Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

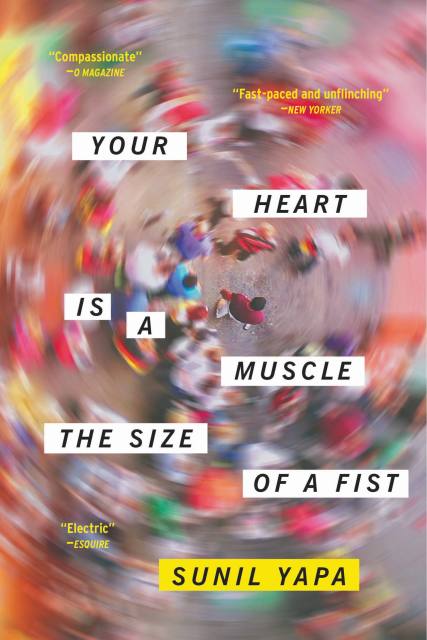

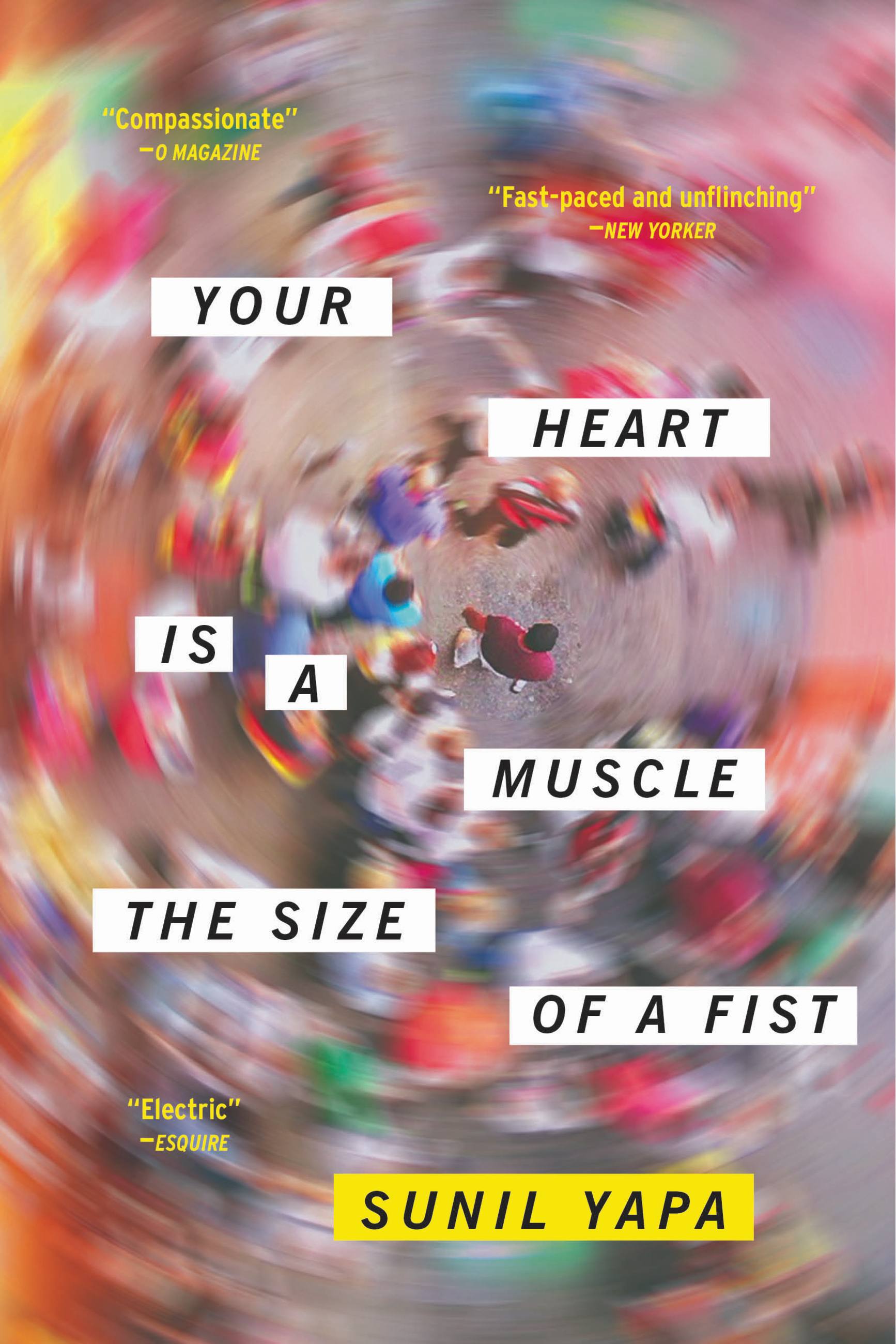

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist

Contributors

By Sunil Yapa

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 12, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This electrifying novel from an award-winning author follows a grieving father and son as they find themselves on opposite sides of a protest during an important moment in history.

Grief-stricken after his mother's death and three years of wandering the world, Victor is longing for a family and a sense of purpose. He believes he's found both when he returns home to Seattle only to be swept up in a massive protest. With young, biracial Victor on one side of the barricades and his estranged father—the white chief of police—on the opposite, the day descends into chaos, capturing in its confusion the activists, police, bystanders, and citizens from all around the world who'd arrived that day brimming with hope. By the day's end, they have all committed acts they never thought possible.

As heartbreaking as it is pulse-pounding, Yapa's virtuosic debut asks profound questions about the power of empathy in our hyper-connected modern world, and the limits of compassion, all while exploring how far we must go for family, for justice, and for love.

Grief-stricken after his mother's death and three years of wandering the world, Victor is longing for a family and a sense of purpose. He believes he's found both when he returns home to Seattle only to be swept up in a massive protest. With young, biracial Victor on one side of the barricades and his estranged father—the white chief of police—on the opposite, the day descends into chaos, capturing in its confusion the activists, police, bystanders, and citizens from all around the world who'd arrived that day brimming with hope. By the day's end, they have all committed acts they never thought possible.

As heartbreaking as it is pulse-pounding, Yapa's virtuosic debut asks profound questions about the power of empathy in our hyper-connected modern world, and the limits of compassion, all while exploring how far we must go for family, for justice, and for love.

Genre:

-

