Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

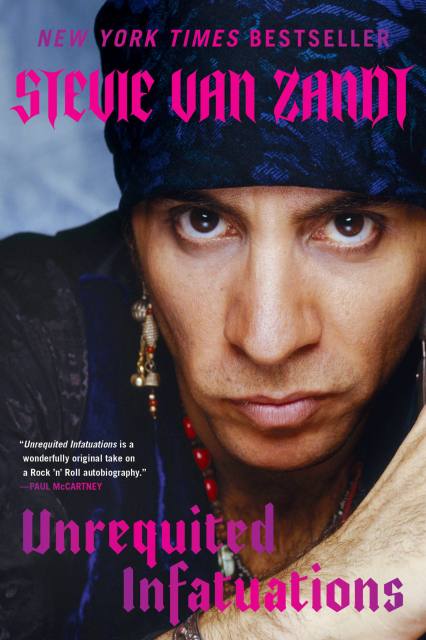

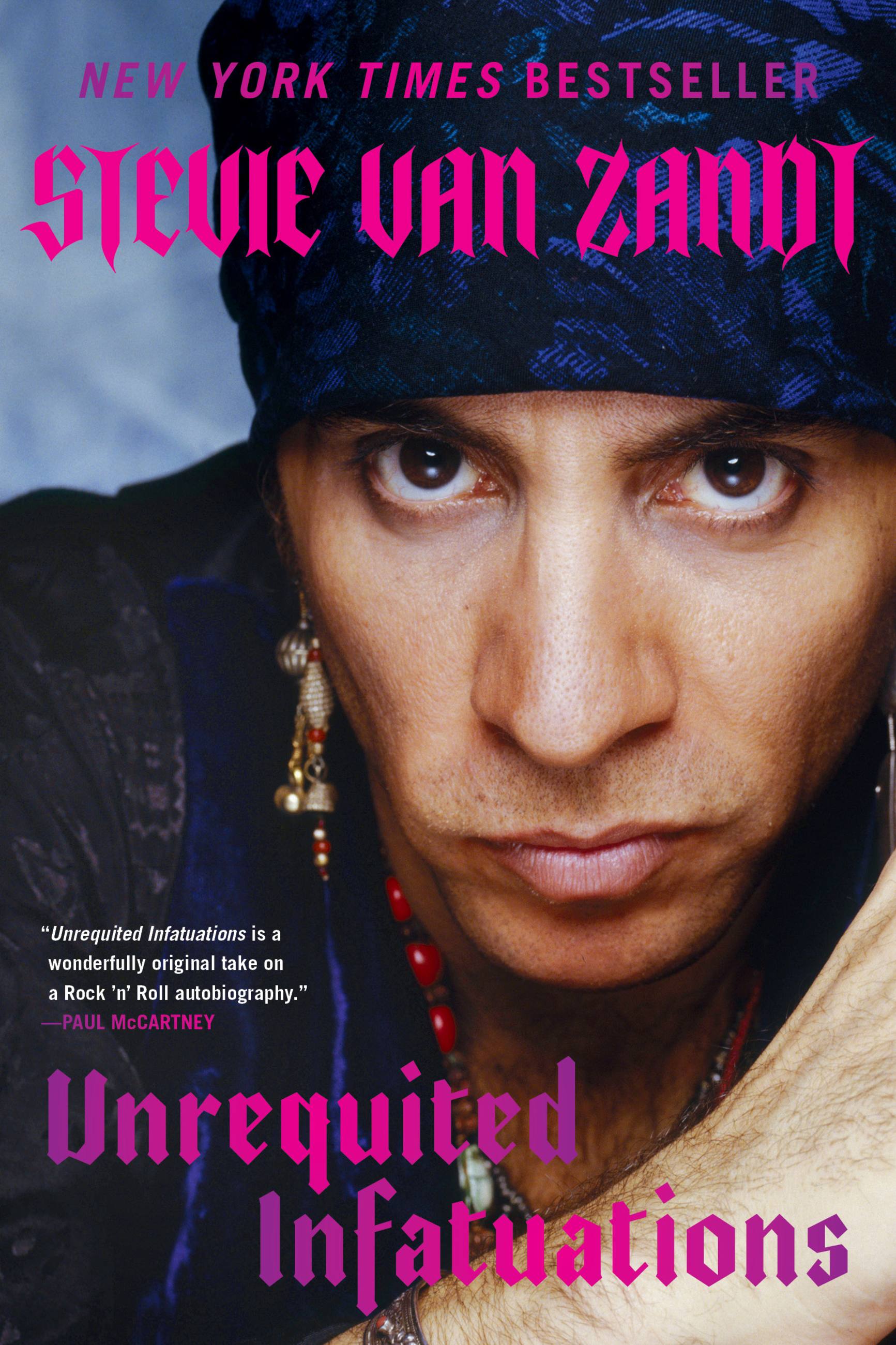

Unrequited Infatuations

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Hardcover $31.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 27, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Uncover never-before-told stories in this epic tale of self-discovery by a Rock ’n’ Roll legend, member of the E Street Band, and subject of the acclaimed HBO documentary Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple

What story begins in a bedroom in suburban New Jersey in the early ’60s, unfolds on some of the country’s largest stages, and then ranges across the globe, demonstrating over and over again how Rock and Roll has the power to change the world for the better? This story.

The first true heartbeat of Unrequited Infatuations is the moment when Stevie Van Zandt trades in his devotion to the Baptist religion for an obsession with Rock and Roll. Groups like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones created new ideas of community, creative risk, and principled rebellion. They changed him forever. While still a teenager, he met Bruce Springsteen, a like-minded outcast/true believer who became one of his most important friends and bandmates. As Miami Steve, Van Zandt anchored the E Street Band as they conquered the Rock and Roll world.

And then, in the early ’80s, Van Zandt stepped away from E Street to embark on his own odyssey. He refashioned himself as Little Steven, a political songwriter and performer, fell in love with Maureen Santoro who greatly expanded his artistic palette, and visited the world’s hot spots