Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

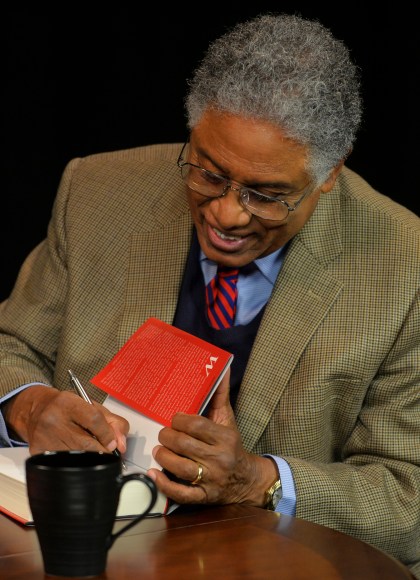

Wealth, Poverty and Politics

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$25.99Price

$33.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $25.99 $33.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 6, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Sowell contends that liberals have a particular interest in misreading the data and chastises them for using income inequality as an argument for the welfare state. Refuting Thomas Piketty, Paul Krugman, and others on the left, Sowell draws on accurate empirical data to show that the inequality is not nearly as extreme or sensational as we have been led to believe.

Transcending partisanship through a careful examination of data, Wealth, Poverty, and Politics reveals the truth about the most explosive political issue of our time.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 6, 2016

- Page Count

- 576 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096770

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use