Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

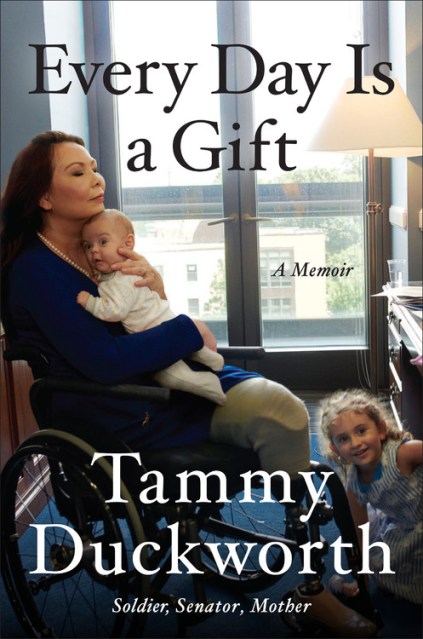

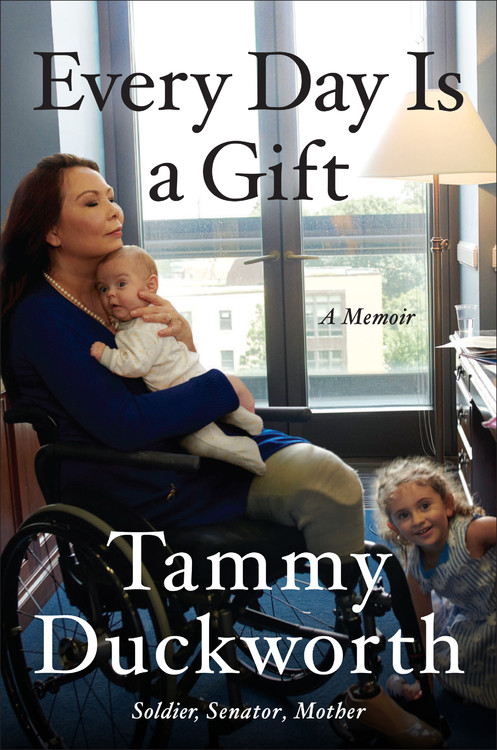

Every Day Is a Gift

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 30, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In Every Day Is a Gift, Tammy Duckworth takes readers through the amazing—and amazingly true—stories from her incomparable life. In November of 2004, an Iraqi RPG blew through the cockpit of Tammy Duckworth's U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter. The explosion, which destroyed her legs and mangled her right arm, was a turning point in her life. But as Duckworth shows in Every Day Is a Gift, that moment was just one in a lifetime of extraordinary turns.

The biracial daughter of an American father and a Thai-Chinese mother, Duckworth faced discrimination, poverty, and the horrors of war—all before the age of 16. As a child, she dodged bullets as her family fled war-torn Phnom Penh. As a teenager, she sold roses by the side of the road to save her family from hunger and homelessness in Hawaii. Through these experiences, she developed a fierce resilience that would prove invaluable in the years to come.

Duckworth joined the Army, becoming one of a handful of female helicopter pilots at the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom. She served eight months in Iraq before an insurgent's RPG shot down her helicopter, an attack that took her legs—and nearly took her life. She then spent thirteen months recovering at Walter Reed, learning to walk again on prosthetic legs and planning her return to the cockpit. But Duckworth found a new mission after meeting her state's senators, Barack Obama and Dick Durbin. After winning two terms as a U.S. Representative, she won election to the U.S. Senate in 2016. And she and her husband Bryan fulfilled another dream when she gave birth to two daughters, becoming the first sitting senator to give birth.

From childhood to motherhood and beyond, Every Day Is a Gift is the remarkable story of one of America's most dedicated public servants.

-

"Raw, unfiltered, powerful, a compelling story of courage and determination against overwhelming odds. Tammy Duckworth is a true warrior who overcame a difficult upbringing, a glass ceiling, and a horrific helicopter shootdown to become one of the most respected senators on Capitol Hill. Nothing can stop her."Adm. William H. McRaven (US Navy, Ret.), New York Times bestselling author of MAKE YOUR BED

-

"EVERY DAY IS A GIFT isn’t your usual political memoir, but it is a quintessentially American story. Tammy Duckworth’s life journey—from a difficult, peripatetic childhood in Southeast Asia though serving in the U.S. Army, House, and now the Senate—is a story of amazing grit and determination, colored throughout by a love of this country and what it stands for."Mitt Romney

-

“'Soldier, Senator, Mother'—Tammy Duckworth is all these and more. She’s a woman who overcame childhood poverty, learned to fly, fought for our country—and then created a whole new life for herself when her old one was shattered by enemy fire. The word I would use for Tammy is 'inspiration,' which is what I felt upon reading this remarkable memoir."Amy Klobuchar

-

“Tammy Duckworth’s inspiring life story reads like a novel, defined by moments of exceptional grace and resilience. As a fellow veteran, I was moved by the gripping account of her service in uniform, including the shoot-down that nearly took her life, the dramatic rescue and her harrowing 13-month recovery. She is an extraordinary leader and an exemplary American, and this book reminds us why.”Pete Buttigieg

-

“Senator Duckworth’s memoir is a compelling and engrossing narrative that invites readers into her fascinating life… Excellent work that will allow readers to get to know one of today’s most unique political voices. Readers from a wide range of backgrounds will find something to relate to in Duckworth’s story.”Library Journal (starred review)

-

“With a breezy candor that is, by turns, intimate and assertive, Duckworth offers an affecting account of a life of sacrifice, patriotism, valor, integrity, and grace.”Booklist (starred review)

-

“Heartfelt memoir from the senator and Iraq War veteran. Despite the scars of discrimination, poverty, and war, [Duckworth’s] commitment to the service of others has never wavered… An inspiring example of the power of determination.”Kirkus

- On Sale

- Mar 30, 2021

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538718506

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use