Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

The Matriarch

Barbara Bush and the Making of an American Dynasty

Contributors

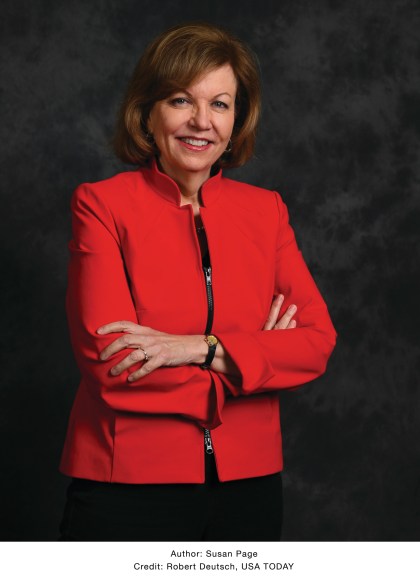

By Susan Page

Formats and Prices

Price

$37.00Price

$48.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover (Large Print) $37.00 $48.50 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $32.50 $42.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

INSTANT NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

“[The] rare biography of a public figure that’s not only beautifully written, but also shockingly revelatory.” — The Atlantic

Barbara Pierce Bush was one of the country’s most popular and powerful figures, yet her full story has never been told.

THE MATRIARCH tells the riveting tale of a woman who helped define two American presidencies and an entire political era. Written by USA TODAY’s Washington Bureau chief Susan Page, this biography is informed by more than one hundred interviews with Bush friends and family members, hours of conversation with Mrs. Bush herself in the final six months of her life, and access to her diaries that spanned decades. THE MATRIARCH examines not only her public persona but also less well-known aspects of her remarkable life.

As a girl in Rye, New York, Barbara Bush weathered criticism of her weight from her mother, barbs that left lifelong scars. As a young wife, she coped with the death of her three-year-old daughter from leukemia, a loss that changed her forever. In middle age, she grappled with depression so serious that she contemplated suicide. And as first the wife and then the mother of American presidents, she made history as the only woman to see — and advise — both her husband and son in the Oval Office.

As with many women of her era, Barbara Bush was routinely underestimated, her contributions often neither recognized nor acknowledged. But she became an astute and trusted political campaign strategist and a beloved First Lady. She invested herself deeply in expanding literacy programs in America, played a critical role in the end of the Cold War, and led the way in demonstrating love and compassion to those with HIV/AIDS. With her cooperation, this book offers Barbara Bush’s last words for history — on the evolution of her party, on the role of women, on Donald Trump, and on her family’s legacy.

Barbara Bush’s accomplishments, struggles, and contributions are many. Now, Susan Page explores them all in THE MATRIARCH, a groundbreaking book certain to cement Barbara Bush as one of the most unique and influential women in American history.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2019

- Page Count

- 592 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538715529

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use