Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

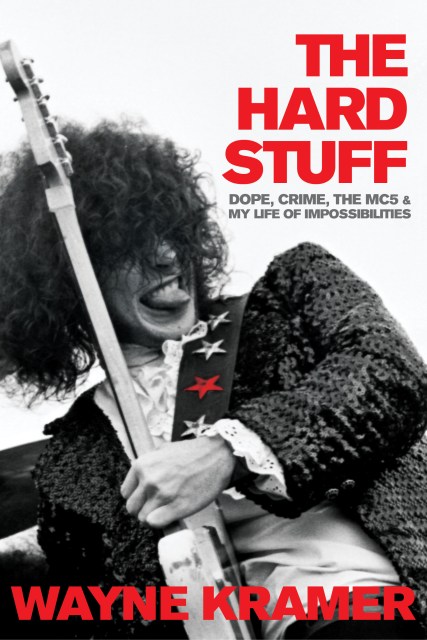

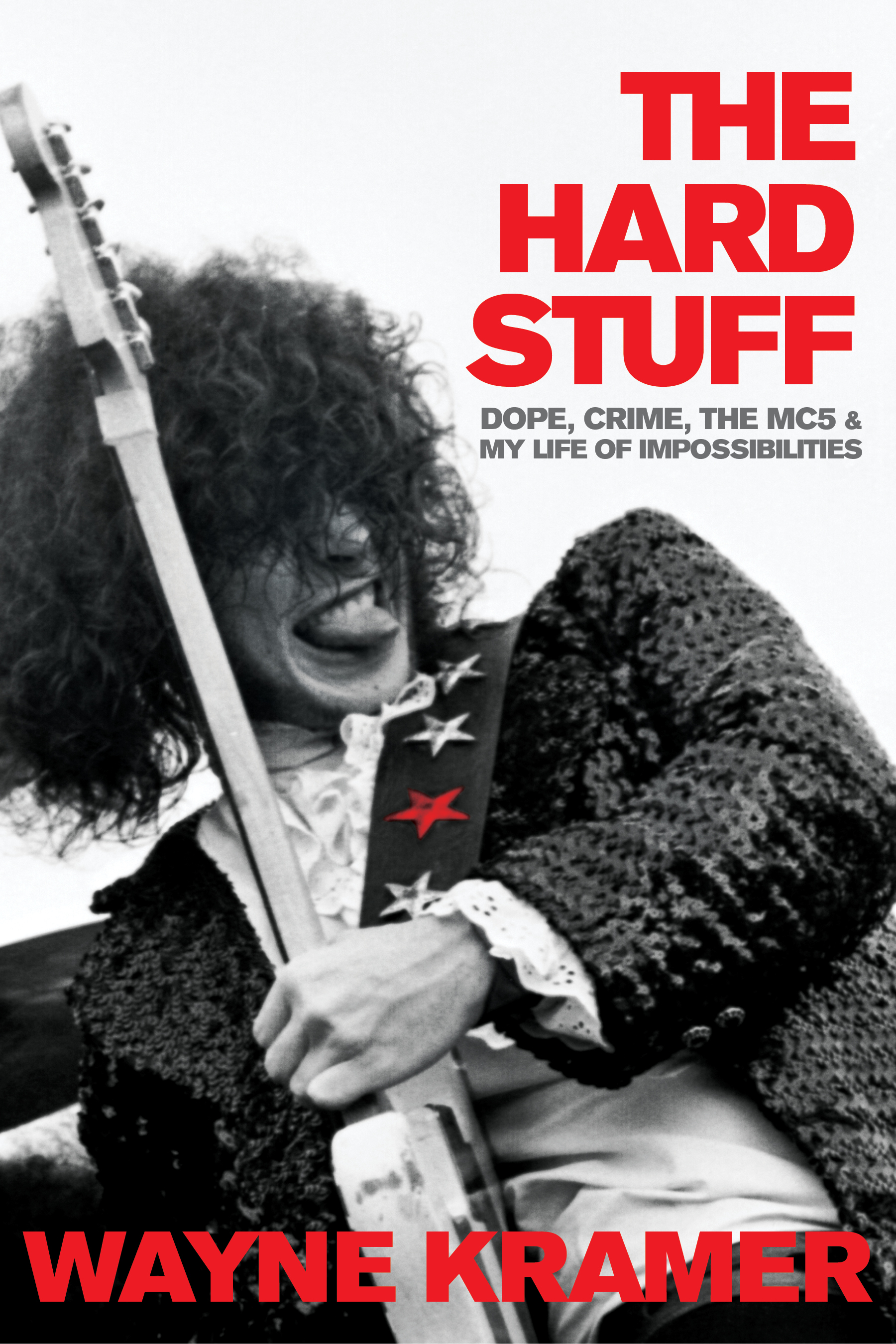

The Hard Stuff

Dope, Crime, the MC5, and My Life of Impossibilities

Contributors

By Wayne Kramer

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$4.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $4.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 14, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Voyeuristically dramatic.”–THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

