By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

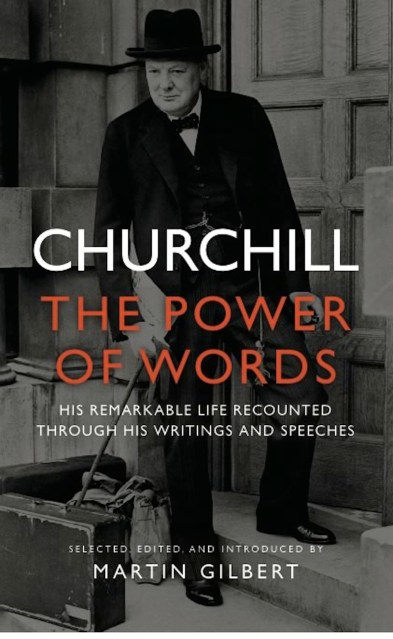

Churchill

The Power of Words

Contributors

Edited by Martin Gilbert

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $19.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 5, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Winston Churchill knew the power of words. In speeches, books, and articles, he expressed his feelings and laid out his vision for the future. His wartime writings and speeches have fascinated generation after generation with their powerful narrative style and thoughtful reflection.

Martin Gilbert, Churchill’s official biographer, has chosen passages that express the essence of Churchill’s thoughts and describe-in his own inimitable words-the main adventures of his life and the main crises of his career. From first to last, they give insight into his life, how it evolved, and how he made his mark on the British and world stage.

-

"Will give the reader great insight into the history of Britain during the time of Churchill and Churchill's own development into the leader during their 'finest hour.' Highly recommended especially in this age of politics over character."Sacramento Book Review

-

"With 200 extracts well chosen by historian and Churchill biographer Martin Gilbert, this book isn't just informative and entertaining. It's inspiring."Charleston Post and Courier

-

"What makes this particular volume stand out is the expert's encyclopedic knowledge about the subject--and his keen eye in choosing the most exceptional works of a man who wrote and spoke so many of them. Mr Gilbert has long been Churchill's greatest champion, but he wisely takes a secondary role to simply provide brief thoughts on each excerpt's historical significance. In doing so, Churchill's astonishing mastery of the English language can thereby do all the talking...a superb volume of Churchill's writings and speeches."Washington Times

-

"A masterful book and a history worth buying and reading and paying attention to."Veterans Reporter

-

"Winston Churchill's speeches...sing in a way English language statesmen and politicians have tried unsuccessfully to match ever since. This volume has them all, and in chronological order, often with brief lead-ins to supply context, so it can be read as a history of the British Empire during the first half of the 20th century, or used as an anthology of Churchillian quotations...Kudos to Sir Gilbert for the service he has performed in packing the best of Churchill into one comprehensible volume."Buffalo News

- On Sale

- Jun 5, 2012

- Page Count

- 536 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306821615

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use