By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Blue Mind

The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In, On, or Under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected, and Better at What You Do

Contributors

Foreword by Céline Cousteau

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 22, 2014

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316252072

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- ebook (Revised) $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 22, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

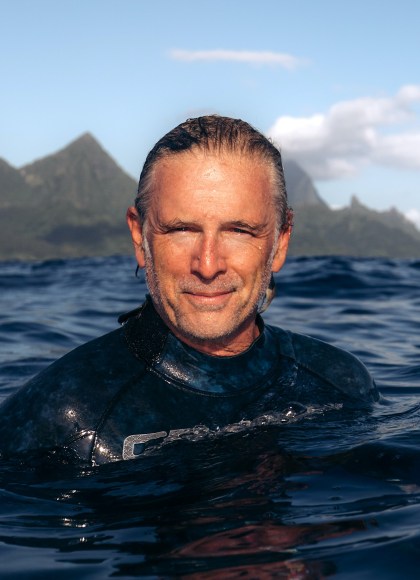

Why are we drawn to the ocean each summer? Why does being near water set our minds and bodies at ease? In Blue Mind, Wallace J. Nichols revolutionizes how we think about these questions, revealing the remarkable truth about the benefits of being in, on, under, or simply near water.

Combining cutting-edge neuroscience with compelling personal stories from top athletes, leading scientists, military veterans, and gifted artists, he shows how proximity to water can improve performance, increase calm, diminish anxiety, and increase professional success. Blue Mind not only illustrates the crucial importance of our connection to water; it provides a paradigm shifting “blueprint” for a better life on this Blue Marble we call home.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use