as an artist/journalist to not just better understand them, but to help change them. Most famously, he masterminded the recording of “Sun City,” an anti-apartheid anthem that sped the demise of South Africa’s institutionalized racism and helped get Nelson Mandela out of prison.

By the ’90s, Van Zandt had lived at least two lives—one as a mainstream rocker, one as a hardcore activist. It was time for a third. David Chase invited Van Zandt to be a part of his new television show, the Sopranos—as Silvio Dante, he was the unconditionally loyal consiglieri who sat at the right hand of Tony Soprano (a relationship that oddly mirrored his real-life relationship with Bruce Springsteen).

Underlying all of Van Zandt’s various incarnations was a devotion to preserving the centrality of the arts, especially the endangered species of Rock. In the twenty-first century, Van Zandt founded a groundbreaking radio show (Little Steven’s Underground Garage), created the first two 24/7 branded music channels on SiriusXM (Underground Garage and Outlaw Country), started a fiercely independent record label (Wicked Cool), and developed a curriculum to teach students of all ages through the medium of music history. He also rejoined the E Street Band for what has now been a twenty-year victory lap.

Unrequited Infatuations chronicles the twists and turns of Stevie Van Zandt’s always surprising life. It is more than just the testimony of a globe-trotting nomad, more than the story of a groundbreaking activist, more than the odyssey of a spiritual seeker, and more than a master class in rock and roll (not to mention a dozen other crafts). It’s the best book of its kind because it’s the only book of its kind.

