By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

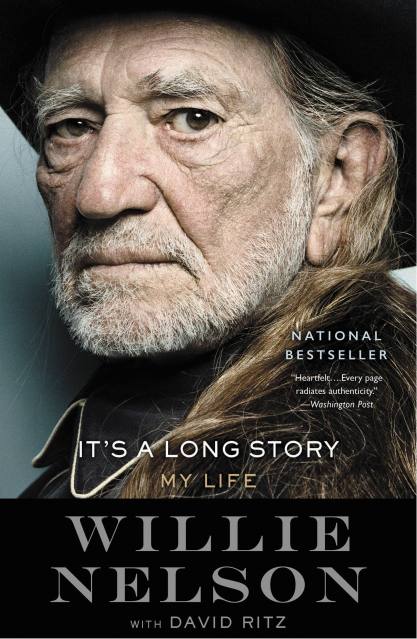

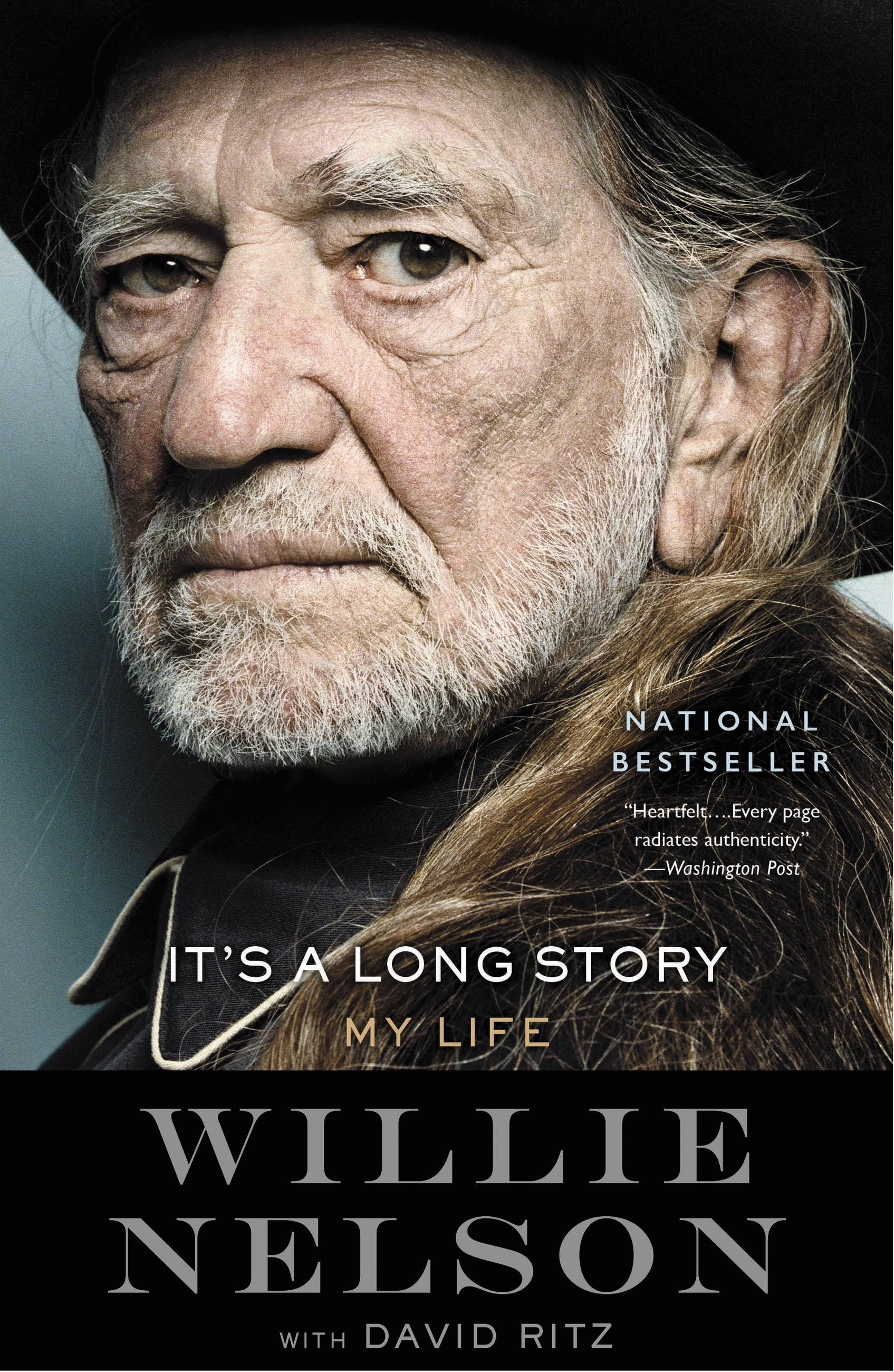

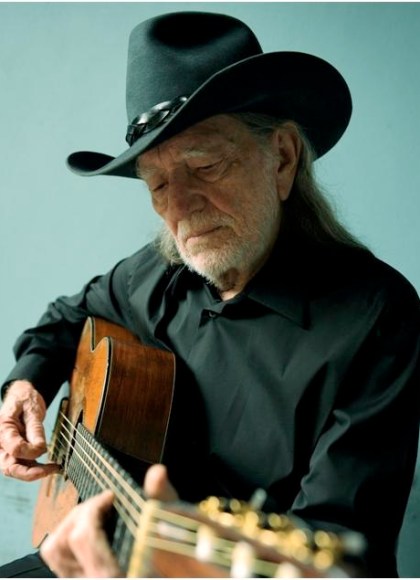

It’s a Long Story

My Life

Contributors

With David Ritz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 5, 2015

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316403566

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 5, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Unvarnished. Funny. Leaving no stone unturned.” . . . So say the publishers about this book I’ve written. What I say is that this is the story of my life, told as clear as a Texas sky and in the same rhythm that I lived it.

It’s a story of restlessness and the purity of the moment and living right. Of my childhood in Abbott, Texas, to the Pacific Northwest, from Nashville to Hawaii and all the way back again. Of selling vacuum cleaners and encyclopedias while hosting radio shows and writing song after song, hoping to strike gold.

It’s a story of true love, wild times, best friends, and barrooms, with a musical sound track ripping right through it. My life gets lived on the road, at home, and on the road again, tried and true, and I’ve written it all down from my heart to yours.

Signed, Willie Nelson.

-

