By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

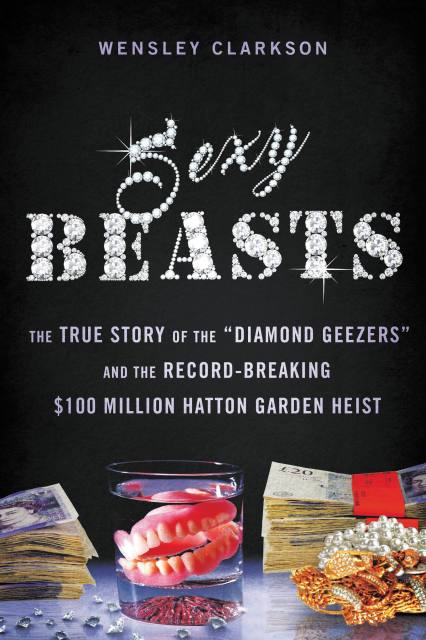

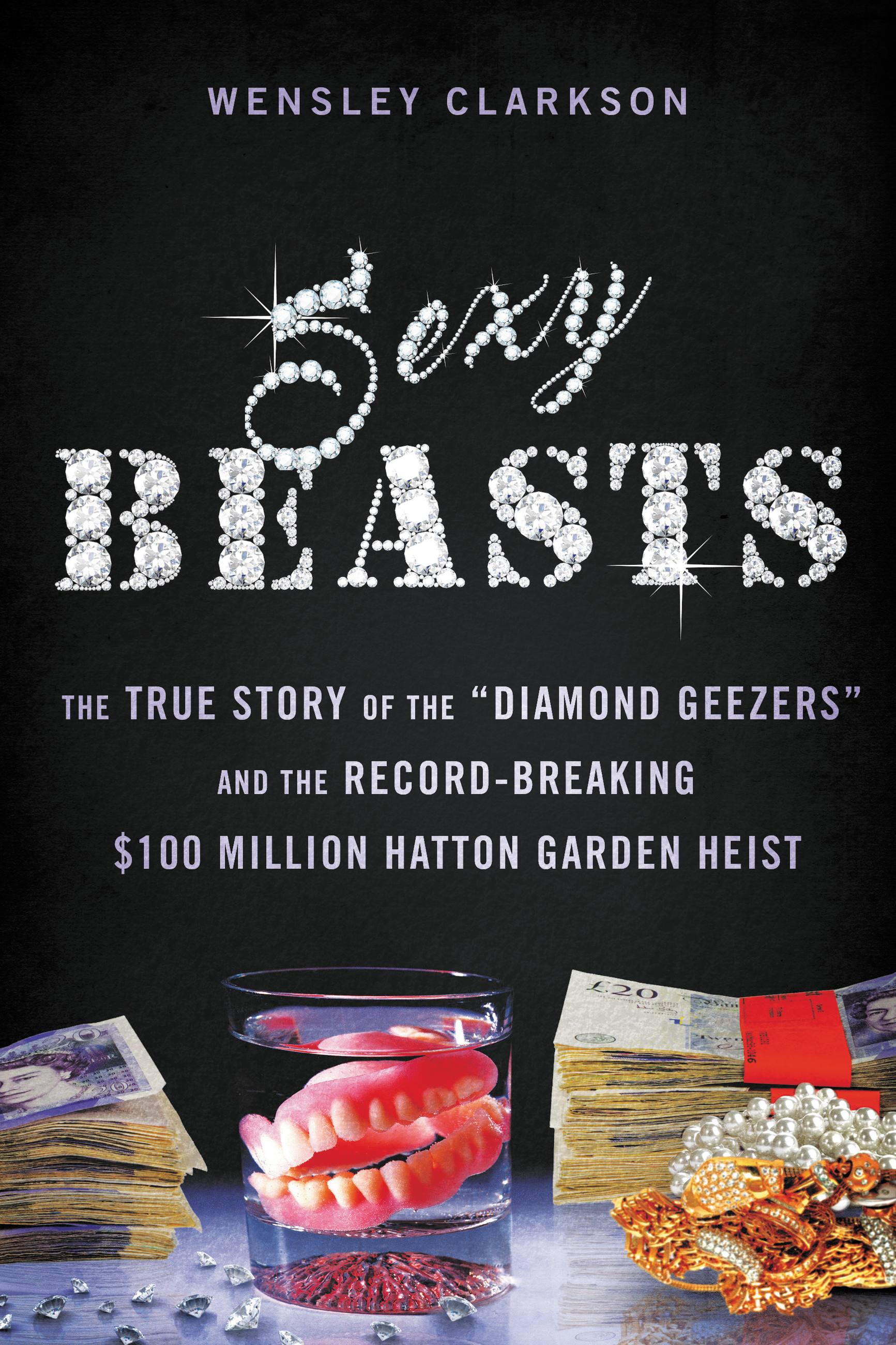

Sexy Beasts

The True Story of the "Diamond Geezers" and the Record-Breaking $100 Million Hatton Garden Heist

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2016

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316545945

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Hatton Garden Heist captured the British public’s imagination more than another other crime since The Great Train Robbery. It was supposed to make a fortune for a team of old time professional criminals. Their last hurrah. A final lucrative job that would send the old codgers off on happy retirements to the badlands of Spain and beyond. It seemed to be the stuff of legends. Tens of millions of dollars worth of valuables grabbed from safety deposit boxes in a vault beneath one of the most famous jewelry districts in the world.

But where did it all go wrong for this band of old time villains? And how did the gang’s bid to pull off the world’s biggest burglary turn into a deadly game of cat and mouse featuring the police and London’s most dangerous crime lords?

Nobody is better placed to reveal the full story of the Hatton Garden Heist than Britain’s best-connected true crime writer, Wensley Clarkson. Through his unparalleled contacts inside the criminal underworld, he’s finally able to reveal the astonishing details behind Britain’s biggest ever burglary.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use