Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

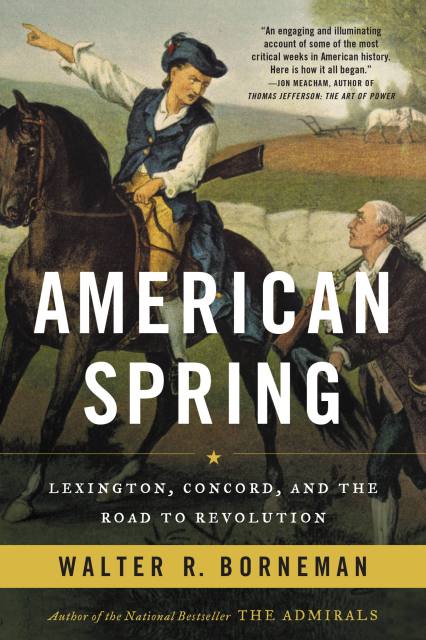

American Spring

Lexington, Concord, and the Road to Revolution

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.00 $20.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 6, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A vibrant look at the American Revolution’s first months, from the author of the bestseller The Admirals.

When we reflect on our nation’s history, the American Revolution can feel almost like a foregone conclusion. In reality, the first weeks and months of 1775 were very tenuous, and a fractured and ragtag group of colonial militias had to coalesce rapidly to have even the slimmest chance of toppling the mighty British Army.

American Spring follows a fledgling nation from Paul Revere’s little-known ride of December 1774 and the first shots fired on Lexington Green through the catastrophic Battle of Bunker Hill, culminating with a Virginian named George Washington taking command of colonial forces on July 3, 1775.

Focusing on the colorful heroes John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, Benjamin Franklin, and Patrick Henry, and the ordinary Americans caught up in the revolution, Walter R. Borneman uses newly available sources and research to tell the story of how a decade of discontent erupted into an armed rebellion that forged our nation.

When we reflect on our nation’s history, the American Revolution can feel almost like a foregone conclusion. In reality, the first weeks and months of 1775 were very tenuous, and a fractured and ragtag group of colonial militias had to coalesce rapidly to have even the slimmest chance of toppling the mighty British Army.

American Spring follows a fledgling nation from Paul Revere’s little-known ride of December 1774 and the first shots fired on Lexington Green through the catastrophic Battle of Bunker Hill, culminating with a Virginian named George Washington taking command of colonial forces on July 3, 1775.

Focusing on the colorful heroes John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, Benjamin Franklin, and Patrick Henry, and the ordinary Americans caught up in the revolution, Walter R. Borneman uses newly available sources and research to tell the story of how a decade of discontent erupted into an armed rebellion that forged our nation.

Genre:

-

Praise for American Spring:David Shribman, Boston Globe

"Likely to be one of the enduring accounts of the opening of the American Revolution.... Loaded with intriguing details, sort of historical nonpareil candies sprinkled throughout the account.... A pleasing marriage of scholarly research and approachable language." -

"Walter Borneman has written an engaging and illuminating account of some of the most critical weeks in American history. Here is how it all began." -- Jon Meacham, author of Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power

-

"Borneman delivers a gripping, almost moment-by-moment account of the nasty exchanges and bloody retreat of British troops followed by hundreds and then thousands of militia who camped around Boston and laid siege.... A first-rate contribution."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

Praise for The Admirals:

"Superbly reported... Historian Walter R. Borneman tackles the essential question of military leadership: What makes some men, but not others, able to motivate a fighting force into battle?" -- Tony Perry, Los Angeles Times -

"Engagingly written and deeply researched... Mr. Borneman makes it easy to understand the complex series of maneuvers and counter-maneuvers at Leyte Gulf...which is not always the case with accounts of the battle." -- Andrew Roberts, Wall Street Journal

-

"The first book to deal with the four [admirals] together, focusing on their intertwined lives, friendships, and rivalries.... Very well-crafted." -- John Lehman, Washington Post

-

"A riveting introduction to the only four men in American history to have been promoted to the five-star rank of Admiral of the Fleet in recognition of their extraordinary feats." -- The History Channel

-

"An epic group portrait of Nimitz, Halsey, Leahey, and King. Not since the heyday of Samuel Eliot Morison has a historian painted such a fine portrait of the five-star admirals who helped America beat Japan during the Second World War. Highly recommended!" -- Douglas Brinkley, Professor of History at Rice University and author of The Wilderness Warrior

-

"They were completely different in temperament and personality, but the U.S. Navy's four five-star admirals in World War II shared a sense of vision, devotion, and courage. Walter Borneman has written a rousing tale of victory at sea." -- Evan Thomas, author of The War Lovers

-

"This is Walter Borneman at his best. The portrait of the forgotten admiral, Leahy, is worth the whole book. But there's scarcely a page where a reader won't learn something unexpected, and occasionally shocking." -- Thomas Fleming, author of Time and Tide

- On Sale

- May 6, 2014

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316221016

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use