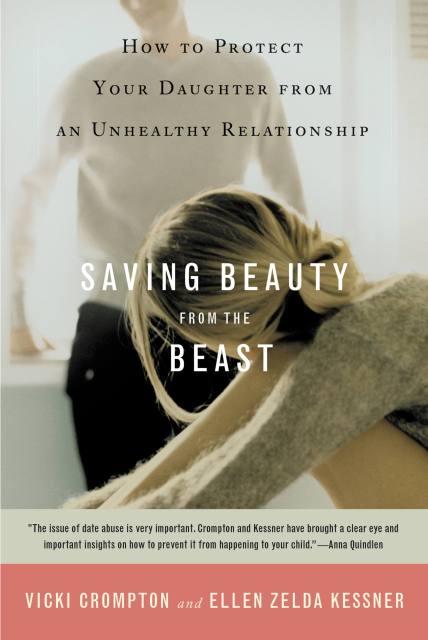

Saving Beauty from the Beast

How to Protect Your Daughter from an Unhealthy Relationship

Contributors

By Vicki Crompton

By Ellen Zelda Kessner

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 3, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This essential and timely book incorporates the insights and advice of experts in the fields of education, adolescent psychology, criminal justice, threat assessment, and sociology. Authors Crompton and Kessner also include the voices of teenagers and parents to provide an in-depth portrait of the dynamics of controlling behavior.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 3, 2007

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316030045

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use