Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

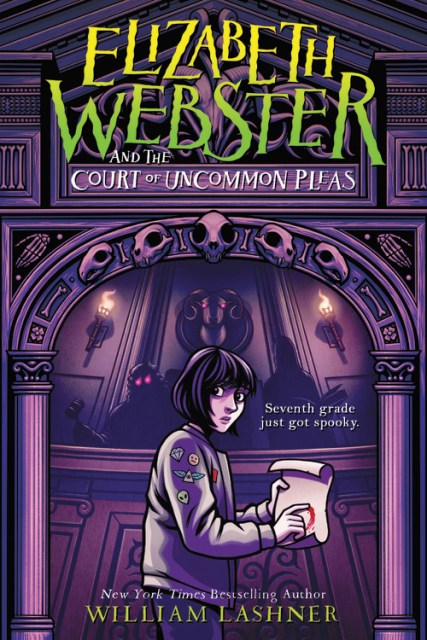

Elizabeth Webster and the Court of Uncommon Pleas

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 15, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Welcome to Elizabeth Webster’s world, where the common laws of middle school torment her days . . . and the uncommon laws of an even weirder realm govern her nights.

Elizabeth Webster is happy to stay under the radar (and under her bangs) until middle school is dead and gone. But when star swimmer Henry Harrison asks Elizabeth to tutor him in math, it’s not linear equations Henry really needs help with-it’s a flower-scented, poodle-skirt-wearing, head-tossing ghost who’s calling out Elizabeth’s name.

But why Elizabeth? Could it have something to do with her missing lawyer father? Maybe. Probably. If only she could find him. In her search, Elizabeth discovers more than she is looking for: a grandfather she never knew, a startling legacy, and the secret family law firm, Webster & Son, Attorneys for the Damned.

Elizabeth and her friends soon land in court, where demons and ghosts take the witness stand and a red-eyed judge with a ratty white wig hands out sentences like sandwiches. Will Elizabeth’s father arrive in time to save Henry Harrison-and is Henry the one who really needs saving?

Set in the historic streets of Philadelphia, this riveting middle-grade mystery from New York Times bestselling author William Lashner will have readers banging their gavels and calling for more from the incomparable Elizabeth Webster.

Elizabeth Webster is happy to stay under the radar (and under her bangs) until middle school is dead and gone. But when star swimmer Henry Harrison asks Elizabeth to tutor him in math, it’s not linear equations Henry really needs help with-it’s a flower-scented, poodle-skirt-wearing, head-tossing ghost who’s calling out Elizabeth’s name.

But why Elizabeth? Could it have something to do with her missing lawyer father? Maybe. Probably. If only she could find him. In her search, Elizabeth discovers more than she is looking for: a grandfather she never knew, a startling legacy, and the secret family law firm, Webster & Son, Attorneys for the Damned.

Elizabeth and her friends soon land in court, where demons and ghosts take the witness stand and a red-eyed judge with a ratty white wig hands out sentences like sandwiches. Will Elizabeth’s father arrive in time to save Henry Harrison-and is Henry the one who really needs saving?

Set in the historic streets of Philadelphia, this riveting middle-grade mystery from New York Times bestselling author William Lashner will have readers banging their gavels and calling for more from the incomparable Elizabeth Webster.

Genre:

-

I love this book! William Lashner delivers humor and ghost-story shivers in a mixture of wit and intensity. He creates memorable characters, at once daring and vulnerable.Ridley Pearson, bestselling author of Lock and Key

-

A superb mystery....Elizabeth's spunky attitude and earnestness provide an emotional spine that couples with the novel's mystery, dovetailing together at the right moment, making for a very engaging read.Kirkus Reviews

-

This blend of ghost story and mystery will satisfy readers who ask for the "scary stories."School Library Journal

- On Sale

- Sep 15, 2020

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781368065207

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use