**Instant International Bestseller, New York Times Bestseller, USA Today Bestseller, Wall Street Journal Bestseller, Los Angeles Times Bestseller, Publishers Weekly Bestseller**

-

“Unrequited Infatuations is a wonderfully original take on a Rock ’n’ Roll autobiography.”Paul McCartney

-

“In the New Jersey state of mind somewhere between Bruce Springsteen Stadium and The Bon Jovi Arena is a little known street called Little Steven Boulevard with hundreds of endless souvenir shops, gift stores all associated with Little Steven the Consigliere, all top level stuff, the gangster memorabilia, Little Steven wallets and handbags, bandanas and head scarfs, Little Steven glassware and coffee mugs, Little Steven flags, key chains, stickers and patches, pens and guitar picks, cardboard stand-up cut outs of Little Steven, jigsaw puzzles and buttons. You can spend a fortune on the street, listen to every song he ever played on and watch every television show that he’s made, visit the underground garage and also enroll in the Little Stevie’s underground college. It’s all there, a lot of copies of this book as well. And just like one of Stevie’s favorite songs, this book keeps you hanging on and checks all the boxes (check out the one on page 153—it’s hilarious and there’s hundreds of others).Bob Dylan

This indeed is a cautionary tale filled with outrageous humor, worldly wisdom, and an uncanny sense of daring. No doubt about it, Stevie proves it time and time again he’s the man to know.” -

“An inimitable Rock ’n’ Roll life told as boldly as it was lived. From the stages of the biggest stadiums in the world to the politically roiling provinces of South Africa, my good friend pursued his Rock ’n’ Roll vision with a commitment few have displayed. A must read for E Street Band fans and Rock fans the world over. In this book Little Steven LETS IT ROCK!”Bruce Springsteen

-

“What a wonderful, witty, incisive, moving, authentic, and beautifully written memoir. Stevie Van Zandt’s Unrequited Infatuations is a heartfelt and soulful tour though Rock ’n’ Roll history, politics, and pop culture from the vantage point of a rare talent and singular American life. I loved every page.”Harlan Coben, bestselling author of Win, The Boy from the Woods, Run Away, and the Myron Bolitar series

-

“A glorious trip into the mind of a true Rock and roll Renaissance Man. Stevie’s autobiography digs beneath the surface of his music, evolving into something extraordinarily rich and complex. It’s part Rock ’n’ Roll history lesson, part political thriller, part revelatory dive into the brotherhood of a band. And so much more. What’s most impressive is Stevie’s self-deprecating honesty. He has the courage to write about his failures, alongside tales of his enormous success. The stories are also wildly entertaining, hilarious and emotionally devastating. One of the best Rock ’n’ Roll books ever written. It belongs on a shelf between Bob Dylan’s Chronicles and Gerri Hershey’s Nowhere To Run. A masterpiece.”Chris Columbus, director, producer, and screenwriter

-

“Steven and I grew up in the same town, two miles apart—unless you count the fact that creatively, he was on another planet. Beneath the bandana is the beautiful mind of a polymath: singer, songwriter, actor, activist, arranger, thinker, and creator. There is sex, there are drugs, and thank the Lord—there is rock and roll. Names are named. Mistakes are made. Fights are (mostly) forgiven. And lightning strikes more than once. This is the beautifully told story of a great American life, and I dreaded the arrival of the final page.”Brian Williams, journalist

-

“I was expecting a great music book with a bit more depth than most. What I got was the Tao Te Ching of Rock biographies! Only it’s Lao Tzu with a fabulous sense of humor! This adventure is metaphysically amazing.”Michael Des Barres, actor / writer / musician / DJ

-

“Steven Van Zandt is the ultimate Rock ’n’ Roll soldier, an eyewitness to history who has made plenty of his own in the trenches and the studio. His stories of struggle and awakening, the mysteries of creation, and the ties that bind in every great band come at you like a blaze of killer 45s in a true voice of America: part Vegas, part Alan Freed, all New Jersey.”David Fricke, journalist, SiriusXM, Mojo, Rolling Stone

-

“Unrequited Infatuations is as musical, soulful, funny, adventurous, inspiring, and real as the man who wrote it, the one and only Stevie Van Zandt."Jon Landau, journalist, music producer, and manager