"A smooth-spoken recollection of the country legend's childhood and his eight-decade-long musical career.... Just like this book -- and its subject -- direct and genuine."Mike Snider, USA Today

-

"Invaluable... Nelson writes the way he sings and plays guitar--with conversational ease and grace."James Reed, The Boston Globe

-

"Every page radiates authenticity.... Heartfelt...."Douglas Brinkley, The Washington Post

-

"Endlessly entertaining.... Readers of It's a Long Story will finally get the sense that Nelson is sitting before them spilling everything he can remember.... It's a wonderful thing if you love ol' Willie -- and who doesn't? ... Nelson has spent decades on the road building this story -- do yourself a favor and take a day or two to read it."Hunter Hauk, Dallas Morning News

-

"Brims with affectionate reminiscences of Nelson's childhood and semi-wayward youth, his turbulent marriages and career zigzags. And of course his raison d'être, music."Leah Greenblatt, Entertainment Weekly

-

A "breezy new autobiography... His voice as a writer, as in song, is warm, generous and good-timey."James Sullivan, San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Nelson offers a warm, friendly, and a deeply reflective glimpse behind the making of most of his albums as well as behind-the-scenes looks at some of his best-known hits.... Reading Nelson's narrative is like sitting on the front porch chatting with an old friend."Publishers Weekly