"A fantastic debut novel.... What is so enthralling about this novel is its syncopated riff of empathy as the perspective jumps around these participants--some peaceful, some violent, some determined, some incredulous... Yapa creates a fluid sense of the riot as it washes over the city. Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist ultimately does for WTO protests what Norman Mailer's Armies of the Night did for the 1967 March on the Pentagon, gathering that confrontation in competing visions of what happened and what it meant."--Ron Charles, Washington Post

"A symphony of a novel. Sunil Yapa inhabits the skins of characters vastly different to himself: a riot cop in Seattle, a punk activist, a disillusioned world traveler and a high-level diplomat, among others. Through it all Yapa showcases a raw and rare talent. This is a protest novel which finds, at its core, a deep and abiding regard for the music of what happens. In the contemporary tradition of Aleksandar Hemon and Phillipp Meyer, with echoes of Michael Ondaatje and Arundhati Roy, Yapa strives forward with a literary molotov cocktail to light up the dark."--Colum McCann, author of the National Book Award winner Let the Great World Spin

-

"Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist is visceral, horrifying, and often heroic. But above all, this book is a full-throated chorus of voices on all sides--protestors, cops, delegates, politicians, and ramblers--as democracy runs headlong into the machinery of global power. Sunil Yapa has achieved something special, a story that is as tragic as it is relevant, as unflinching as it is humane."Smith Henderson, author of Fourth of July Creek

-

"Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist is a stunningly orchestrated, symphonic work of narrative power. This novel marshals all the vital forces of our existence--from the domestic to the political--and offers them to the reader with equal doses of compassion and beauty."Dinaw Mengestu, author of All Our Names

-

"There is nothing to say about Sunil Yapa's debut novel that its wonderful title doesn't already promise--its heart beats and bleeds on every page, in prose so raw it feels built of muscle and tissue and sinew and sweat. This book is delightfully, forcefully alive, and I feel more alive for having read it."Eleanor Henderson, author of Ten Thousand Saints

-

"An open-armed love letter to humanity, this glorious novel loops around a burning center encompassing the warmth of parents and the coolness of patriarchy. Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist will compel you to look and then to witness. 'We are mad with hope' the narrator says early on, and by the end the reader is too."Tiphanie Yanique, author of Land of Love and Drowning

