Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

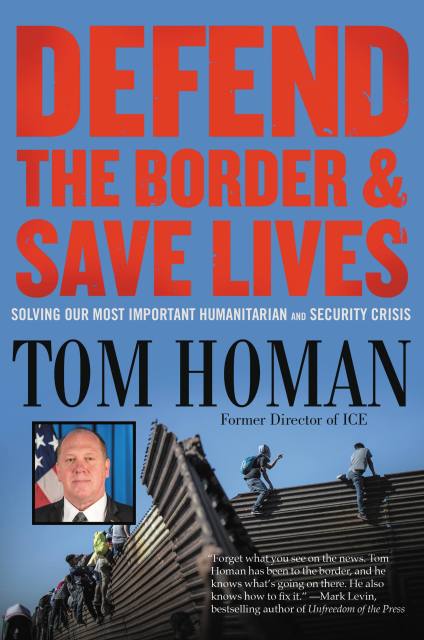

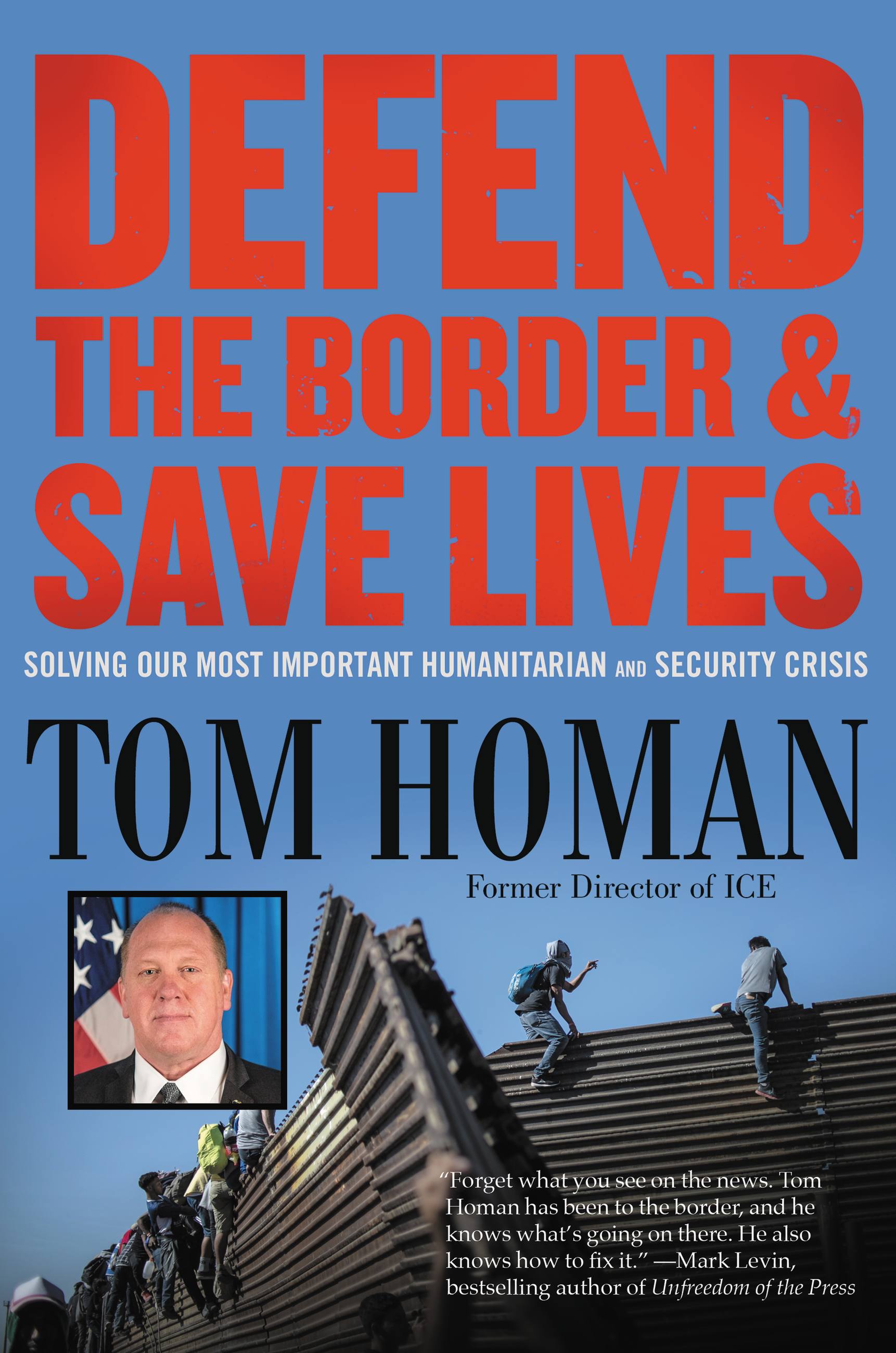

Defend the Border and Save Lives

Solving Our Most Important Humanitarian and Security Crisis

Contributors

By Tom Homan

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 31, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Illegal immigration is the most controversial and emotional issue this country faces today. President Trump was elected on his promise to fix illegal immigration and build a wall on our southern border. Because he won on this issue, the Democrats refuse to work with him, and we experienced a government shutdown as a result of this divide. The Democrats have supported funding in the past and, in his State of the Union, the President said that he wants to unify and work together to resolve this and all the other challenges facing America. The Democrats sat on their hands. They won't budge. Clearly, as a party, they don't care about the facts, only about denying whatever success they can to this president.

Former ICE Director and Fox News contributor Tom Homan knows the facts. He's spent his life on the border and knows that if we don't control illegal immigration now, this country will continue to suffer the consequences of crime, drugs, and financial strain—and it will get much much worse.

In Defend the Border and Save Lives, Homan shares what illegal immigration is really about. Illegal immigration should not be a partisan issue. Now is the time to fix this issue that has claimed so many victims and divided this country. We need to pull the curtain back and expose what truly happens and separate facts from fiction. Illegal immigration is not a victimless crime, and the victims are the illegals and their innocent children as well as the Americans who suffer at the hand of the criminals who sneak into this country.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 31, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546085942

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use