In January 1969, before the world heard a note of their music, the MC5 was on the cover of Rolling Stone. Led by legendary guitarist Wayne Kramer, the band was a reflection of the times: exciting, sexy, violent, chaotic, and even out of control. The missing link between free jazz and punk rock, the MC5 toured the country, played alongside music legends, and had a rabid following, their music acting as the soundtrack to the blossoming blue collar youth movement. Kramer wanted to redefine what a rock ‘n’ roll group was capable of, and though there was power in reaching for that, it was also a recipe for personal and professional disaster. The band recorded three major label albums but, by 1972-it was all over. Kramer’s story is (literally) a revolutionary one, but it’s also the deeply personal struggle of an addict and an artist, a rebel with a great tale to tell. From the glory days of Detroit to the junk-sick streets of the East Village, from Key West to Nashville and sunny L.A., in and out of prison and on and off of drugs, Kramer’s is the classic journeyman narrative, but with a twist: he’s here to remind us that revolution is always an option.

In January 1969, before the world heard a note of their music, the MC5 was on the cover of Rolling Stone. Led by legendary guitarist Wayne Kramer, the band was a reflection of the times: exciting, sexy, violent, chaotic, and even out of control. The missing link between free jazz and punk rock, the MC5 toured the country, played alongside music legends, and had a rabid following, their music acting as the soundtrack to the blossoming blue collar youth movement. Kramer wanted to redefine what a rock ‘n’ roll group was capable of, and though there was power in reaching for that, it was also a recipe for personal and professional disaster. The band recorded three major label albums but, by 1972-it was all over. Kramer’s story is (literally) a revolutionary one, but it’s also the deeply personal struggle of an addict and an artist, a rebel with a great tale to tell. From the glory days of Detroit to the junk-sick streets of the East Village, from Key West to Nashville and sunny L.A., in and out of prison and on and off of drugs, Kramer’s is the classic journeyman narrative, but with a twist: he’s here to remind us that revolution is always an option.

Genre:

-

"Voyeuristically dramatic."New York Times Book Review

-

"[This] book comes alive when bringing the reader into the heart of the late-'60s scene, where revolution seemed not just possible but plausible...The Hard Stuff is rarely poetic, but in its brutal honesty Mr. Kramer may succeed in deterring future musicians from contemplating serious drug abuse."Wall Street Journal

-

"Kramer has written one of rock's most engaging and readable memoirs."Rolling Stone

-

"By the time he turned 30, Kramer had been the lead guitarist in a legendary but star-crossed rock band, a playacting Detroit gangster, and a guest of the American carceral system. All this living is covered in his new memoir The Hard Stuff, along with Kramer's roundabout path to the life he leads today."NPR Music

-

"There's nothing like an autobiography when it comes to really digging deep. Kramer's The Hard Stuff does exactly that. It's simultaneously brutally honest, heartbreaking, hilarious, and life-affirming...It's a frankly wonderful read."Detroit Metro Times

-

"Often harrowing, sometimes hilarious and always compelling."Buffalo News

-

"The 1960s rocker and (sometimes) revolutionary pulls no punches in his autobiography, delivering a detailed look at his life good (leading the rock powerhouse MC5, political activism during the late 1960s and early '70s) and bad (drugs, prison) in a voice as clear as the vocals on MC5's 'Kick Out the Jams.'"Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

-

"An honest accounting of everything the title states, from the rapid rise and fall of the MC5 over the course of three albums, the heroin addiction and drug dealing that landed him in prison, and ultimately the defeat of those demons, redemption, and late-in-life fatherhood that he calls 'the most meaningful thing I've ever done.'"Orange County Register

-

"The book, while detailing the struggle of an addict and an artist, is layered with the optimism of a man committed to seeing past impossibilities."South Florida Sun-Sentinel

-

"For all the hardness of his life, his insights into addiction-drawn from his own, and his absent father's alcoholism-are shot through with an enduring, thoughtful empathy that makes The Hard Stuff such an endearing read."MOJO

-

"Kramer writes with a self-lacerating clarity about life in The MC5 and their chaotic slide into drugs, disorder and prison. Every grim inch of the trip from boundary-smashing idealism to dingy realty is here, with a twist of redemption at the end."Q Magazine

-

"Relives those energising days of the late '60s, when Detroit's MC5 mixed rock and revolution with free jazz and exceptional hair...An inspiring and redemptive tale."Uncut

-

"A book as suited to the sociology section as the music aisle."The Guardian

-

"He defied death, drugs and detention. Now MC5 legend Wayne Kramer has written an equally full-on memoir...Eye-opening...Wide-ranging...His journey from fatherless child to musical maverick to junkie to upstanding survivor reads like a history of the late 20th century."TheObserver

