Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

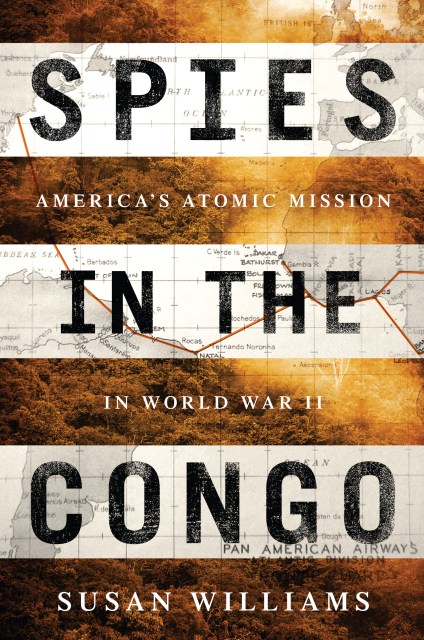

Spies in the Congo

America's Atomic Mission in World War II

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $41.00 $52.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 9, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Albert Einstein told President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 that the world’s only supply of uniquely high-quality uranium ore — the key ingredient for bomb — could be found in the Katanga province of the Belgian Congo at the Shinkolobwe Mine. Once the US Manhattan Project was committed to developing atomic weapons for the war against Germany and Japan, the rush to procure this uranium became a top priority — one deemed “vital to the welfare of the United States.”

But covertly exporting it from Africa posed a major risk: the ore had to travel via a spy-infested Angolan port or 1,500 miles by rail through the Congo, and then be shipped by boats or Pan Am Clippers to safety in the United States. It could be poached or smuggled at any point on the orders of Nazi Germany. To combat that threat, the US Office of Strategic Services sent in a team of intrepid spies, led by Wilbur Owings “Dock” Hogue, to be America’s eyes and ears and to protect its most precious and destructive cargo.

Packed with newly discovered details from American and British archives, this is the gripping, true story of the unsung heroism of a handful of good men — and one woman — in colonial Africa who risked their lives in the fight against fascism and helped deny Hitler his atomic bomb.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 9, 2016

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610396554

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use