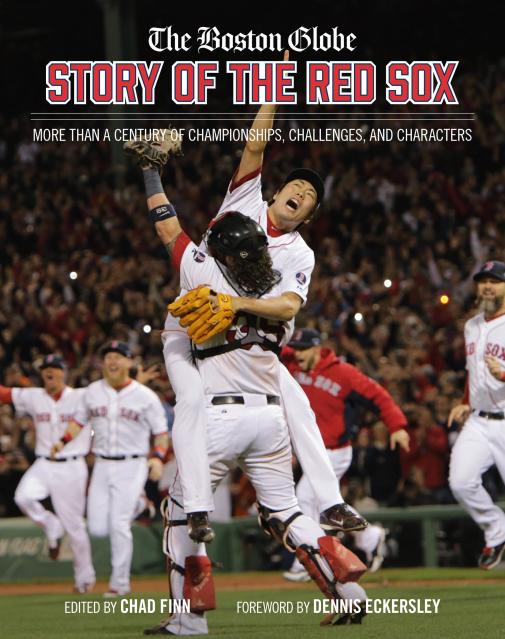

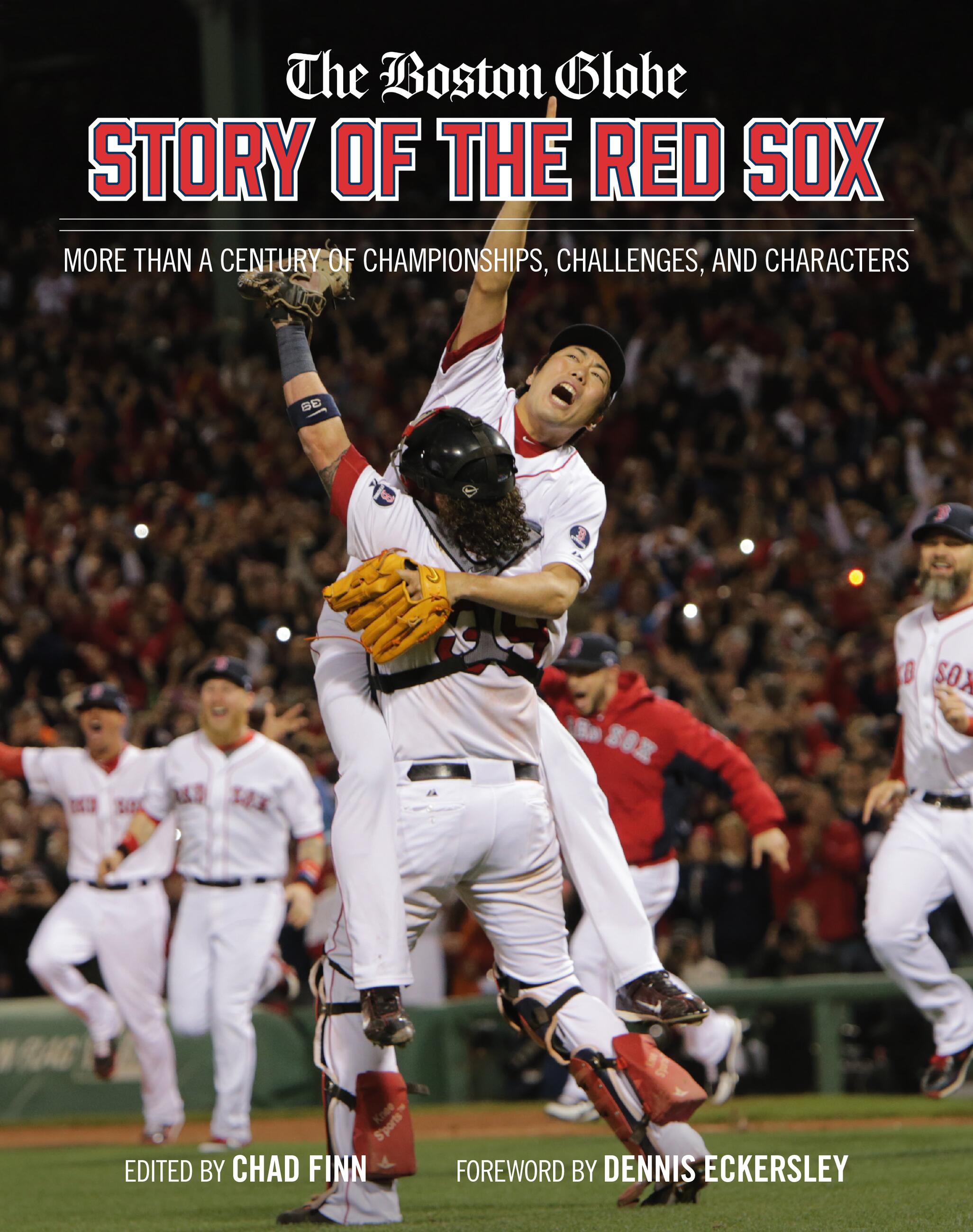

The Boston Globe Story of the Red Sox

More Than a Century of Championships, Challenges, and Characters

Contributors

By Chad Finn

Foreword by Dennis Eckersley

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Experience the illustrious and passionate history of the Boston Red Sox, one of the most storied franchises in baseball, as it happened through the articles, features, and lens of their hometown and national news outlet, The Boston Globe.

The Boston Red Sox are the most winning baseball team in the 21st century with four World Series titles, and they're not slowing down any time soon. Two of the most prominent organizations in Boston, The Boston Globe and the Boston Red Sox, combine to share a tour de force history of the heralded baseball franchise from the very beginning in 1901, when they were known as the Boston Americans.

The Boston Globe Story of the Red Sox includes more than 300 articles chronicling the team's rich history as told through the best sports writing and coverage from the beloved Globe reporters, led by veteran sports columnist and an EPPY Award finalist Chad Finn. Relive some of the biggest moments in franchise history, such as their first baseball title ever in 1901, Carlton Fisk's wave home run in 1975, David Ortiz's postseason heroics, and the most dominant Red Sox team ever in 2018.

With a foreword from beloved former Sox pitcher and broadcaster, Dennis Eckersley, and Illustrated throughout with hundreds of photographs through every era, and updated through 2022, this beautiful archive celebrates two beloved organizations, and shares the hometown story of one of the world's most popular baseball teams.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2023

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762482085

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use