-

“If this book was a song, you’d want to crank up the volume. It’s one of the best rock memoirs ever. It’s got soul, it’s got humor, it’s got some tough truths and some wild stories all wrapped up in battle scars and telling memories you’d usually need a backstage pass to catch. Most of all—as the gentlemen vocalists of another era would say—it’s a gasser. It’s so much fun you can dance to it.”Jay Cocks, film critic and screenwriter

-

“A pleasure for music fans and one of the best entertainment memoirs in recent years."Kirkus Reviews

-

“Stands head and shoulders above the many celebrity memoirs out there.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Steven Van Zandt believes in the power of rock 'n' roll. He lives it, breathes it, brings it to life on the stage, and, with his new memoir, Unrequited Infatuations, magnificently on the page….[The book] is rife with the highs and lows, joys and conundrums that have marked his progress to rock's loftiest plateaus and life's most crushing ebbs. But Van Zandt's story is also about having the courage to take logic-defying, outrageous risks….As [his] story powerfully demonstrates, the musician discovered the essence of his life's passion in the moment when he gave up everything….As with the best and most honest of life stories, Unrequited Infatuations reminds us that it's the getting there that matters.”Salon

-

“[Van Zandt’s] florid voice translates well to the page. The result is a delightful memoir that is a whole lotta wild fun. All in all, this book is utterly true to who Van Zandt is.”Air Mail

-

“[Van Zandt’s] new memoir illustrates just how seminal he’s been in the past five decades of American popular music. An anti-apartheid activist who wrote the protest song “Sun City,” he’s spent years celebrating and advocating for rock ’n’ roll as an art form: He hosts a weekly syndicated radio show focused on garage rock, created two music channels on SiriusXM, founded an indie record label, and even helped develop an arts education initiative that incorporates music history — from classical to reggae — into K-12 curricula. While some rock stars hide behind a veil of detached coolness, Van Zandt is a man marked by genuine enthusiasm, and his memoir reads like a love letter to the people and places and music that made him, with a healthy dose of nostalgia and good-natured humor.”AARP, “9 New Music Memoirs and Biographies for Rock and Blues Fans”

-

"A rollicking read."USA Today

-

“One of the best musician’s memoirs I’ve ever read.”Alan Paul, Wall Street Journal Contributor

-

“In his fantastic memoir, Unrequited Infatuations, Van Zandt digs into both of those worlds – as a musician and actor – each with compelling backstage stories and refreshing frankness… Van Zandt’s humor and humility is evident throughout the book, speaking nonchalantly and often in self-deprecating ways about his role and impact on some of biggest pop and art cultural moments in modern memory.”Glide Magazine

-

"[UNREQUITED INFATUATIONS is] a highly entertaining and rollicking memoir.”Houston Press

-

“This thing bounces on the page, from the E Street Band to The Sopranos to Sun City, with a discursive glee. He reads like the Last American Beat.”Chicago Triibune

-

“The book is an insightful look at the creative process…[and] recounts his extraordinary journey from playing guitar in Springsteen’s E Street Band to playing gangster Silvio Dante in the classic HBO series The Sopranos, as well as his work as a writer, activist and arts advocate.”Wall Street Journal

-

“E Street Band fanatics, take note: Little Steven has written a memoir chock-full of previously untold stories about his Baptist upbringing, joining forces with Bruce Springsteen, recording Sun City and becoming a political activist, acting on The Sopranos and more.”CNN Underscored

-

“Van Zandt’s unique memoir…combines his expansive knowledge of music creation with his personal development in the sociopolitical sphere…[His] bravado shines through his prose, and he’s refreshingly honest as he takes readers through his many professional disappointments. Sprinkled throughout are a truly impressive history of rock and roll and entertaining digressions about famous friends in the music and film industry that will appeal to all readers….Van Zandt is front and center in this wild, fun memoir.”Booklist

- On Sale

- Sep 27, 2022

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306925436

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use