-

"Sunil Yapa's debut novel is possibly the most gorgeous book I've read in my entire life... Yapa's pattern of meandering, artful, full-bodied imagery, punctuated by zingy one-liners makes for a seriously addictive read... It's painful. It's gorgeous. I can't say this enough: read it."Bustle Magazine

-

"A vital, powerful read, Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist is an absorbing, multi-faceted, acutely hopeful novel."Patrick deWitt, author of Undermajordomo Minor and The Sisters Brothers

-

"A great wrenching beautiful book."Laline Paull, author of The Bees

-

"Chilling...A memorable, pulse-pounding literary experience."Publisher's Weekly

-

"[A] gripping debut...Yapa is a skilled storyteller, revealing just enough about his characters and the direction of his plot to engage his readers, yet effectively building dramatic impact by withholding certain key details. In the style of Colum McCann's Let the Great World Spin, Yapa ties together seemingly disparate characters and narratives through a charged moment in history, showing how it still affects us all in different ways."Booklist

-

"Yapa's writing is visceral and unsparing. Noteworthy, capital-I Important and a ripping read, his novel will be on many "best" lists in 2016."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"In this beautifully written, kaleidoscopically shifting novel.... Yapa penetrates to the human connections and disconnections at play between the lines of history in the era of the global village."Chicago Tribune

-

"Explosive."Entertainment Weekly

-

"If you're looking for a novel that moves with heat this winter, look no further."Flavorwire

-

"The energy and sheer humanity of Sunil Yapa's debut will grab you, wrap you in, and won't let you go-and that's just the start of why you're going to love this. Seven characters narrate this charged book, which centers on a protest. It's so layered, you'll finish this wondering how Yapa pulled off what he did."Bustle

-

"It's not often that a novel takes a fraught event from the recent past, one that most of us only experienced in the flash of the cable news cycle or the static of print headlines, and imbues it with so much heart and soul that we do something we almost never do in the constant crush forward and faster-we pause and reconsider. That is the power of literature. Sunil Yapa's Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist does just this for the momentous protests of the 1999 World Trade Organization's (WTO).... Yapa does a heroic job of journeying into the heart of this complex set of events, illustrating how they grow out of and impact the character's lives. And while the heart may be the size of a fist, here it paradoxically seems to encompass the whole world and all of its citizens, who pulse with its every beat."The Rumpus

-

"[A] gripping, profoundly humane first novel.... An absolutely compelling read."Bookpage

-

"Yapa's novel is a much-needed and refreshing pivot point. His novel makes a case for the validity of all opinions in a conflict the better part of two decades old. This rare quality of his work is a practice that many could benefit from in current conflicts, foreign and domestic."Denver Post

-

"Sunil Yapa's voice and ambition leap off the page. Here is a writer to watch."Minneapolis Star Tribune

-

"This furiously paced and contrapuntal literary tour-de-force makes use of multiple vantage points and benefits from a remarkably empathic sensibility on the part of its author.... With Yapa burrowing into the hearts of these characters, each distinct yet sufferers all, his already weighty story attains a level of profundity."Miami Herald

-

"Like magic, Yapa uses this handful of perspectives to create snapshots that allow the reader to imagine who else was there that day and what they were doing, thinking, and feeling...I can't imagine a better book to have kicked off my year in reading."Bookriot

-

"Fast-paced and unflinching.... As these characters encounter one another in a fog of tear gas and pepper spray, Yapa vividly evokes rage and compassion. Underlying the novel, and at once reinforced and rejected, is the chief's mantra: "Care too much and the world will kill you cold."Dallas Morning News

-

"Yapa's melding of fact and fiction, human frailty and geopolitics, is a genuine tour-de-force, and an exciting literary debut."Seattle Times

-

"Fast-paced and unflinching.... As these characters encounter one another in a fog of tear gas and pepper spray, Yapa vividly evokes rage and compassion. Underlying the novel, and at once reinforced and rejected, is the chief's mantra: "Care too much and the world will kill you cold."New Yorker

-

"A beautifully written book."Entertainment Weekly

-

"An achingly compassionate fiction debut."O Magazine

-

"As electric a novel as I've ever read."Benjamin Percy, Esquire

- On Sale

- Jan 12, 2016

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Lee Boudreaux Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316386524

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use