Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

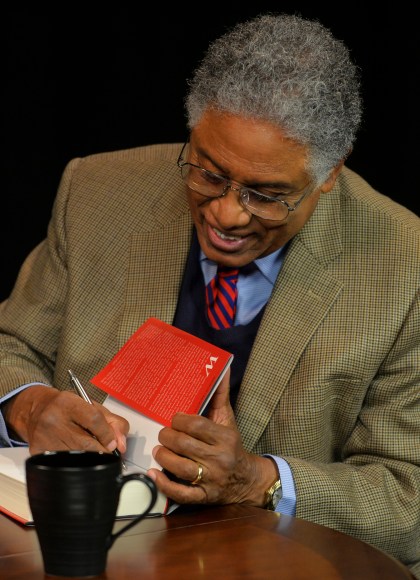

The Housing Boom and Bust

Revised Edition

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (Revised) $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 23, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The politics behind all this is another story full of strange twists. No punches are pulled when discussing politicians of either party, the financial dangers they created, or the distractions they created later to escape their own responsibility for what happened when the financial house of cards in the financial markets collapsed.

What to do, now that we are in the midst of an economic disaster, is yet another story — one whose ending we do not yet know, but one whose outlines and implications are explored to reveal some surprising and sobering lessons.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 23, 2010

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786747559

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use