-

"The MC5 are the ultimate cult band: a rebellious group from late-1960s Detroit whose raw, proto-punk take on rock'n'roll influenced everyone from the Sex Pistols to Primal Scream. They never made it, though, and when you read this memoir by the guitarist and leader Wayne Kramer, you begin to see why. The Hard Stuff can be read as a manual of how not to become a rock star. Drugs, band feuds, jail and radical politics all combined to prevent stardom. This is a story of bad luck and bad behaviour in equal measure."Times of London

-

"By blending his own narrative with the trials of MC5 and by merging musical rebellion with social justice, the author has penned a contemplative diatribe against political authority."Library Journal

-

"A thorough examination of his life, including musical adventures and drug misadventures that ultimately landed him in jail... The Hard Stuff covers the entirely of Kramer's life, with no attempts to hide any warts."Billboard.com

-

"The Hard Stuff is a raw account of Kramer's life growing up in the increasingly mean streets of post-World War II Detroit, the glorious rise and precipitous fall of the MC5, and his decades-long addiction to drugs that led to his two-year bid in a federal penitentiary."VICE's Noisey

-

"There's no hyperbole in saying that The MC5 were one of the most important bands to emerge from America during the 1960s, which is why it's so great that Wayne Kramer, one of the founding members of the band, decided to sit down and write himself a memoir...The end result-The Hard Stuff-turned out spectacularly."Rhino

-

"Kramer's life has been a raging roller-coaster of euphoric highs and bottom-feeder lows. The now-sober superstar talks about all of it-the student demonstrations, police riots, crazy concerts, drug-fueled debauchery, wiretapping, marriages and divorce, prison time, therapy, recovery, and redemption-in his new memoir...Sure, we've been awed by other rock autobiographies...but we've never encountered a tale as turbulent and gritty as Kramer's. The Hard Stuff is a brisk, brutal page-turner wherein the Motor City 'white boy with the wah-wah' candidly chronicles the formation of one of rock's most outrageous ensembles."AXS.com

-

"Wayne Kramer's story is an incredible tale of rock 'n' roll redemption. The MC5 crystallized the '60s counterculture movement at its most volatile and basically invented punk rock music. But Wayne's life proved to be as chaotic as his groundbreaking guitar playing. Rogue, rascal, rebel, revolutionary, artist, addict, inmate, poet, prisoner, and now proud papa, Brother Wayne Kramer is one of the wisest people I know, and he has earned that wisdom the hard way. The world needs to know this man's story. Here it is."TomMorello, guitarist of Rage Against the Machine, Audioslave, and Prophets ofRage

-

"Wayne Kramer is the biggest badass in rock 'n' roll. Period. And The Hard Stuff proves it. Between these covers is a story of survival, talent, madness, dope, guts, and a sheer, fearless commitment to bringing straight-up enlightenment to this fascist, prison-happy nation we happen to inhabit--even if it meant putting his own freedom, and his own unbelievably epic life, on the line. This just may be the best memoir of the year."Jerry Stahl, author of I, Fatty and Permanent Midnight

-

"Wayne Kramer bore first-hand witness to an unparalleled era of rebellion, freedom, and total craziness. The Hard Stuff brings that milieu back-to-life with a wildly compelling, vivid, and eloquent portrayal. It's the next best thing to having actually been there. I binge-read the whole book and, for the next week, could smell and taste the Grande Ballroom in my mind."Don Was, producer andfounder of Was (Not Was)

-

"Reading Wayne Kramer's painfully honest autobiography was like savoring a real-life reverse murder mystery: how he ever survive to write this? World-class rock and jazz musician at the age of 20, progenitor of punk with the MC5, political and cultural revolutionary, heroin addict, alcoholic, residential B&E burglar, drug dealer, federal convict, nothing's omitted. Future generations of disaffected kids will read The Hard Stuff to learn the miracle of a life of music and survival."Mark Rudd, author of Underground: My Life with SDS and theWeathermen

-

"In the grand literary tradition of finding meaning in the course of a life, guitar legend and rock music icon Wayne Kramer's deep and insightful memoir The Hard Stuff stands out like one of his piercing Fender solos. This is the story of a man ahead of his time, who has managed to carve a real life out of the shards of the magical but self-destructive life of his youth. Real wisdom arises from pain and loss, and Kramer has the chops to claim his place as a modern-day sage. That he stays grateful and humble is the best evidence of his personal growth. Read this memoir for a glimpse into the deepest reality of the human experience."Kenneth E. Hartman,former prisoner, justice reform activist, and author of the Eric HofferAward-winning memoir Mother California: A Story of Redemption BehindBars

- On Sale

- Aug 14, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306921537

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use