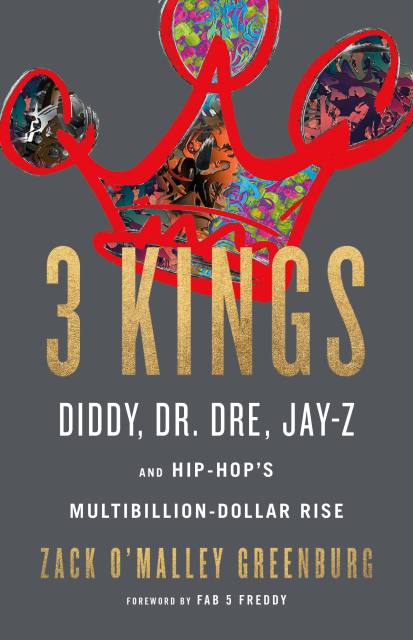

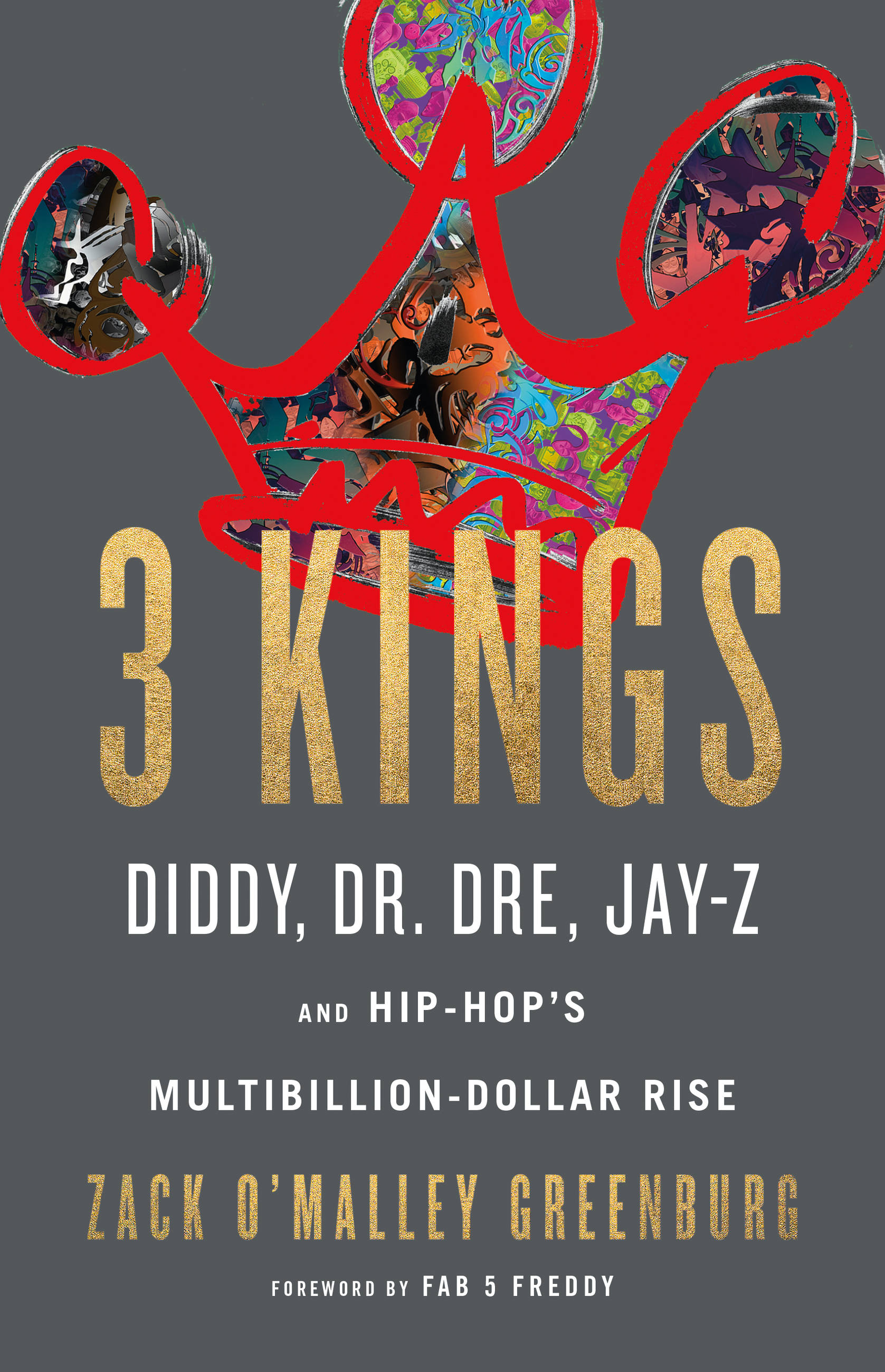

3 Kings

Diddy, Dr. Dre, Jay-Z, and Hip-Hop's Multibillion-Dollar Rise

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316316552

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Being successful musicians was simply never enough for the three kings of hip-hop. Diddy, Dr. Dre, and Jay-Z lifted themselves from childhood adversity into tycoon territory, amassing levels of fame and wealth that not only outshone all other contemporary hip-hop artists, but with a combined net worth of well over $2 billion made them the three richest American musicians, period.

Yet their fortunes have little to do with selling their own albums: between Diddy’s Ciroc vodka, Dre’s $3 billion sale of his Beats headphones to Apple, and Jay-Z’s Tidal streaming service and other assets, these artists have transcended pop music fame to become lifestyle icons and moguls.

Hip-hop is no longer just a musical genre; it’s become a way of life that encompasses fashion, film, food, drink, sports, electronics and more — one that has opened new paths to profit and to critical and commercial acclaim. Thanks in large part to the Three Kings — who all started their own record labels and released classic albums before moving on to become multifaceted businessmen — hip-hop has been transformed from a genre spawned in poverty into a truly global multibillion-dollar industry.

These men are the modern embodiment of the American Dream, but their stories as great thinkers and entrepreneurs have yet to be told in full. Based on a decade of reporting, and interviews with more than 100 sources including hip-hop pioneers Russell Simmons and Fab 5 Freddy; new-breed executives like former Def Jam chief Kevin Liles and venture capitalist Troy Carter; and stars from Swizz Beatz to Shaquille O’Neal, 3 Kings tells the fascinating story of the rise and rise of the three most influential musicians in America.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use