-

A "candid, heartfelt memoir.... In a plainspoken, conversational tone reminiscent of his singing voice."Dave Shiflett, Wall Street Journal

-

"The closing chapters are reflective and heartfelt--part musical and part personal--and they nicely bookend Nelson's admirable attempt to recount his 'long story.'"Andrew Dansby, The Houston Chronicle

-

"One of the original 'outlaw' country singers puts it all on the line with this bawdy and moving tale of his extraordinary life."Allen Pierleoni, The Sacramento Bee

-

"As breezy, entertaining and occasionally bizarre as the man himself."Larry Getlen, New York Post

-

"An autobiography that ought to be on any Southern music lover's shelf--this is Willie in his own authentic voice, sharing memories of his Texas upbringing."CJ Lotz, Garden & Gun

-

It's a Long Story "is closer to a series of Raymond Carver stories: terse, conversational and peppered with profanity, jokes and life lessons.... One of the great stories in American music."Jim Kiest, San Antonio Express-News

-

"This is the definitive Willie Nelson story. It's a rare insight into an American folk hero, one told in a voice as powerful and genuine as the red-headed stranger himself."Mark Flanagan, Run Spot Run

-

"The often hilarious and sometimes heartbreaking story of a life on the run."Woody Harrelson, Interview

-

"This rollicking bio perfectly captures the inimitable voice of his plain-speaking subject."Sarah Murdoch, Toronto Star

-

"Who doesn't love trigger-wielding Willie Nelson? ... Pour a drink, take a seat and dig into the life story of one of America's true living legends."Parade

-

"One of America's most gifted songwriters and storytellers, Nelson mesmerizes us with his gift of gab in this autobiography, regaling us with stories of his life -- from his childhood and youth in Abbott, TX, to the ups and downs of his marriages, and his deep love for his family, friends, fans, and songwriting."Henry Carrigan, No Depression

-

"Country music legend Willie Nelson tells his life story his way, with humor and outright honesty. Most of the time, it feels as if he is sitting right across the table talking directly to us, pouring out his heart and soul."Christine M. Irvin, BookReporter

-

"Nelson recounts a colorful life story in and out of music. And what a life it has been."Bob Ruggiero, Houston Press

-

"Warm, witty, and burnished with cowboy mystic wisdom."Tim Stegall, The Austin Chronicle

-

"Long Story thrives on the basis of two factors: Nelson's short sentences, chalk-full of his deadpan wit and the larger-than-life tales he shares.... Nelson's sage and easy-going spin on these various yarns, and the morals he offers up in his summations, are endearing and entertaining.... Essential reading."James Courtney, San Antonio Current

-

"A fascinating memoir of a living American icon. It is as colorful as Willie's life has been. Written in a very beautiful and gripping style, Nelson's book reads like a novel."The Washington BookReview

-

"It's a Long Story proves to capture the Red Headed Stranger in a direct light, and fans have plenty to gain within its pages."Tyler R. Kane, Paste Magazine's "The 15 Best Nonfiction Books of 2015 (So Far)"

-

"As a kid, Willie Nelson wrote poetry. From an early age, he understood the power of a simple, direct voice and it's this voice that makes My Life more than just another run-of-the-mill, music industry memoir.... You don't need to be a fan to be beguiled by his gift for spinning a yarn."Fiona Capp, The Sydney Morning Herald

-

Praise for Willie NelsonRolling Stone

"In a time when America is more divided than ever, Nelson could be the one thing that everybody agrees on." -

"One of those rare American icons that you're just not allowed to dislike....Loving Willie Nelson, like paying taxes and pretending to have an opinion about politics, is just part of being a citizen of the United States....A legend."Vanity Fair

-

"If America only had one voice it would be Willie's."Emmylou Harris

-

"Willie Nelson's impact on American music is indelible. He stands at the crossroads of all the sounds and colors of his country. What he reflects is true soul and sincerity."Carlos Santana

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use