Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

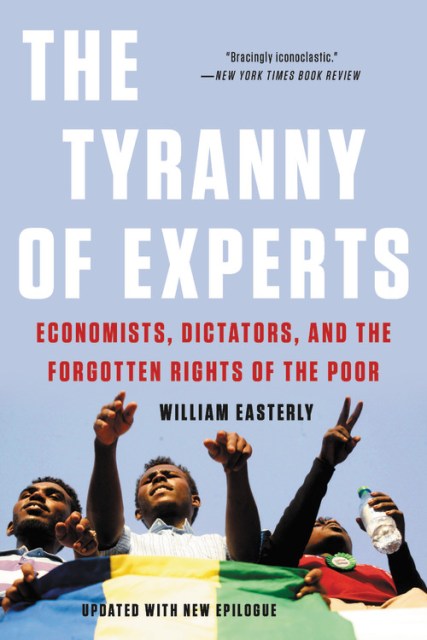

The Tyranny of Experts

Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In The Tyranny of Experts, renowned economist William Easterly examines our failing efforts to fight global poverty, and argues that the "expert approved" top-down approach to development has not only made little lasting progress, but has proven a convenient rationale for decades of human rights violations perpetrated by colonialists, postcolonial dictators, and US and UK foreign policymakers seeking autocratic allies. Demonstrating how our traditional antipoverty tactics have both trampled the freedom of the world's poor and suppressed a vital debate about alternative approaches to solving poverty, Easterly presents a devastating critique of the blighted record of authoritarian development. In this masterful work, Easterly reveals the fundamental errors inherent in our traditional approach and offers new principles for Western agencies and developing countries alike: principles that, because they are predicated on respect for the rights of poor people, have the power to end global poverty once and for all.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541675674

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use